They can really hold their head up!

;-)

There’s a special intuitive connection certain musicians share that cannot be qualified in technical terms, but can instead be described as being both magical and mysterious. Case in point: the 60-years-and-counting musical mindmeld between lead vocalist Colin Blunstone and keyboardist/vocalist Rod Argent, the twin driving forces behind British invasion stalwarts The Zombies. “Rod said he grew up learning to write songs for my voice, and I learned to sing professionally singing his songs,” Blunstone confirms. “So, there is something magical about his songs, and me singing his songs.”

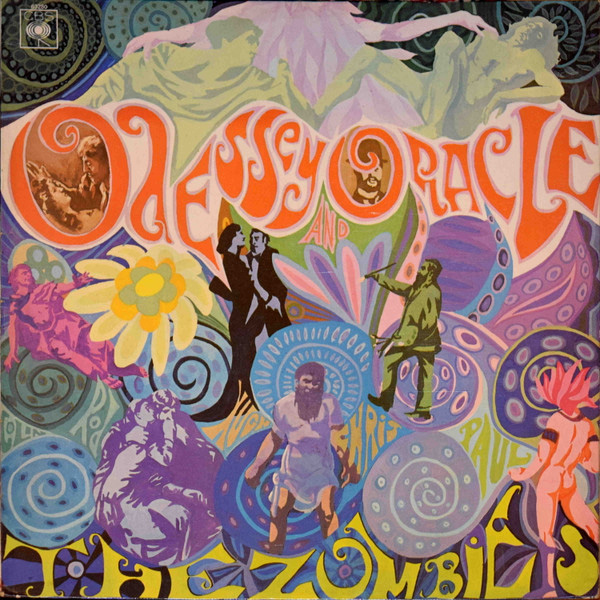

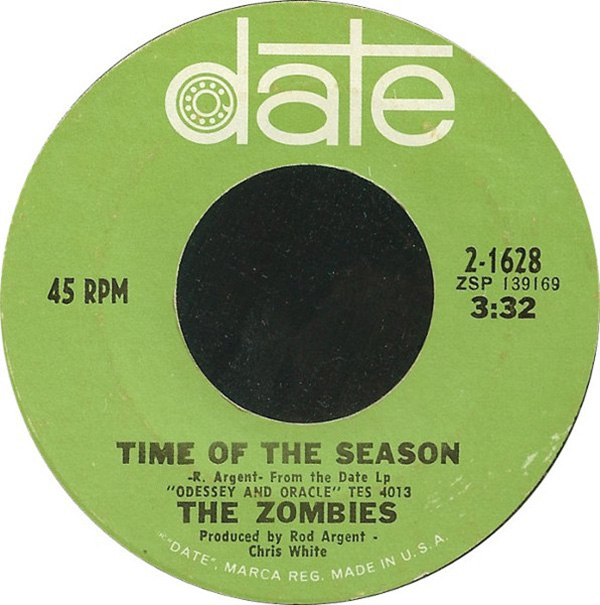

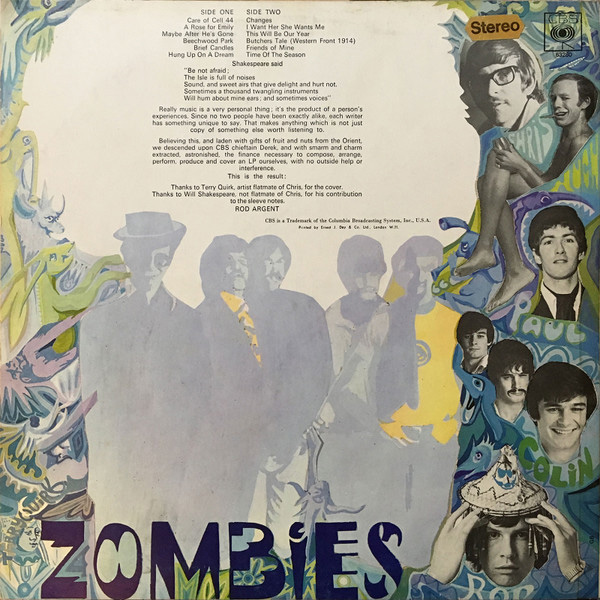

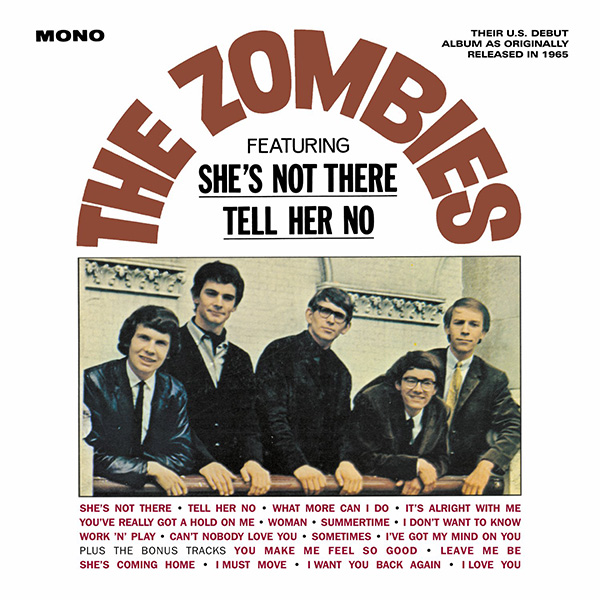

Known for impeccably layered harmonies and permanent earworm hits of the 1960s like “Tell Her No,” “She’s Not There,” and “Time of the Season” — not to mention April 1968’s Odessey and Oracle, the career-defining album that in one sense got away, but in another ultimately became legendary for am engaging mono mix best