Tony Levin on Getting Down to His Signature Low-End Business on Stunning New 2LP Solo Set Bringing It Down to the Bass, Plus Revisiting 1980s King Crimson With the Four-Man BEAT Collective

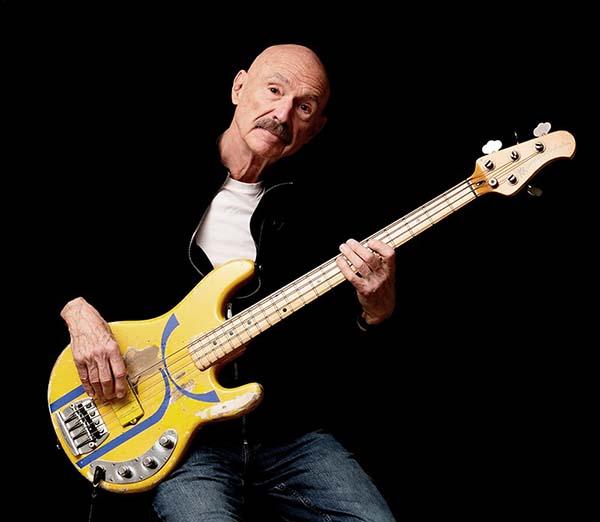

For many of the interesting, innovative, and forward-thinking, progressive-leaning recordings of the past half-century-plus that we live for and love on vinyl, Tony Levin has been both their heartbeat and anchor. Whether it’s with King Crimson, Peter Gabriel, Paula Cole, ABWH, Stick Men, or scores of other artists’ albums that number well into the 500s, Levin’s signature bass tones immediately let you know, “Now, this is going to be a rewarding listening experience.” Or, as Levin himself oh-so-succinctly puts it, “A lot of us share that passion we grew up with for music that takes twists and turns through your life. But if you’re lucky, you get to indulge in that passion throughout your life.”

