there is a god.

Exclusive: Producer Giles Martin Talks About the Mixing and De-Mixing of The Beatles’ Revolver for Vinyl

Last week, I told you about strawberry fields, where — sorry, wrong Beatles reference. One, two, three, four (cough) — last week, I told you how it will be on October 28, when Apple Corps Ltd./Capitol/UMe will be releasing The Beatles seminal August 1966 album Revolver in a 180g 4LP/1EP Special Edition Super Deluxe box set. (You can go here to read all the details regarding what comprises that release.)

As noted in that story, AnalogPlanet was granted an exclusive interview with Revolver box set producer Giles Martin, and he was more than happy to speak with me back on Tuesday to address our questions about the vinyl mixing and de-mixing processes, among other pressing analog-related Beatles subjects.

To that end, following a pair of Revolver playback sessions the man conducted at Republic Studios NYC on September 13, Martin, 52, and I got onto Zoom together to discuss mixing and de-mixing Revolver, the “analog vs. digital” question, what Paul McCartney told him when they both listened to the new and original Revolver mixes together, and who ultimately makes the final calls on anything he mixes for The Beatles. Nobody can deny that there’s something there. . .

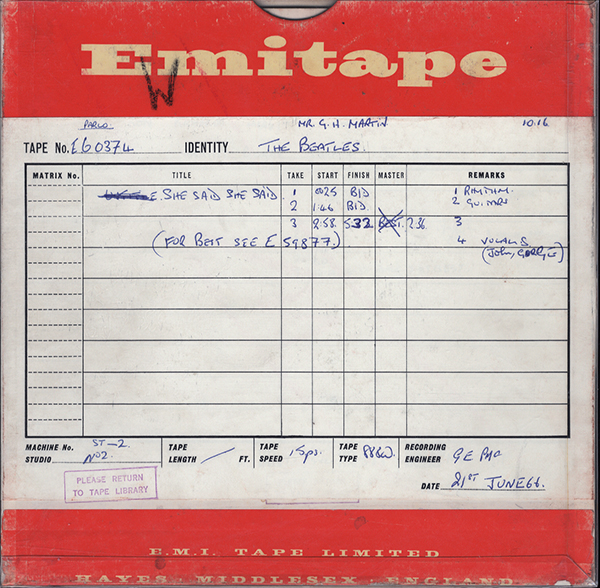

Mike Mettler: To wind things back to the beginning, so to speak, could you give us the literal chain of custody for the original Revolver tapes? Qualify for me exactly what masters were used for both the mono and stereo vinyl.

Giles Martin: The mono is a straight, pure transfer of the mono master. The stereo is a stereo mix that has been remixed, and the other one [the mono] hasn’t. There’s no point in me doing a new mono mix. Someone asked me about it today — like, “Why don’t you?” There isn’t any point, really.

The stereo is the original four-track tape, transferred digitally. I’d been working with the Peter Jackson [de-mixing] team in New Zealand about seeing whether we could take elements off that tape so we could create a new stereo mix, which we were doing. It’s a huge, laborious process, but incredibly effective — incredibly effective. It’s like, I can take the “Taxman” drums, bass, and guitar, and the drums sound like drums, the bass sounds like bass, and the guitar sounds like guitar — and they completely phase-cancel. If I put them back together again and play them against the original and switch to phase, there’s no transients, no noise — nothing. So, I know that I’m not taking or adding anything to that, and it just gives you a bit more impact on the mix. I can now de-mix the drums, and have the kick drum and the snare drum separately as well.

Mettler: Now tell me, from your point of view, what the de-mixing process is, and how that helped “unlock” things for you. I know it was also used for the Get Back project. [Get Back is the 8-hour Beatles documentary directed by Peter Jackson that initially streamed on Disney+ over three consecutive nights in November 2021, and is now also available on Blu-ray and DVD, albeit sans any extras.]