enjoyed on vinyl — The Zombies, much like their namesakes, have had quite the recurring bouts with mortality and resurrection. (Sidenote: The misspelling of the word Odessey on that album’s cover is quite well-documented elsewhere, so we won’t be going down that artistic/linguistic rabbithole here.)

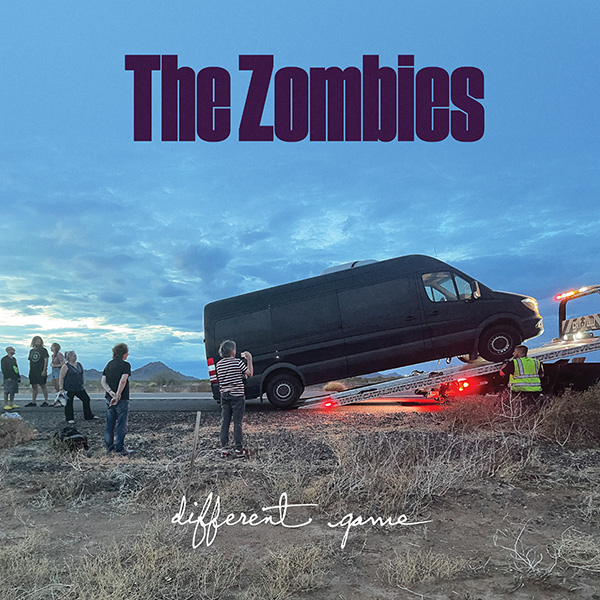

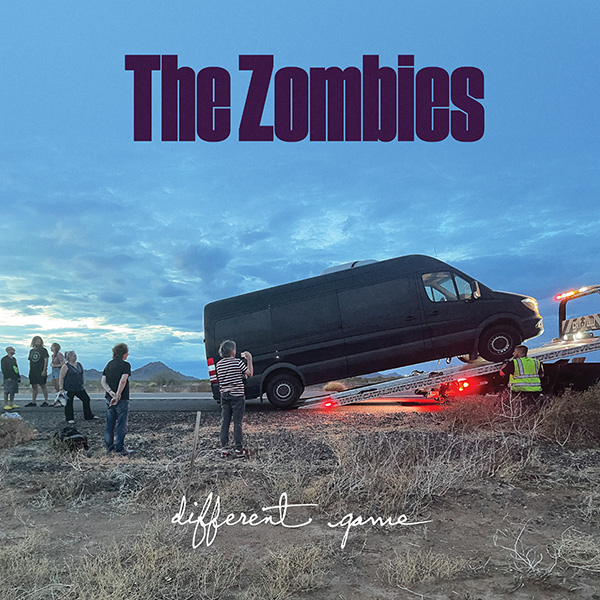

Still going strong today, The Zombies are on the precipice of the imminent release of their seventh studio album, Different Game, which comes out in fine 1LP form on March 31 via Cooking Vinyl. Produced by Rod Argent together with the band’s longtime live audio engineer Dale Hanson, Game is available in both standard black vinyl ($29.99 SRP) and in limited-edition red ($35 SRP), the latter being an exclusive to The Zombies official store. (All relevant pressing stats will be forthcoming once they’re properly confirmed.) To be sure, Game contains all the hallmarks of a classic Zombies LP, from the finely layered harmonies on “Rediscover” to the fully careening “Merry-Go-Round” to the impassioned harmonica breaks on “Got to Move On.”