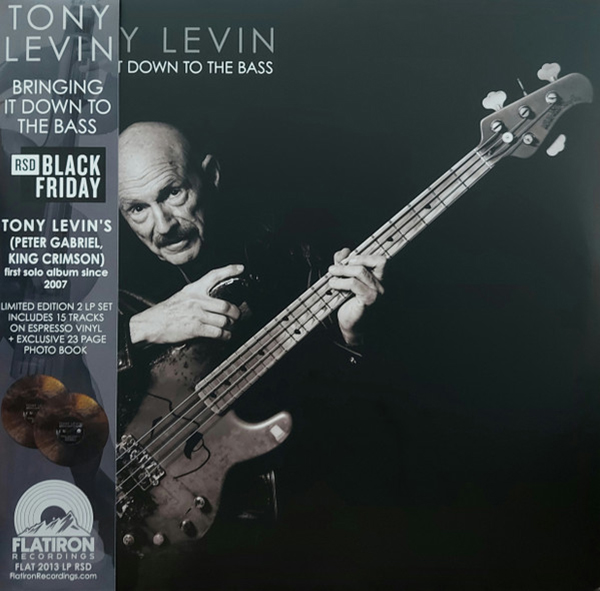

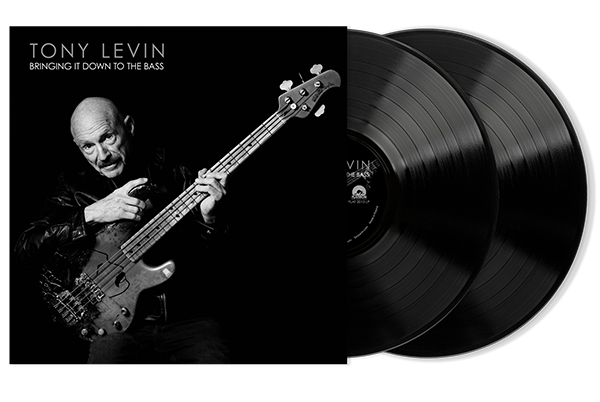

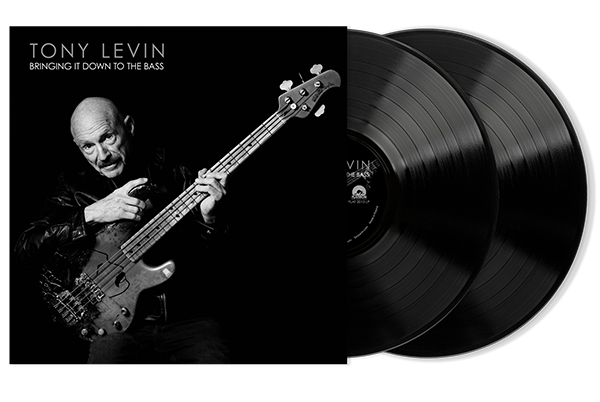

Case in point is the breadth of music to be found on Levin’s new solo album, a mighty 2LP set rightly dubbed Bringing It Down to the Bass (Flatiron Recordings FLAT 2013 LP), a.k.a. BID2TB, which was also one of my Top 5 LPs of 2024.

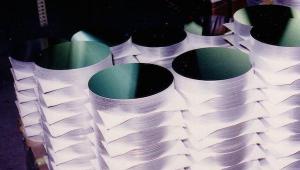

I asked the head of Levin’s label, Flatiron Recordings founder and CEO Bill Hein, to confirm all the important techie stats regarding the BID2TB vinyl, and he happily obliged. The source material used to cut the vinyl came from 24-bit/48kHz WAV files. “Brian Lee and Bob Jackson at Waygate Mastering — the former Bob Ludwig studio in Maine — mastered the album. They did a great job!” Hein told me. “They sent the mastered WAV files to our Pressing Business factory in Boleslaw, Poland — which is under the same ownership as the Flatiron Recordings label — where we cut the lacquers on a Neumann lathe. Waygate created separate masters for vinyl, CD, and hi-res streaming optimizing for each format.”

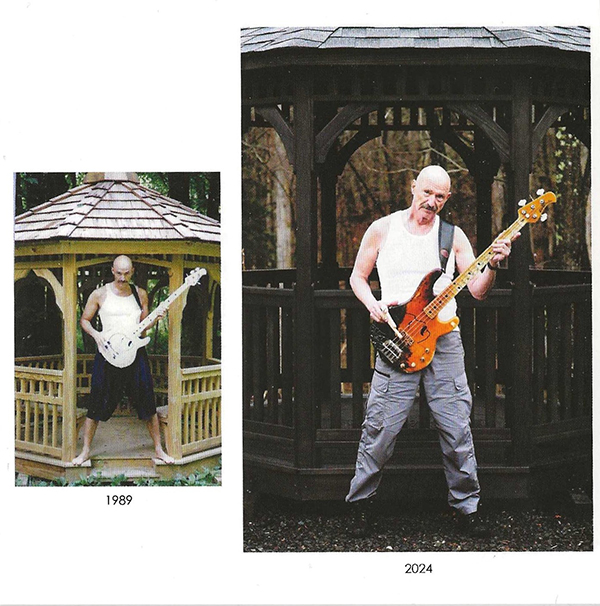

I then asked Hein how easy and/or how hard it was to incorporate the 24-page, bass-laden photobook within the BID2TB 2LP set’s gatefold packaging. (The booklet’s cover image is shown above.) “The photobook was hand-glued to the inside the gatefold. It’s not super-complex, but it requires time and especially attention to detail, which our factory is good at,” he replied. “We do print in-house, which gives us total quality control over the whole printing and pressing process. The album itself serves as sort of a musical biography, and the photos help tell the story.” All the photos are by Levin, a long-accomplished photographer in his own right, as accompanied by his always-informative, diary-like caption narration.

The initial press run for BID2TB was 3,000 copies on espresso vinyl — deep, dark espresso vinyl, I might add — which was specifically earmarked as a Record Store Day/RSD 2024 exclusive on November 29, 2024. Hein confirmed that they have a small quantity of them leftover (“very small!”) that are available at both the official Flatiron store and Bandcamp for a quite reasonable SRP of $39.98. “There will be a black vinyl run sometime in 2025,” Hein adds — but if you want to express your espresso love for BID2TB in the meantime, you can get your own copy while they last, either at Flatiron here, or at Bandcamp here.