Martin: I think the simplest thing for people to understand it, and the best way to explain it is, imagine having a cake and saying, “Okay, I want to make a different cake, but I haven’t got the ingredients. What I have to do is, I want the butter. I want the flour. I want the milk. I want the sugar. I want the eggs — and I want them all separated so I can make a different cake with them.” That is the technology. It’s like taking something that’s already been baked, and then cutting out the original ingredients.

And it’s incredibly complicated! I don’t really know how it works is the answer, but I know that it works. I know the AI is extraordinary, and it takes huge computer power to do it. I know Peter Jackson’s audio team in New Zealand have a unique talent, and they can do more with it than anyone else can, really. Imagine talking in a crowded room and me putting your voice into a computer, and then hearing your voice isolated and clean. Essentially, it’s AI.

Mettler: Is there one best “cake moment” for Revolver where you were like, “This is what de-mixing was meant to help me do”?

Martin: No — it happens all over the stereo, actually. But certain cases are interesting enough where I could separate the acoustic guitar and the drums on the other side of the brain completely — but it doesn’t sound right if I do so. The acoustic guitar sounds like it needs the drums near it, you know. There are certain things where you feel like you’ve lost your keys — like something has gone missing.

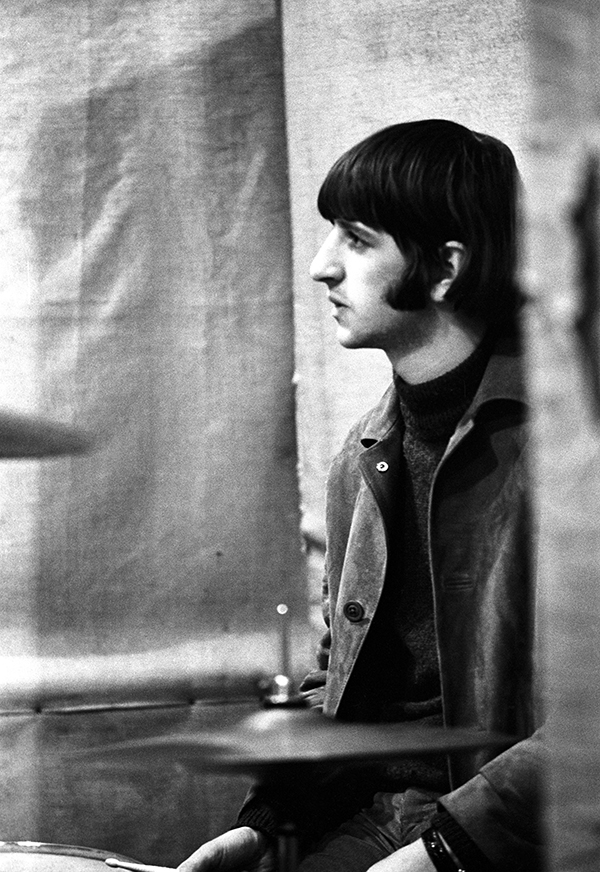

One of the best examples where people can hear it where the lyrics are sparse is “Taxman,” where the drum is in the middle, the guitar is on one side, and the bass on the other. You’ll hear things like, on “And Your Bird Can Sing,” the guitar being away from the drums. “I’m Only Sleeping” — the same thing. You’ll hear the bass being away from the drums, on occasions. I mean, you’ll suddenly hear drums, like the kick drum in “Here, There and Everywhere” and “For No One,” which means the drums have been taken off that track, which is very compressed, and suddenly you’ve got Ringo [Starr] on his own. Therefore, I don’t have to make him louder — I can just give some more dynamics to it. You’ll hear it throughout. It doesn’t have to be positioned, of course — it can also be done with dynamics as well.

Mettler: Was there any de-mixing involved with “Eleanor Rigby”?

Martin: “Eleanor Rigby” was the only track that had no de-mixing on it. It didn’t need it. “Eleanor Rigby” is the only bounce, with the strings — the octet, which is a double string quartet with two people playing the same instruments and the same part. That was recorded on four tracks. And then, that was bounced to another four-track. It was a stereo “Eleanor Rigby,” and then the vocals [by Paul McCartney] were recorded on top of that. So, I didn’t need to do any de-mixing with “Eleanor Rigby.”

