No California dates on the 2024 tour? You're killing me...

Mettler: got any pull on this?

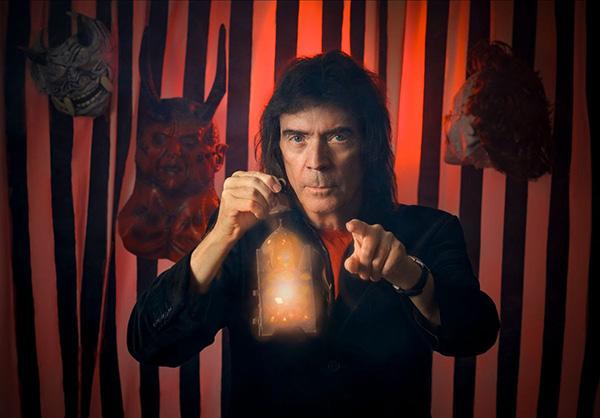

When we last left off with Steve Hackett, he was celebrating the multidisc majesty of his 180g 4LP collection Genesis Revisited Live: Seconds Out & More (and you can read all about it either anew or as a refresher right here). But whenever the calendar turns, almost inevitably, new Hackett music is on the horizon — and thus we have before us the British guitar maestro’s 30th solo album, The Circus and the Nightwhale, which is being released tomorrow, February 16, 2024, as a 180g 1LP set via InsideOut Music.

We’ll get to the vital LP stats in just a moment, but first I asked Hackett to explain what makes Nightwhale different from some of his other current studio LPs. “I think it’s possibly more of a mainstream album than some of the other ones I’ve done in recent years where I’ve used stuff from so many countries,” he admits, “whether it’s been Vietnamese instruments, a charango from Peru, or a sitar from India. All those things have their place.”

That said, Hackett still challenges the ear with aplomb and genre shifts galore from album side to album side on Nightwhale — see the jazz overtones of “Found and Lost,” the whirling dervish that is “Circo Inferno,” and the fully acoustic “White Dove,” for starters. “This is a shorter album — it’s about 45 minutes — and I wanted to employ brevity in terms of solos that didn’t outstay their welcome, and changes that kept. . . (slight dramatic pause) on. . . (slight dramatic pause) coming,” he concludes with a smile.

The LP stats are these. The Circus and the Nightwhale is a 180g 1LP set cut from the 24-bit/48kHz master digital files. The lacquers were cut in-house at Optimal in Germany, and the vinyl itself was pressed at Optimal. Either or both the blue-spatter vinyl (£29.99) or black vinyl (£24.99), each of which are personally signed by Hackett, can be ordered directly from his official HackettSongs site right here (along with the signed £19.99 1CD/1BD mediabook edition, if you so choose).

In a recent Zoom interview across the Pond, Hackett, 74, and I discussed the genesis (pun intended) of Nightwhale music, the importance of deploying volume dynamics whenever possible, and why Genesis was in no way going to compromise the depth and the integrity of the song arrangements they came up with for the initial vinyl release of their groundbreaking September 1972 LP, Foxtrot. He’s a supersonic scientist / He’s a guaranteed eternal sanctuary man. . .

Mike Mettler: Tell me about the “film for the ear” concept you deployed for how you approached making The Circus and The Nightwhale. Where did that idea originate?

Steve Hackett: Well, I think that music, and how it worked with me as a kid, always created pictures. Right from the early days, the things that stood out and were my favorite tracks when I was a child would be “The Runaway Train” [by Vernon Dalhart, a post-WWII favorite in Britain]. My dad used to buy me country records. He was a very sweet man. He played a lot of instruments himself, my father did — just for fun. And he’d buy me Roy Rogers, “A Four Legged Friend” [the B-side to Rogers’ 1952 10in shellac 78rpm single, on His Master’s Voice, “There’s a Cloud in My Valley of Sunshine”], “[The Ballad of] Davy Crockett” [likely the 1956 Tennessee Ernie Ford version on 10in shellac 78rpm single, on Capitol] — all these early, early things. And then he’d play lots of Americana here, you see. He’d be able to play “Oh! Susanna” [a longtime Western standard composed by Stephen Foster in 1848].

Mettler: Did experiencing that world by listening to American artists feel like fantasy fulfillment to you, in a way? You didn’t really have a personal connection to that subject matter and didn’t get to see those kinds of things in your own land — you had to come across the Pond to see it all in person.