I should also take a beat here to mention that Levin spent the balance of the back half of 2024 touring and performing with BEAT, the four-man Robert Fripp-approved collective who play 1980s-era King Crimson with jaw-dropping proficiency and aplomb. I had the opportunity to catch BEAT — comprised of Levin on bass, Stick, and synth, former fellow KC’er Adrian Belew on lead vocals and guitar, Steve Vai on impossible guitar parts (and beyond!), and Danny Carey (of Tool) on drums — at the Center for the Arts at the University of Buffalo up here in Western New York on December 2, 2024, and I’m still recovering from the jaw-droppingness of it all. (The above photo of BEAT in action is by Jon R. Luini.)

“It’s much more exciting to revisit this music in a different way,” Levin observes of the BEAT manifesto. “It’s a valid and exciting musical experience, frankly, to have Steve and Danny add their own interpretations to this music, because just covering it the way it was in the ’80s wouldn’t be as exciting. Mind you, in the ’80s, we changed it quite a bit on the live shows, and you can hear it. To me, the exciting part now was in letting the music grow and be vibrant and different each night — and there’s room, and there’s latitude, in these pieces to do that.” More live BEAT dates may soon appear here in 2025, all respective schedules willing — and hopefully, an official live, multi-LP recording with be forthcoming at some point as well.

As for the creative juices flowing all across BID2TB, Levin is very much in the groove, quite literally. “I already have enough material for the next album,” he confirms, “but, knowing me, when I get home between tours, I will write more material and see where that takes me — and I will. Hopefully, ideally — and I’m laughing as I say that — I will follow where the music takes me. I think it would behoove me to put out another record within a year, or a year and a half — but whether I’ll be able to do that depends on Peter Gabriel, King Crimson, and BEAT.” Given how good BID2TB is, let’s hope Father Time is on our side — or sides, in this case.

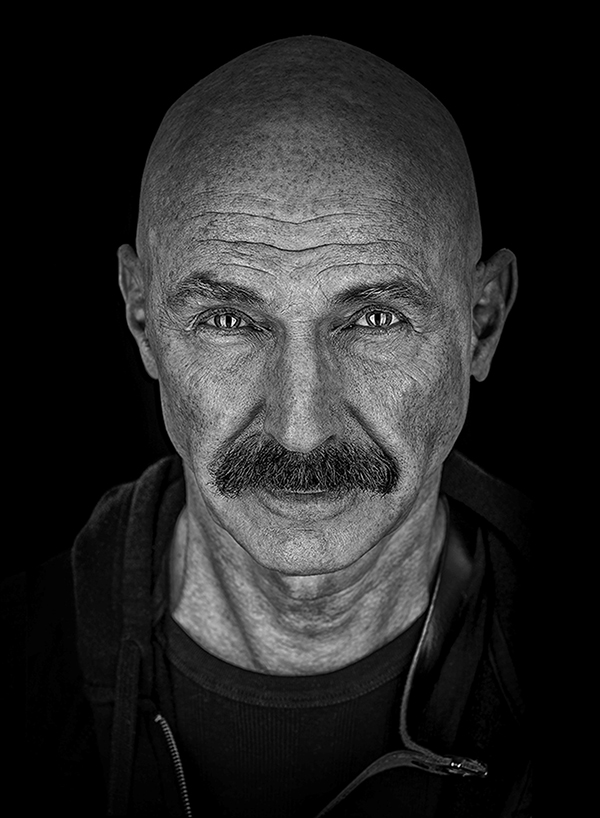

On a recent Zoom call to his hotel room during one of BEAT’s final tour stops, Levin, 78, and I discussed the ongoing wonderment that comes with flipping over LP sides, what his first vinyl recording session was in the 1950s, and the “complicated” decision behind when to sing, or when not to sing. Your spirit flies up in the air / To turn it over, stop the spin / Turn it over, new begin. . .

Mike Mettler: Let’s start with the fact that you doubled things up and decided to give us four sides of Bringing It Down to the Bass. Was that your plan from the beginning — like, “Okay, I know I’ve got to do vinyl here, but how do I do it the right way”?

Tony Levin: Yeah, we always want vinyl. And, in this case, it’d have to be double vinyl because I had a lot of material on the album. You want it, but usually you can’t afford to put the money upfront to have it made, and you wonder what’s it gonna sell. But the record company, Flatiron Recordings, has been very good about accommodating whatever I wanted.