Mettler: For those people who have this little asterisk in their head about “the digital thing” being involved in the Revolver process, what is your response to that line of thinking? What do you say to them?

Martin: Yeah — I just say, we don’t listen to ones and zeros. We listen to soundwaves. So, listen — I love tape, and I work with old gear and compressors. Here’s the interesting thing. I worked on a George Harrison film called Living in the Material World [which was released in October 2011], and I did an album from that [called Early Takes: Volume 1, released in May 2012]. I remember the vinyl cut of that sounded more digital to me than the digital version because of the way it was cut — and I wanted to go change it.

It’s like we have too much bias in life anyway — too many preconceptions. People decide they want to hear something in a different way, then they do hear it a different way. I mean, a) I’m not deleting anything people already have, but b) I couldn’t do what I do if I was working in a purely analog domain. It would be impossible. It’s as simple as that.

Here’s the other thing. Most people who talk about this stuff — they’re not listening to songs. I don’t get touched by that. I like the idea that — I hope that I can do things and work on material that brings people closer to it. You know, I have this incredibly privileged position of being able to walk into Abbey Road [Studios] on any day and listen to a four-track tape where I can hear — and I swear to God — it sounds like the band are in the room with me. That’s what I’m trying to get people to listen to.

And, bizarrely, I’m trying to take away technology. People don’t realize, I’m actually trying to take it away. I had this meeting recently with some people who were talking about compression. “But, see, you do realize that all music is compressed or limited — it has been for years. There’s only a small period of time between like 1972 and 1979 where there wasn’t heavy, heavy limiting.” And I was like, “Well, what were your favorite records?” They were like, “’Sultans of Swing’ by Dire Straits [from 1978], and also toss in some Pink Floyd” — all kinds of stuff from that period of time. It’s amazing how many preconceived rules people have in their head about things.

Mettler: And, really, you actually do have to listen to something before you decide you like it, or don’t like it. If you like the mono, it’s gonna be in the Revolver box set. If you want the stereo only, you can buy it separately. Like you said, you’re not taking anything away from anyone. You’re giving people the option: “Here are X number of versions.”

Martin: And when it comes to the vinyl — I mean, we are in the digital domain cutting the vinyl, but it does mean we can do a half-speed cut, for instance. That means we get a more accurate cut, and a better-sounding vinyl. [Note: All Revolver vinyl is being pressed at GZ, in the Czech Republic.]

Mettler: Was there ever any thought of going with 140-gram vinyl for Revolver, as opposed to 180-gram? Did that ever come up?

Martin: No. We didn’t have that conversation, so no is the answer.

Mettler: Okay. For the additional bonus material — the 31 songs and demos — how did you decide the sequencing for them? Was that just by feel, or did you unfold them chronologically for how you wanted people to hear them?

Martin: I think we did it in order of — yeah, I’m pretty sure we did — we did It in order of when they were recorded, because that’s what makes the most sense. In essence, I like to see the additional material a bit like wandering around a gallery, and looking at pencil scripts and paper.

Mettler: Me, I don’t mind hearing 20 takes of something if they exist. I know you can only give us so many extras, but when you played the “Yellow Submarine” demos during the afternoon session I attended remotely, it was kind of like — as you put it — like the Woody Guthrie, “everybody’s dead in the submarine” doom-folk version, and then it turned into something else. Those demos give us a completely different take on a song that turned into something else more, well, uplifting. [Both “Yellow Submarine” demos are parenthetically subtitled as “Songwriting work tape – Part 1 – mono” and “Songwriting work tape – Part 2 – mono,” and they appear as Tracks 2 and 3 respectively on Side 2 of Revolver LP Three, which is dubbed Sessions Two.]

Martin: Yes. It’s that collaborative nature and balance of the song that happens, which is really cool, to me.