“I think the arrangements on Different Game are wonderful,” Blunstone admits. “When Rod writes a song, a lot of the arrangement will be in the writing of the song. He very often knows what he wants the bass lines to be. He may even know what he wants the drum pattern to be.”

Indeed, the Blunstone-Argent creative axis remains quite palpable. “There is a very subtle feeling between us when we record,” the vocalist continues. “With just a look, we can encourage one another, support one another, and drive one another on. It’s very nuanced and subtle, but it’s the result of having gone through our formative years together and him learning how to write, and me learning how to sing. It’s been a long road, and I think we can still lift one another in just a look.”

Blunstone hopes their collaboration continues as indefinitely as humanly possible. “Rod and I have always said we wanna keep touring, writing, and recording for as long as we’re physically able,” he asserts. “Hopefully, we’ll go on for some time yet, though we are aware we probably don’t have forever. We are very much in the autumn of our careers at the moment.” Based on what I’m hearing on Different Game, the time of The Zombies’ autumn season is still going strong.

Blunstone, 77, and I got on Zoom together a few weeks ago to discuss the connective sonic tissue between Different Game and Odessey and Oracle, why he prefers hearing songs like “Time of the Season” in mono, and why the Odessey album benefitted from some things The Beatles left behind in EMI Studios while they were recording their legendary June 1967 Sgt. Pepper album. Tell it to me slowly (Tell you what?) / I really want to know . . .

Mike Mettler: I feel like some of the harmonies on Different Game tracks like “Rediscover” hearken back to a Beach Boys vocal-stacking influence. After I first heard “Rediscover,” I went back to the Odessey and Oracle song “Care of Cell 44,” and I played them back-to-back. I felt like they were bookends in a way, though I don’t know if you intended that to be the case.

Colin Blunstone: Well, they could be, because The Zombies have always been a band, whether it be the first incarnation or the second incarnation, that do put great emphasis on harmony — both recorded harmony, and when we play live.

That actual piece you are referring to at the beginning of “Rediscover” may have been influenced by the fact that we spent about six weeks on the road with Brian Wilson and his band [in 2019]. In no way is it being copied, but it might’ve just triggered something — and it was great fun doing it. The guys in our band are just great harmony singers.

Mettler: I want to ask you more about those Zombies harmonies in a moment. But I think it’s worth noting first that a lot of the pop and rock music of the early-’60s era was based more on vocal-and-guitar interaction, whereas it’s mainly about how keyboards and vocals interact in The Zombies. Is that fair to say?

Blunstone: Well, absolutely! Right from the beginning, it was a little bit different in that this is a keyboard-based band that features three-part harmonies. We just did that naturally. There wasn’t a contrived effort to be different. It’s just the makeup of the band, really.

Rod is such an incredible keyboard player, and he’s the cornerstone of the band. The band is built around him. He’s also a very good harmony singer, so he could help me and [bassist/background vocalist] Chris White when we were getting our harmonies together.

A lot of people have asked me about The Zombies’ harmonies, and it’s quite hard to work out what the harmonies are, because they’re not standard harmonies. They came about because I was a very unsophisticated singer. When block harmony was coming up [in a song], they would always ask me to sing what I thought the melody was, so I would sing that. And very often, when it would come to a chorus, I would take a high harmony, and they would make sure I’d already got that in my mind so I was all set for what I’d sing.

Then Rod would try and get Chris [White] a very simple harmony, because he has to play bass and sing that harmony, which was sometimes quite close to one note — and then Rod would fill in all the holes in the harmony. Rod could sometimes get a very challenging part because of the way we put it together, but it’s not the way most people do harmonies, you know?

Mettler: From your point of view, is there one perfect example from the 1960s where you can say, “We did it our way” — as in, this is the best version of our three-part harmony? Do you have a track that stands out like that?

Blunstone: Just off the top of my head, “She’s Not There” [released in 1964] has got three-part harmony. If you take that three-part harmony away — when I’ve sung with other bands where they don’t bother with the harmony, the song certainly loses something. It really needs that three-part harmony.