Hackett: Yes! Yes, that’s right — but it conjured a picture, and I cottoned on straightaway that maybe country songs were cowboy songs, and we didn’t have any of that here. We didn’t have horses nearby — we had concrete! (MM laughs) We had pollution. We had all sorts of things. I think many of the songs that spoke to me were designed for children to hear. It may well be they came from films — but as far as I was concerned, when I was hearing something like Uncle Mac’s Children’s Favourites on British radio, whether it was “The Ugly Duckling,” or “Three Little Pigs,” “The Big Bad Wolf” — straightaway, your mind is forming pictures. [Uncle Mac (Derek McCulloch) hosted shows like Children’s Hour and Children’s Favourites on BBC Radio during the era Hackett is referring to here.]

All that sort of thing went on through my travels of listening to classical music, where it would give you the sense of flying, or the sense of displaced people.

Mettler: Right, and titles like Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries” automatically gave you a visual cue to lend an image to go with what you were hearing.

Hackett: That’s also part of it, yes. I mean, sometimes an instrumental piece will only have one lyric, and it’s the title of the tune. Or something like [Edvard Grieg’s] “In the Hall of the Mountain King” can lead to [King Crimson’s] “In the Court of the Crimson King” — it’s the progenitors, and it’s the descendants, this whole thing.

So progressive music, in a way, seems to be the sum of program music and classical music. Program music is music that tells a story, and progressive music seems to do that. I mean, I prefer the term inclusive music, so that everything is welcome in it.

Mettler; Oh, copyright that phrase right away. Inclusive music, I’m writing that down. I love that. That’s going right into the title of this story.

Hackett: I don’t think it’s ever going to supplant prog, the four-letter word. But I think inclusive music, and also the description of pan-genre music — is, “all styles welcome.” Nothing off-limits, like in wrestling — no holds barred! (both chuckle) That’s the idea. There are no limits.

Mettler: Getting back to Nightwhale, the first phrase sung on the album is “falling down stairs,” right? That’s the first thing you mention in “People of the Smoke” (Side 1, Track 1). Is that a specific incident that happened to you personally?

Hackett: Yes, yes. It was. It was something in my life. I remember when I was a child, I was climbing up the stairs of the first home I was in up to the age of three. Somebody knocked at the door and I lost my balance, and I tumbled to the bottom of the stairs, probably wailing at the top of my lungs.

So, “falling down stairs / in the hall” and then “fog in the alley” are all from my youth. I remember lots of fog. Not just when I was young, but also when I was in my teens. Sometimes the fog would get so bad they would send you home from school. I remember this happening in the 1960s, and I believe the Battersea Power Station — the one you see on that Pink Floyd album cover [January 1977’s Animals] — wasn’t decommissioned until the 1970s. It was still belching fumes, which became clouds. It’s why I described it as a “cloud factory.” The clouds went right into the stratosphere, and it colored the very sky that you saw! I thought, “Oh, maybe this is where the clouds come from.” (chuckles)

Mettler: “Cloud factory” could also describe the scope of what we’re hearing on the new album. To me, Nightwhale is a microcosm of “here’s what Steve can do,” boiled down to its essence. Especially the solo you take on “People of the Smoke” — that’s an example of you giving us “just a taste,” and it only fits in the context of those couple of bars of that song. That’s how it came across to me because we know you’ve got an arsenal of material where you can stretch it out, but this record has a different purpose. Because you’re also giving us a narrative, it needs to be a little more concise as to how you’re getting us from Point A to Point B.

Hackett: Right. I think you’re absolutely right about the idea of narrative. So, a bit like scenes in that imaginary film, we have to be able to keep the pace up if we’re going to retain interest.

I’m very well aware that, with the kind of music I enjoyed greatly in my earlier years, it would be a case of where you would listen to one track and you’d think, “absolutely marvelous.” And then another track, maybe not so great, would come next, so onward you’d go with it. The idea of “onwards” — you know, forward motion — is not lost on me. The idea of, “Well, if you didn’t like that, maybe there’s this you might enjoy because of an influence of such and such,” or “this might be rockier, therefore, you might like that.” Or “you might enjoy this, because it’s a little more adagio, a little more siesta,” or whatever the description of that music is.

For years, when I was doing nylon[-string] guitar albums, I would think of it as “Music for Siestas.” That was it — the idea of not using the term “relaxation music,” which has another connotation. But the idea of music to literally just drift off to — that’s the beauty of it. There’s no tyranny of volume with acoustic music, and that’s one of my other passions — just the sheer beauty of it.

Mettler: You’re nothing if not a passionate artist, that’s for sure. Now, I’ve also seen in this past year or so you’ve been able to reissue a number of your classic albums from the 1990s and 2000s that have never been on vinyl. How did that all come about?