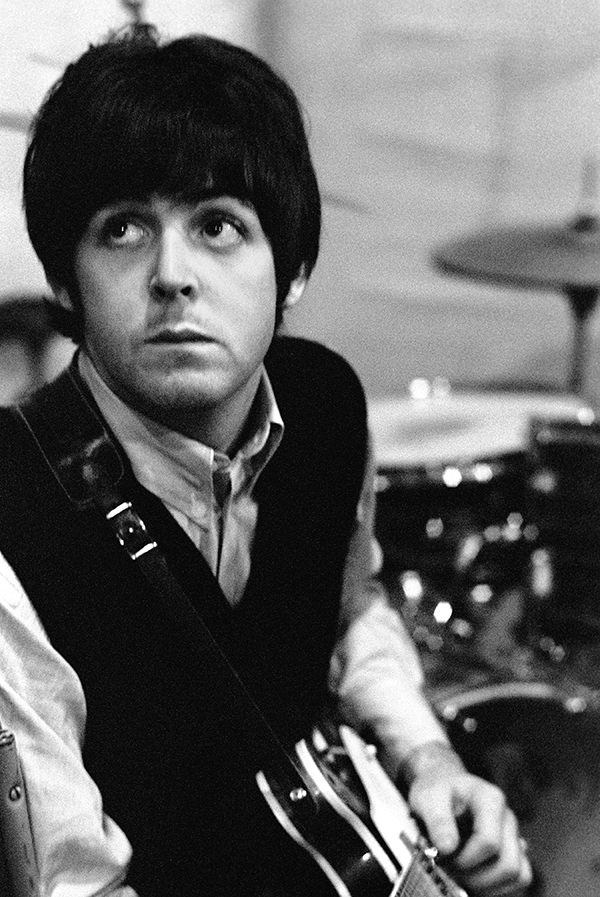

Mettler: Me too. You also got to sit down with Paul McCartney in Los Angeles while you were working on Revolver. Tell me a little bit more about that experience. What did you put on for him to hear, and what was his feedback? Did he give you specific song feedback, or was it just his overall impressions?

Martin: We always do the same thing, me and Paul. We’ll sit together, and — there’s no “sales” with Paul. In fact, it can’t be. He’s too intelligent.

We’ll have a session where I’ll put the stereo mix on that I’ve done, and the stereo mix that he was involved in back in 1966 — and he has a button. He can switch it, and level match, etcetera. With that button, he can switch between the two, and he can tell me what he likes about one, and what he likes about the other. If he doesn’t like what I’m doing, I’ll go and change it. It’s as simple as that.

And he’ll talk about the dynamics. Generally, he’s really happy. When we come across the guitar solo in “Taxman,” which I think I have on the right-hand side, he’ll go, “Let's turn it up in the middle to make it loud,” or say the same with the guitars in “And Your Bird Can Sing.” And then we talk about the song. That’s the way we’ll work through it.

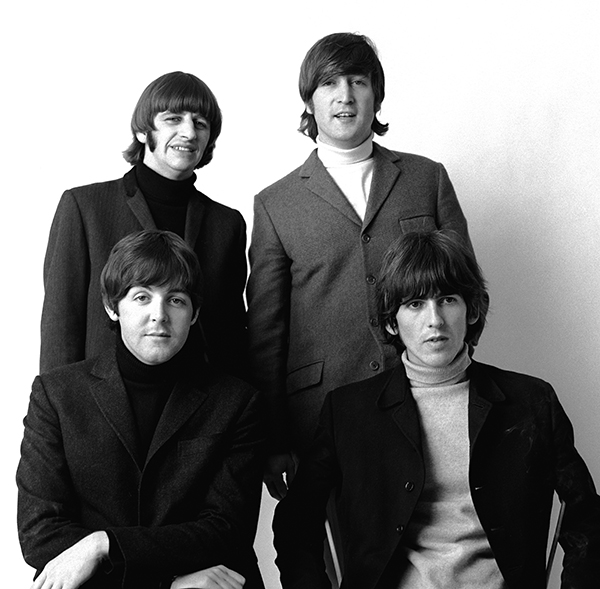

He’s very diligent, you know — I mean, it’s his record. Well, it’s their record, and I’m working for them. There’s a perception, I suppose, that I decide I’ll go off and mix a Beatles album, and then I go mix in isolation. That’s what all these forums say, but they don’t realize The Beatles are quite heavily involved with all this. Of course they are — it’s their record.