Mettler: Can’t argue with you about that. Moving ahead just a bit, most of Odessey and Oracle [released in April 1968 on CBS in the UK, and Date in the U.S.] was done at EMI Studios in London, but not all of the album was cut there.

Blunstone: Oh, yeah, most of it was recorded there, but there was a little bit that was recorded at Olympic Studios in Barnes [a district in south London]. That studio was famous because, for a time, The [Rolling] Stones recorded there. It’s sad that the studio’s not there anymore. I think it’s a picture house now — a movie theater.

Mettler: When you knew Odessey and Oracle was going to be an album you’d have better sonic control over, did you and Rod and the engineers ever have a discussion of like, “This is how we want this material to sound”? Was there a template of what and how you wanted to record, now that you had a couple years in a recording studio under your belt?

Blunstone: Well, I would say Rod Argent and Chris White were in the production seats, really, and they were aided by such incredible engineers there. Peter Vince and Geoff Emerick were the two engineers who worked on Odessey, and I just wish we’d worked with them before that. I’ve never actually said that before! But I do wish we could’ve worked with them before, because I think our records could have turned out quite different.

Mettler: Odessey and Oracle constantly reveals itself to me as a template of how you were on point while you were recording it in 1967, in terms of where the sound was coming from, and where it was going, in that year. You were right where The Beatles cut Sgt. Pepper and where Pink Floyd’s The Piper at the Gates of Dawn was being created in the same place at EMI Studios on Abbey Road. Did you guys cross paths with anybody from either of those bands while you were in the studio?

Blunstone: Do you know, I don’t remember meeting any other artists there. It sounds a strange thing to say, but we just missed The Beatles. They finished Sgt. Pepper about three days before we started Odessey and Oracle [on June 1, 1967], although they were mostly in Studio Two. They always recorded in Studio Two — well, occasionally in Studio Three, and that’s where we recorded Odessey and Oracle.

When we went in there, a lot of their instruments were scattered around — percussion instruments, tambourines, and so forth — they were scattered around on the floor, so we were thrilled to pick those up and use them!

In particular, John Lennon’s Mellotron had been left behind. And Rod, as he always says, jumped on that. If you listen to Odessey and Oracle, Mellotron is all over it. But if John Lennon hadn’t left his Mellotron behind, the album would’ve sound very different.

Mettler: The Mellotron can be a difficult instrument for people to wrap their heads around, but the sound it makes really fits the Odessey record, especially given what we heard of its use on records by King Crimson and The Moody Blues. Now, while you’re singing for Odessey, was there one early moment or song where you knew, “Okay, we’re finally getting what I hear in my head”?

Blunstone: Well, I thought we were onto something special when we were recording “Care of Cell 44,” which, to me, even now, sounds the most commercial track on the album. It shows you what I know because it was released as a single, and it wasn’t a success. (chuckles)

But for me, it sounds so commercial! I love the lyric because it’s quite a sad lyric, but it’s paired with a really jaunty melody. If you don’t really listen to the lyric, you might miss what that song’s about — but it’s such an unusual topic.

Mettler: You’re so right about that. Well, to put the button on Odessey, even today, that record still is near or at the top of people’s lists of favorite albums. Why do you think it still connects like that? Is there some magical sonic elixir in there that people will always connect with, especially on vinyl?

Blunstone: Well, I think probably there is. First and foremost, it’s a collection of wonderful songs — every track. I didn’t write any of them, so I can judge it as an outsider, you know? And I think every track is just breathtaking.

It was recorded extremely well by Peter Vince and Geoff Emerick in Abbey Road, which helps make it into a timeless classic. That’s why people still listen to it, even though it wasn’t very successful at the time, and it led to the band breaking up.

Also, there are some great performances on there. Because Abbey Road is so expensive — it was then, and it is now — we had a very small recording budget, so we rehearsed really extensively before we recorded there. We knew when we went into the studio exactly what songs we were gonna record, and what keys they were in. We knew the arrangements. We were just looking for a performance, so we recorded really fast — and we were just lucky to have those wonderful engineers who could help us to do that.

Mettler: Obviously, “Time of the Season” is another three-part harmony track that many people zero in on when they think about the Odessey album. I know it took a good while for you guys to put that one together, but did you have a sense that “Time of the Season” was gonna basically become a timeless song, or could you not feel about it in that way in the moment?