Hackett: I’ll be absolutely honest. These things were driven by my record company [InsideOut Music]. And, of course, we have a heavy, heavy touring schedule, so what I do is, I take the boxes, I sign as many albums as I can for pre-orders, and sometimes we also bring some of them on the road with us.

But I certainly didn’t remix anything. Things were remastered, and I would check them where possible. I realized that this [the Nightwhale LP] is my 30th studio album, and the record company seems to want to ride this good wave I have and put the catalog back out there. There’s a lot of interest in the stuff from my catalog and, well, who would have thought? But there you go.

Mettler: The beauty of having a deep catalog like yours is people can go back and say, “What’s this Darktown thing all about?” [Darktown was initially released on CD only in May 1999.] And then they find a world they never knew about, because it wasn’t available to them to play on vinyl. I also like that you have color vinyl choices that match the artwork. There’s that transparent light blue option that perfectly complements the To Watch the Storms cover. It just fits. [To Watch the Storms was initially released on CD only in June 2003.]

Hackett: I think giving people choices is the important thing. We’re in a world where people are saying, “Well, download rules.” But actually, I think there’s the converse argument — and I think we’re coming from the other school.

Mettler: Agreed. In regard to those solo releases, is there one track from the canon that you’re most happy about having now gotten onto vinyl, and why?

Hackett: Yeah, okay — it’s a track called “Marijuana Assassin of Youth” [Side 4, Track 1, from To Watch the Storms]. I’m really pleased that it’s on [2LP] vinyl because it was on the special edition when it was CD only. It goes through a lot of changes. It contains Bach, it’s got the Batman theme, it contains “Wipeout,” and “Tequila,” and it goes through all that — and then there’s a sort of George Thorogood thing, and there’s some Jeff Beck influence in there too.

Mettler: Oh yeah, it’s loaded. It’s totally loaded! (laughs)

Hackett: (laughs) Yes, it is! There are a lot of things in there, like “London Bridge Is Falling Down,” all done with the whammy bar — very Jeff Beck. Yes! I think you might like that one. I’ll be interested to hear what you think of how that one sounds on vinyl.

Mettler: Well, I’ve ordered it directly from your site, so you know I’ll be reporting back on that.

Mettler:: But now, I need us to revisit something I promised to get to posting here on Analog Planet the last time we talked [in 2022]. Around that time, I had also talked with Nick Mason of Pink Floyd about the fact that their [October 1971] Meddle LP was pushing the limits of fitting too much information on an album side because both sides of that record ran about 23 minutes apiece, and were dangerously close to having the needle jumping out of the groove. He may have even said they almost had 26 minutes prepared for one of those sides before they had to dial it back.

Hackett: We had the same thing with [September 1972’s] Foxtrot. On Side 2, we had “Horizons,” which is a short hors d’oeuvre before the main course, which is “Supper’s Ready.” Now, “Horizons” is only about 90 seconds long but it’s acoustic, and it doesn’t eat that much groove. Same thing with the beginning of “Supper’s Ready,” where you have three acoustic guitars — all playing simultaneously, and often playing the same part, and that’s also not eating a lot of groove.

So, you’ve got that song, which is 22, 23 minutes long, plus “Horizons” — and, again, it’s pushing it, but Genesis, to a large degree at that time, was hugely influenced by folk music and classical music, so all those things were possible. They were all part of the mix, but it went from a whisper to a roar. That’s part of the appeal, I think — the dynamics that were possible during that pre-MTV era where nobody was producing the perfect length of a single to a record company. You had “Supper’s Ready,” you know? — 23 minutes long, and the perfect length for a single, right? Not.

Mettler: (laughs) A single times five, maybe.

Hackett: Yeah, that’s right. Yeah, well, you want a maxi-single? There it is! (more laughter)

Mettler: The other thing related to what you’re mentioning here is the importance of sequencing. Clearly, in those days, it was super-important — and it’s still important for you now, as a composer. But even then, you were essentially sequencing based on, “Well, if I want to do a 20-minute song, there has to be a lot of acoustic content or we can’t even fit it on here.” Because of that technical limitation, you almost had no choice but to compose it differently. Is that fair to say?

Hackett: Yes, absolutely, at that time — but I think it was quite accidental. Had we not been able to fit that on, then something would’ve had to have been left off the album. But luckily, there are some great tunes on it.