Mettler: Right. But all four factions, or whatever phraseology you want to use to quantify it [i.e., Yoko Ono for the John Lennon estate, Olivia Harrison for the George Harrison estate, and Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr for themselves] all have to sign off on whatever’s done, correct?

Martin: Absolutely. And that’s all of it. They’re the only people who have to sign off. That’s it. There’s no record label sign off and there are no A&R teams, or anything like that.

Mettler: Got it. Was there any specific feedback from Ringo, or Olivia [Harrison], or Yoko [Ono] about any of it?

Martin: No. I spent a lot of time tweaking and doing stuff before I get to that stage — before I present it to them — and they were pretty happy, actually. They were pretty happy. But, yeah, Ringo was really happy. I went to play it for him and he was like, “You know, it sounds great.” He goes, “It just sounds great.”

Mettler: Before we go, even though I know you’re not allowed to say what’s coming, just tell me this — how good will [December 1965’s] Rubber Soul sound when you do that album for the next special edition?

Martin: (laughs) Listen — I don’t know. I really haven’t thought about it. I generally have not thought about that yet. I kind of always need a break from The Beatles, so I’m doing no Beatles for the next six months or so, maybe longer. I will be doing some films over that time, and maybe some work for some other people.

Mettler: Understood. Well, is it fair to say that, when it is time to go back to other Beatles releases from 1965 — and even back to 1962, 1963, or 1964 — do you feel comfortable enough to go into all of that early material and do whatever you need to do?

Martin: Not yet, to be honest. We haven’t gotten that far — to look at the [earlier] stereo recordings and do a good job of that. Things get more complicated. Again, you don’t want to do things for the sake of it.

Technology should disappear. It’s like, while you and I are talking to each other, thinking about all the ones that zeros it’s taking for us to talk to each other this way instead of just talking with each other. It's the same with the music. While the technology behind the entire Revolver process is really of great interest and is really quite groundbreaking, I don’t want to “listen” to that. I want to listen to the songs.

- Log in or register to post comments

He mentioned cutting the album in the digital domain. I'm assuming that is what happened with all the LP's.

Thanks for this interview! I thought it was common knowledge that Paul, Ringo, Yoko, and Olivia solely approve everything... so having it on-the-record here should settle that debate. I Giles' statement that the mono is a "pure transfer" to mean it was analog cut; perhaps he's referring to the CD version of this set? Either way, I'm happy with my 2009/2014 CD/vinyl mono editions. Also interesting that he did not need to de-mix "Eleanor Rigby." So if he just remixed it, that's going to sound sumptuous. Finally, I'm glad, MM, that you brought up the earlier albums. The technology probably exists to do "Rubber Soul," and there's not as much de-mixing for AHDN, Help, and Beatles for Sale, so I really think "Magical Mystery Tour" is the next one which needs to be remixed. The fidelity varies greatly from track-to-track, and the 2014 LP is the only decent mono vinyl pressing I know of.

Just an FYI that Magical Mystery Tour has already been remixed, back in 2012 for the Blu-Ray. Lots of Beatles fans swear by those mixes, too ("it's my go-to!"). I recall it sounding pretty good.

Unfortunately you have to rip the audio from the Blu-Ray.

All that said, I'd still like to see it remixed by the current 'administration', as it were, with bonus tracks and such.

What 2012 Blu-ray are you talking about?

Thanks for the great interview. What would be your criteria to say Revolver is the best?

(not ironic question)

Not at all sure it will be done. Have never heard it mentioned as a candidate. The Beatles themselves don't regard it as an "album". There was a UK EP of the TV show songs, and the US "side 2" is just singles that were collected to make it an "album" for US consumption.

Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields were included with the Sgt Pepper remix; All you Need is Love and Baby You're a Rich Man were remixed for the the re-release of the the Yellow Submarine soundtrack.

So what's left? Not exactly the most important songs in the catalog.

I think it is a perfect album and my favorite Beatles record. Not sure why some people give me funny looks when I say Revolver is the Beatle's best album and my favorite. I can't wait to get it.

While I have your attention, I must compliment you on the great postings you have added on AnalogPlanet. I realize this is not a simple exercise and is time-consuming work, but the results speak for themselves. Keep it up.

Well, that's a pretty bold statement. My vote for this would be What's Going On. But, I would not argue that your choice is best in some people's minds. I love The Beatles and their music. I just differ in my take on best of all time.

this would have been a much better album if they had found better songs than George's "I want to tell you" and, especially. "Love You Too". Very weak.

Is the 4 LP box overpriced at $200?

Is that too much to pay for a favorite album with a bunch of seriously desired outtakes?

Well, yeah it kinda is.

Is $140 too much for the deluxe 5 CD version?

In a word, yes.

Like "Pet Sounds", "Kind of Blue" and "The Allman Brothers at Fillmore East" I'll pretty much buy any new version that comes down the pike, so yes, of course I'm getting it.

I don't have to be happy about the price and I'm actually kind of angry about it.

And they wonder why people illegally download this stuff ...

And it sells, anyway.

LP's lets say $30 each

CD's, let's say 15$ each.

In the box set you get the coffee table book, etc. Price for a book like that is $40-50.

Add it up and you get the prices for the sets.

You can always buy just the one disk of the remix and stream the rest, which you probably won't listen to much anyway.

Giles Martin said:

“You know, I have this incredibly privileged position of being able to walk into Abbey Road [Studios] on any day and listen to a four-track tape where I can hear — and I swear to God — it sounds like the band are in the room with me. That’s what I’m trying to get people to listen to.”

What a pity that they are not able to give us (audiophile) consumers that experience. The finished product does not sound like it.

People who heard the Master Tapes always say that they are in fantastic condition and sound fabulous. Neither the 1980s CDs nor the 2009 CDs sound great, although they put a lot of work in it. At least that is what the engineers said at the time.

Why are they not able to transfer that "original" sound into the digital domain or onto LP records (I am not referring to the Mono Box set, although I am missing a Mono Box set in Hi-Resolution and audiophile quality, which means with full dynamics and no added compression and all that nonsense)?

Imagine they would offer the Beatles albums in 24bit 192kHz unfudged. No limiting on peak transients, no Eq. Just edits, fades and fixing bad splices.

You go to the EMI Web site and you order:

EMI PRESENTS FROM THEIR FLAT TRANSFER SERIES – THE BEATLES IN STEREO UNFUDGED AS NATURE HAD INTENDED….

Abbey road playback probably uses the very best speakers and amplification available played back at realistic levels in a large room versus relatively puny domestic hi-fi that most of us use.

It's more than possible that the "flat" transfers sound nothing like the discs. We could do a lot of fudging in mastering.

Gosh, all this fuss and then they press it at GZ, in Czech Republic. A splendid noisy vinyl is guaranteed for all..

The previous 4 Beatles album remixes had Martin going back to the original tapes before mixdowns to a master tape were done to get to more clear recordings of the instruments, and then the remix was built from that. Why wasn't this done for Revolver? Was the new de-mixing AI needed because the supporting tapes don't exist?

I went to work at Columbia in 1971, mastered, mixed, went to WB, went freelance, did more records, mixed TV shows so I'm not inexperienced. The entire concept of mucking around with old records fills me with disgust. Don't you think we knew what we were doing when we made them? I don't care if you're the producer's kid, you weren't there and even if you were you shouldn't be fooling around with these records, or any records. It's not just disrespectful, it's plain wrong for you to impose your judgement in place of the people who made it, who, in case I haven't made myself clear, weren't you and knew what they were doing.