Blunstone: Well, Rod always felt it was a strong song, and could be a big hit. I must admit (chuckles), I didn’t! I should never be an A&R man, because I can’t pick singles at all. But, no, I didn’t see that one. I thought it was an “okay” track. But “Care of Cell 44,” “Hung Up on a Dream,” “A Rose for Emily” — those are some of the other ones on there I thought were really, really special.

Mettler: “A Rose for Emily” is quite special, I agree. One other thing I wanted to ask about “Time of the Season.” There’s a point in it with that lower vocal inflection on the single word “show” the comes before the full phrase, “To show you what you need to live.” How did that come about?

Blunstone: You mean the way those vocal harmonies are layered? I’ll tell you what I think that is. The Beatles had been in just before us, and they were very conscious of Pet Sounds [The Beach Boys’ aforementioned groundbreaking May 1966 LP]. Pet Sounds had been recorded on an eight-track machine. John Lennon said to the engineers — that’s an American word, but we’d probably say boffins (laughs) — but they had a scientist department at Abbey Road that used to mend all the machines, and all that stuff.

Mettler: Right, the labcoat guys.

Blunstone: Yeah, the labcoat guys — and they were in long white coats, these guys. And John Lennon said to them, “We want eight tracks.” They said, “We can’t give you eight tracks. There are no eight-track machines in the country!” And there weren’t, but what they managed to do was to get two four-track machines to play together. In the process, you lost one track, so you actually got seven tracks.

Well, because The Beatles had been using that equipment just before us, it meant that when we went in there, for the first time, we were recording on more than four tracks. So, when we recorded, it gave us the scope to add things.

What you’re talking about is the sort of thing that was added — mostly by Rod. The thing I remember is Rod just saying, “I can hear it, that part. Shall I have a go?” And I think Hugh, our drummer, said, “Yeah, go and do it.” It was one take. It took, whatever, three minutes and something, and he just went through it and did that bit — and, of course, it’s so much part of the song!

I think he added the little bass melody that you’re thinking about as well — well, I know he did. He was able to do that. I mean, Rod could always hear things like that, but he was able to do it because we had these added tracks, and that was because The Beatles put the pressure on the lab department at Abbey Road.

Mettler: The Zombies had recorded mostly in mono up to and including Odessey. Didn’t the label people tell you, “We also need a stereo version of this record”? You had intended it to be mono, and then you got told they needed it in stereo too. Do I have that correct?

Blunstone: Yes. Right at the end. We’d recorded the album mono, and we’d used up our recording budget, which was minuscule. And then they told us, “Well, we need a stereo version of this.” And so, Rod and Chris paid for it — the extra time in the studio, themselves — and made a stereo mix as best they could.

Mettler: Did you care whether something was in mono or stereo? Do you have a preference, either as a listener or a singer?

Blunstone: Well, I think if it’s recorded in mono, it will always sound better in mono — and that’s certainly true of Odessey and Oracle.

Mettler: Yeah, I agree. Especially for “Time of the Season,” the mono version is the one I actually prefer, especially how you have the “ahhhh!”s placed on it, which just feels right to me.

Blunstone: Oh yeah! I’m not sure how successful the stereo mix was, to be absolutely honest. I mean, it was done on a shoestring — and, of course, it was the very beginning of that technology. So, it is what it is, you know?

Mettler: It sure is. Now, if I remember it correctly, the way you guys had to record “She’s Not There” in 1964 — which is basically your first studio session ever, at Decca Studios in London — you had to kick your first engineer out because he just wasn’t cutting it, right?

Blunstone: We did.

Mettler: What happened there?

Blunstone: Well, the trouble was, we’d been booked in for the evening session. In those days, it was to be quite stimulating and maybe a bit romanticized to work through the night. It was booked for us for 7 o’clock. When we arrived there, unfortunately, our engineer — who was a very good engineer, and he’d worked on many a hit record — he’d been at a wedding all day, and he was absolutely, completely drunk. On top of that, he was very, very aggressive.

I can remember we were trying to sing with the headphones on, and this guy was screaming through the headphones — things like profanities, and threats. After about 20 minutes in the studio, I thought, “I don’t think this is for me. I really don’t.” But now I have to laugh while I’m thinking about it, because here I am, 60 years later, still in the music business! (laughs)

But we had a bit of luck, and then he passed out. He went out cold, and we carried him out of the studio — one Zombie on each leg, and one Zombie on each arm — up two flights of stairs, and into a black London taxi. We waved him goodbye, and we never saw him again — ever.