An even bigger request of mine was that I had all these photographs, the portraits I took of all the basses I’d used — more than a few! — and I had stories about them, and I wanted a 16-page booklet. [MM notes: He actually got a full 24 pages out of the deal!] That’s a lot to ask a label involved in the expenses of making the CD, and then the vinyl. And, of course, if you’re a graphic artist, what you aim at — what you dream of — is that 12-inch representation of your work. It’s a dream to be able to create great album artwork — so, yeah, I’m very lucky they allowed me to have that. I got the big booklet, and I got the double vinyl. And, for the special edition for Record Store Day only [on November 29, 2024], they allowed me to have the platters — the vinyl discs — to be espresso-colored. (chuckles)

Mettler: Luckily, I was able to procure my copy of the espresso vinyl locally, right after getting back home from traveling that weekend! Obviously, the sequencing on the CD is different than what’s on the vinyl, so I’m sure you had to make specific side choices. Especially since you’re a low-end progenitor (Levin laughs), you had to be super-careful about where certain bass elements go on any given side. Tell me about the decision process, and how you had to make some serious calls on where to place certain tracks.

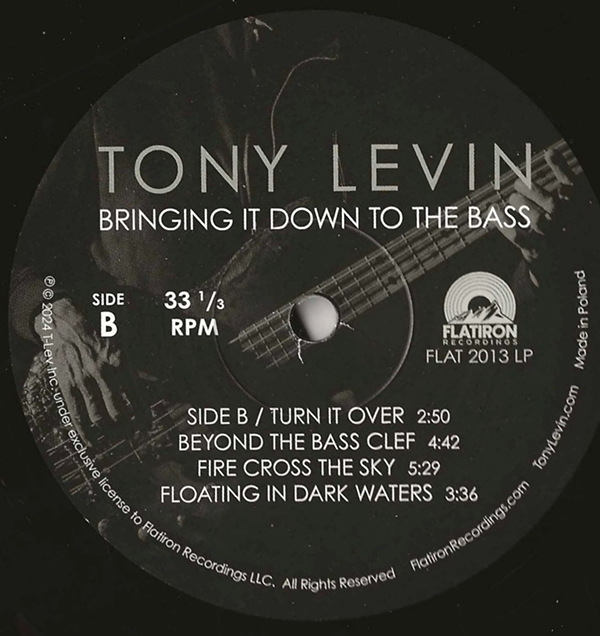

Levin: Yeah. Well, you make it sound like it’s difficult. But when you’re producing your own record, you make those decisions about everything — about the CD, about the Blu-ray and the use of the Atmos mixes, and, oh, do we do double vinyl? “Yeah, fine!” And I have to smile as I think of the one piece I wrote called “Side B / Turn It Over,” which is very vinyl-specific.

Mettler: I was just going to say that “Side B / Turn It Over” is one of my favorite tracks ever, frankly. (laughs)

Levin: (smiles) I wrote the lyrics quite a while ago about — well, I’ll explain from the beginning. I know you’ve done this too. The experience some of us remember about turning your record over — when you think about it, it’s quite an experience. You literally get up from your chair, and everything’s changed. You don’t know what to expect on Side B. It can be blah, or it can be just as good. It can be better, or your favorite thing can be on Side B. So, I wanted to write a piece about that — and, of course, where would I want to put it? At the beginning of Side B! I finally got to do that with the vinyl.

Originally, I planned that this song should be on the vinyl only, and not have it exist on the CD so no one would hear it if they only bought the CD. I like the piece the way it came out so much that I “lent” it, and put it on the on the CD also [as Track 8, if you’re keeping a digital score]. But where it belongs is at the beginning of Side B.

Levin: And, by the way, as it portends, the nature of the music changes a bit with the pieces the come after that song, in a subtle way. That’s all to do with the sequencing one does when one produces an album. I had a lot of choices with double vinyl. There was a lot of room, so I didn’t have to squeeze too much into one side of one platter — which, as you mentioned, can affect the low end that can be on it in the mastering.

Mettler: So true. Now, I’m guessing that you got to hear some test pressings before you went to the final pressing stage. Tell me about that process. Did you have any notes about what you heard on it?