Last time we talked, I’d been revisiting it [Foxtrot] in order to relearn those parts. Now, many of them I was familiar with, but ones I was less familiar with are “Time Table,” for instance [Side A, Track 2], which I think is a beautiful little gem that I think got bypassed. It’s lovely on the remix Nick Davis did in recent years [for the 2007 reissue] where it’s got all the sparkle I remember when I was just rehearsing it with a Les Paul guitar and Tony [Banks, Genesis’ master keyboardist] on an upright piano. And now, you hear that remix and it’s got all the sparkle, and something of a slightly Beatle-ish feel at times, since my guitar work was pure George Harrison at the time. That’s what I was aiming for when I did that, just to give the piano extra sparkle by putting the guitar through two Leslie cabinets — an old Beatle trick. That was quite lovely.

And it’s a very modernist level of playing from the band. Nobody is playing heroically. We’re all accompanying the song to give it its best ensemble feel. That’s not something you get a lot in rock where people are strutting their stuff. That’s the hallmark of modern rock as we know it, but to be restrained and to try and serve the song, I think, is hugely important.

I loved reacquainting myself with that song, and also parts of “Get ’Em Out by Friday” [Side A, Track 3] — very complex, very tricky. And also, “Can-Utility and the Coastliners” [Side A, Track 4]. I basically presented the song and lyrics to everybody, and they said, “Great.” But then you’ve got a band arrangement which follows with refined jams and all that, and then it becomes more complex as it continues.

There are moments which sound like beautiful classical music, but you get thunderous drums and a bass pedal and toning like a bell from a synthesizer that sounds like a storm at sea to me, and I think it’s hugely successful. I love it as a moment of music. I think it’s one of Tony’s best solos on top of a band, with him essentially improvising.

Mettler: You’ve always been great at testing how much dynamic range you can use on any given track and any given side — to be able to take the full spectrum of sound and give us those volume dynamics, or however you wanna quantify that.

Hackett: Yeah. I think that that’s important. The concept of crescendo is important. Oh, there are other things you can take from classical music, but I think that’s a very important one with progressive stuff, so that you’re not thinking in terms of — if it’s loud from the beginning, there’s nowhere to go. You’ve got to break it down.

There are many Genesis tracks — usually the long ones — that start very quietly, and end up being very loud. At some point, it was a trait of the band. It was part of what characterized the band — and people didn’t get it at first. They often wanted to boogie, and to bliss out to that — and Genesis just wasn’t giving them that. But when we had the light show and the stuff became more well-known, the presentation was hugely important — and I still feel the same way.

Mettler: I’m glad you do. Well, let me ask you this quickly so it can be our own version of “Los Endos” (both laugh), since we have to get going. Let’s now project ourselves 50 years into the future, into 2074. Unless science has come up with something magical, probably you or I will not be on the planet then, but if somebody cues up Genesis music or Steve Hackett music in 2074, what do you want them to get out of that experience?

Hackett: Well, my great friend Richie Havens said, famously, after I’d recorded with him [for April 1978’s Please Don’t Touch] — he said to me, “This is the classical music of the future.” Then he said, “I’ve been trying to sound like this for years.” I’d only been on two tracks with him [“How Can I?” and “Icarus Ascending”], and I had hoped to produce a whole album because I knew that some of his stuff — well, you may think of him as a folk performer, but he was an orchestra in spirit. [Sadly, Havens passed away in 2013 at age 72.]

So, what I’m hoping is that Richie’s prediction comes true, and that there is a legacy that’s worth preserving with this music.

STEVE HACKETT

THE CIRCUS AND THE NIGHTWHALE

180g 1LP (InsideOut Music)

Side 1

1. People Of The Smoke

2. These Passing Clouds

3. Taking You Down

4. Found And Lost

5. Under The Ring

6. Get Me Out

Side 2

1. Ghost Moon And Living Love

2. Circo Inferno

3. Breakout

4. All At Sea

5. Into The Nightwhale

6. Wherever You Are

7. White Dove

No California dates on the 2024 tour? You're killing me...

Mettler: got any pull on this?

Mr. Hackett has the rare ability to play pretty without sounding precious - Cf "The Carpet Crawlers". Glad he's still at it.

---

I haven't done my customary thread hijack in a while. Folks said they enjoyed past installments, so here I go again. Any (or all) of these will make you sofa dance. And the sound quality puts all that tinkly-bell breathy audiophile nonsense in the shade.

Joe Tex "I Gotcha" Dial (US) D-1010

The Jam "Going Underground" Polydor (UK) POSP-113

Donovan "Hurdy Gurdy Man" Pye (UK) 7N-117537

They were big sellers in their day so they're plentiful and cheap. Thank me later.

Agreed re: Shuggie Otis. I believe Strawberry Letter 2 is widely hailed as one of mankind's greatest achievements.

With respect to my recommendations, I should add that they are all cut at 45RPM. Because they're singles. I couldn't bear to see folks scouring the LP bins in vain...