His assistant took over. It was a guy called Gus Dudgeon. That was Gus’s first session ever, and it was our first session ever. I know he is no longer with us [Dudgeon passed away in July 2002], but he would always say, whenever we’d meet up, “You know, that was my first session. I remember it!” He produced all those wonderful Elton John albums, and David Bowie, and many others. He was probably the most successful producer in the world for a time, you know?

Mettler: He sure was. During that very first session with Gus and producer Ken Jones, were you guys just working off instinct as to how you put your harmonies together?

Blunstone: Yeah. And remember, when we recorded “She’s Not There,” Rod and I were 18, and Paul Atkinson, who was the guitarist, was 17. [Drummer] Hugh Grandy was 18 as well, I think, and [bassist] Chris White was a couple of years older.

I’m sure we’d rehearsed this song well, even though it had only been written probably a couple of weeks before the session. It was quite by chance — we’d won a big rock & roll competition, which led to a contract with Decca. We’d been introduced to a producer called Ken Jones, and he was sort of giving us a pep talk. He was saying, “You could always write something for this album,” but then he moved on to something else, and he didn’t make a big thing of it. I listened to the whole thing he said, but I didn’t take him seriously about us writing something. But Rod and Chris did, and they came back a few days later and played us two songs: “She’s Not There,” and “You Make Me Feel Good,” which went on to be the B-side.

I think we all knew “She’s Not There” was a special song. And in that first session, we recorded “She’s Not There,” “You Make Me Feel Good,” and a jazz waltz version of [George] Gershwin’s “Summertime,” which is just great. I think “She’s Not There” may have either been Rod’s second or third song, because there was another song on the session that was called “It’s Alright.”

We recorded four songs very, very quickly, and we were never allowed into the mixing sessions. That was done separately. With Ken Jones producing us, we were never allowed into the mixing, and that’s one of the reasons why we eventually left Ken Jones.

And, with that, we also left Decca, because all the guys wanted to record at least one album where our songs were heard in the way they’re meant to be heard, you know? And that’s why we recorded Odessey and Oracle the way we did.

Mettler: I want to close with a very cosmic question for you, if you don’t mind. I want to project us 50 years into the future so it’s 2073, and unless there’s some weird science stuff going on, I doubt you and I will physically be on the planet at that point. However people listen to music in that year and they type in either “Colin Blunstone” or “The Zombies,” what would you want them to get out of that experience?

Blunstone: Well, I’d like — (slight pause) I’m trying to think what the expression is. I’d like it to lift their spirits. I think that says it really well, actually. I’d like them to be excited, thrilled, moved, sad — yeah. Whatever kind of song it is, I’d like them to feel something. And I think they will, because, you know, “She’s Not There” was recorded how many years ago — 59 years ago, almost 60? I still think that’s as fresh and as relevant today as it was when it was recorded.

I hope the tracks we’re recording now will be received the same — and I would like to think they will. When they listen to The Zombies tracks, I’d like to think that will lift their spirits and they will get something from it, be it happiness, or a little sadness — but it will be some kind of emotional response.

THE ZOMBIES

DIFFERENT GAME

1LP (Cooking Vinyl)

Side 1

1. Different Game

2. Dropped Reeling & Stupid

3. Rediscover

4. Runaway

5. You Could Be My Love

Side 2

1. Merry-Go-Round

2. Love You While I Can

3. I Want To Fly

4. Got To Move On

5. The Sun Will Rise Again

They can really hold their head up!

;-)

This article is an in-depth look at the musical harmony between Colin Blunstone and Rod Argent of The Zombies. It was fascinating to read about their intuitive connection and how they continued to create magic together for over 60 years. My word finder team and I were all excited to check out their new album, Different Games, and hear the hallmarks of a classic Zombies LP.

It really shouldn't be necessary to explain the cassette "trend" notion. Though some of the naysayers prefer to be Debbie downers, I think it's evident. I can see that clearly because by the time I click check-out at 7 p.m. on Tapeheadcity.com basket random, when 500 new cassettes are re-released (at 1000 quantity apiece), the 20 or so that I want are already sold out. I log on at 6:55 p.m.

This is a great deep dive into The Zombies' legacy and the intuitive connection between Colin Blunstone and Rod Argent. The focus on their harmonies, influence from slither io The Beach Boys, and the impact of keyboards over guitars in their music makes it a compelling read.