Levin: Sure. Always, notes. Yes, very kindly, they sent me tests of the masters of everything — the mixes, the CD, and the Atmos, and that was a trip because I really hadn’t heard my music in that sense at all before. In all those cases, I had some suggestions — not big ones, because we’ve got very good people to do those things, people who know what they’re doing — but I had some.

And, specifically — uh, geez, I’m trying to think of which ones. It’s a long process, really, and a wonderful process. There was one piece I heard a problem on late in the day, and we had to go all the way back and fix the whole mix, and go back to the beginning. (chuckles) But we did it, because it’s very important.

Being a bass player, I remember that, near the end of a side, you can’t have a lot of low frequencies, or the needle will jump out of the groove, or something like that, because it’s actually going at a different speed. It can be complicated!

Let me digress, and tell you a story you might be interested in. I was recording at a very young age, to put it mildly. My dad was a radio engineer, and every year before my mother’s birthday, dad would bring my older brother Pete, who is three years older, and me into the radio studio, and we would record a little classical piece. Pete played French horn, and I played piano. And we would say, “to muth-uh, on her birthday” — I had a Boston accent way back then! (both laugh), and I have that vinyl now — [sic] nine-inch vinyl, breakable, and recorded on one side. It’s really old stuff, from the early ’50s.

I asked dad, “How did you do that?” because I don’t remember. He said, “Well, I got a phone line to Springfield, Mass., where the cutting plant was.” Dad was in the control room, and he would go like this — he would give a “hands down” to me and Pete, and we would start the one take that we would do. We played the piece, and that was the end of it.

So, I was recording direct to disc — to vinyl — at the age of about eight or nine years old. (smiles) It’s ironic that I ended up, for years, becoming a studio player — and, as you can imagine, I wasn’t intimidated by being in a studio, because I grew up in it! (both chuckle)

Mettler: Wow, that’s such a great story. I wonder how much that 1950s recording of The Levin Brothers would go for on Discogs (more laughter) — but anyway! Keeping you in the past for a moment, was there one record when you were growing up that was, as I call it, “The Talisman Record” — the one that, as a kid, you just loved to play over and over?

Levin: My older brother could afford records before me — I’m not the only one with this story — so I was listening to his records first. Mostly, I was immersed in classical. I was a fan of it, and I also listened obsessively to classical music on the radio.

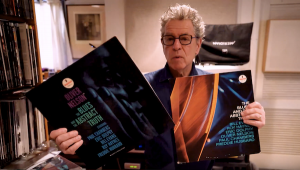

Let me also say that Pete’s records were jazz records because he loved jazz, and he loved the jazz French horn playing of Julius Watkins, so the ones I listened to most had Julius Watkins, and Oscar Pettiford on bass. I didn’t say to myself, “This is the greatest bass player!” — I was a kid — but I grew up with that music, and later came to realize how superb his playing was. And even though I didn’t end up playing jazz much, or that style of jazz especially, I do believe that his musicality on bass influenced me a great deal.

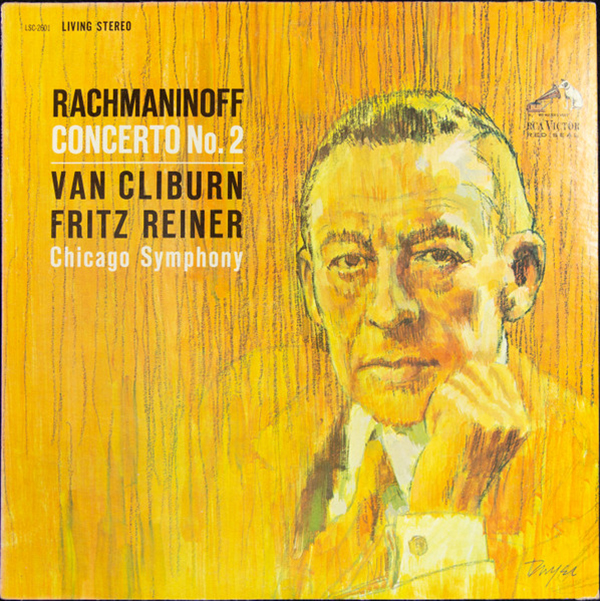

Levin: When it was my turn to buy albums, the one I wore out — and slowed down in pitch (chuckles) — was probably Rachmaninoff’s second piano concerto, Van Cliburn. I haven’t heard that in a long time, so I’ll have to go revisit it. And, like I said, I was a classical geek. When my parents would yell at me to turn off the radio at night and go to bed, I’d be under the covers, playing classical music. (both laugh)

[MM notes: Most likely, given the timeframe being referred to here, Levin had some version of the Concerto No. 2 in C Minor LP by Van Cliburn, Fritz Reiner, and the Chicago Symphony, which was initially released on the RCA Victor Red Seal label in 1962, one example of which is shown above.]

Mettler: Well, we all did some form of “under the covers” listening growing up, that’s for sure. Do you still have any of those records you had as a kid? Were you able to keep any of them?

Levin: I have them, and I don’t listen to them as much as I ought to. On that subject, it’s not because of them and it’s not because they’re old, it’s because I don’t really get much time to revisit music that I like — my own music, or classical music — for a very lucky reason. I’m almost always really involved in the music I’m doing, and that takes some concentration. When I have time to raise my head up from that, I’m involved in the music I’m next doing, whether I’m finishing up a tour or whatever, or if I have some tracks to record at home of other people — and then I’m studying that. This is a good problem to have. (smiles) When I have the time to settle back, I do have a very good hi-fi system and a good turntable at home.

Mettler: What type of turntable do you have?

Levin: I had friends who are audiophiles and much more expert than me, and they told me what to get, so I got it. I have your email, so I’ll send you some photos of my system when I get back from the tour.

Mettler: Great, and I’m happy to show them in the story too. Now, I’m going to go out on a limb and will semi-educatedly guess that you probably have a Technics turntable, probably an SL series model.

Levin: That sounds about right. [As seen above, Levin has a Technics SL-1500 table. His listening system also includes an Outlaw RR2160 stereo receiver (seen below) and a pair of Linn AV 5140 floorstanding loudspeakers.]

Mettler: Thanks in advance for sharing your system! Back to the new album. If you don’t mind me saying so, if somebody doesn’t license “Espressoville” (LP2, Side C, Track 1) as a movie theme, then I don’t know where people’s heads are at (Levin laughs), but that one needs to be like — maybe not for James Bond, but it should be for some type of spy thriller because that’s where it would fit, to my ear.

Levin: Right? (continues chuckling)

Mettler: And then, when we get to hearing some of your vocal stuff on Sides B and D, I feel like you’re almost doing something like what Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top did with vocal manipulation on some of their more experimental tracks in the late-’70s and early-’80s on songs like “Manic Mechanic” [on November 1979’s Deguello, on Warner Bros.] and “Heaven, Hell or Houston” [on July 1981’s El Loco, also on Warner Bros.]. You could still tell the character of his voice, but he played with it a little bit — and it seems like you’ve had some fun here doing that too with your voice.

Levin: Well, let me tell you about two things. My putting vocals on an album of mine is either an afterthought or, sometimes, I have something I wanna say that’s vocal, and I am pretty scrupulous about putting it on. Usually, I start out by not wanting to put it on because I’m a bass player and I do that unquestionably well, or unquestionably better than I sing. (chuckles) But sometimes, you have something to say. Anyway, on this album, as opposed to my past albums, I decided to let myself do what the music seemed to dictate, and not double-question myself.

So, I made a number of decisions, including putting in vocals that have no bass and just no instruments — just the vocal alone. And a very good example of it is the piece called “Road Dogs” (LP2, Side D, Track 1). It’s an instrumental, and I aimed it as having a good groove with the funk fingers — this technical way that I play the bass. Then the melody, it’s kind of heavy. I would describe it as a little bit heavy rock, and then the bridge goes a little bit progressive because it’s in 7/4. Then it breaks down into a shuffle and the melody comes back, played with a guitar kind of sound.

Levin: I’m spending weeks doing the rough of it in my home studio, and I had the thought of doing something I always wanted to do, which was to put the fretless bass through a vocoder. For those who don’t know about the vocoder, you can combine your voice with it so it sounds like an instrument, but it’s saying words. I thought, “Oh, that’s going to be great. I’ve always wanted to do that — and this is the time to do it.” But I didn’t have the pedals or the effects to do that yet, so I put a note in my mind that I’m gonna record this with a vocal, just to remind myself because it could be months from now when I get the pedal, you know what I’m saying? And I sang these words (growls a bit, and extends the vowels): “Road dogs, road dogs / We’re nothin’ but road dogs.” I did it with that kind of voice, trying to simulate what a fretless bass might sound like through a vocoder.

Fast forward, and I got a few kinds of vocoders. I tried ’em, and it just sounded terrible. It just was a worthless idea. I kept going back to, “Well, this scratch vocal I did — even though it wasn’t a vocal piece, if I did a few more words later in the piece, it could be a vocal piece.” It’s a very unusual kind of thing and normally, on my other records, I would have said, “Well, okay — good idea, but this is an instrumental. I won’t use that.” But for this one I had to say to myself, “That’s where the song took me, and I’m just going to leave it.” It’s unusual, four minutes into a piece, to have a little vocal come in that’s the main theme of it. And now we have a very cool video for it too. [MM notes: The clip for “Road Dogs” premiered on Tony’s official YouTube channel on January 10, 2025, and we’ve duly embedded it a few grafs earlier for your enjoyment.]

Mettler: It’s a very clever song — and so is “On the Drums” (LP2, Side D, Track 2), where you namecheck all the great drummers you’ve worked with over the years. One other, shall I say, complicated vocal moment I have to mention is something you did on “Three of a Perfect Pair” [the title track to King Crimson’s March 1984 album on E.G./Warner Bros.], which you played during the BEAT show I saw back in December [2024]. You sing one word, “complicated,” but you don’t do it every single time on the chorus; you do it selectively. I’m just curious — is that a conscious decision, like, “I’m doing it on these two choruses and then I’m skipping this next one, and then I’m doing it again on the one after that,” or. . .?

Levin: It’s an answer. Adrian [Belew] has the main theme, and I answer him — or not. It depends on a whole lot of things. (chuckles) Yeah, nobody’s going to miss it if I don’t do it every time. Sometimes, unlike Adrian’s, my voice gets tired. I’m a normal human being, unlike Adrian. (more laughter) Sometimes I’m resting my voice, or sometimes it musically doesn’t feel like it calls for it that night.

Mettler: Well, maybe I’m the only one who does miss it, “complicated” decision-making involved or no. I never get tired of hearing that song live, or on record. (chuckles) But anyway, I know you have to get going, so I wanna close this down by throwing us 50 years into the future. So, it’s now gonna be 2075, and as I like to say, unless there’s some weird science going on, you and I are probably not physically on the planet then. However people listen to music at that time, and they type in “Tony Levin,” “King Crimson,” “Stick Men,” “Peter Gabriel,” “BEAT,” or whatever else you’ve played on into their listening device, what type of listening experience do you want that future listener to get from the music you’ve made?

Levin: I would say, in my opinion, that’s not a different situation than someone who listens to it tomorrow. You put your music out, and you hope that it connects with someone. You hope that it moves them in some way. And if they’re a musician, you hope that maybe it will inspire them in some way to — not to improve their own music, but it will be one of the thousand things that bounces off them and moves them to do things differently than they would have before.

That’s what you hope when you release your music, and you let it fly out into the world. You don’t really know if that’s going to happen. It could reach 1,000 people, or 10 people, or one person. Some young kid in the Philippines listens to it, and he gets an idea to create something differently. The music you put out has a life of its own and, once you let it go, it becomes separate of you, and you just hope for the best. You put it out there, and it connects with someone or it doesn’t, on its own merit.

TONY LEVIN

BRINGING IT DOWN TO THE BASS

2LP (Flatiron Recordings)

LP1, Side A

1. Bringing It Down To The Bass

2. Me And My Axe

3. Boston Rocks

4. Uncle Funkster

LP1, Side B

1. Side B / Turn It Over

2. Beyond The Bass Clef

3. Fire Cross The Sky

4. Floating In Dark Waters

LP2, Side C

1. Espressoville

2. Bungie Bass

3. Give The Cello Some

4. The Bass

LP2, Side D

1. Road Dogs

2. On The Drums

3. Coda