Truly an icon.

In Iceland, my nickname when I was a teenager was "Hönd Flöte."

Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson has been on a deeply entrenched spiritual quest of late. After tackling religious ideology head-on with Jethro Tull’s January 2022 release The Zealot Gene, Anderson felt compelled to go one step further by addressing the tenets of Norse paganism on Tull’s latest and 23rd studio album overall, RökFlöte, which was released via InsideOut Music on April 21, 2023 in multiple formats including a Limited Deluxe Edition consisting of 2LPs, 2CDs, and 1BD, as well as separate 1LP, 1CD, and digital editions.

Incidentally, if you’re wondering how RökFlöte is properly pronounced, Anderson has a few tips for you. “Well, there’s a double umlaut at work there, so it’s Rook, rather than Rock,” he counsels. “Rök is an old Icelandic word meaning destiny, and then there’s Flu-tuh — Flöte, being the German word for the instrument I play [i.e., the flute]. So there you go.” (Got it? Gut.)

To my ears, RökFlöte is a notch or two above The Zealot Gene in terms of its overall intensity and verve on vinyl, as ably demonstrated by hard-driving tracks like “Hammer on Hammer,” “Trickster (and The Mistletoe),” and “The Navigators” (the latter of which you can check out above).

The standard LP edition of RökFlöte comes as 180g 1LP black vinyl, and there are also a host of limited-edition color variants — gold, silver, blue, dark green, dark red, clear, and Coke Bottle clear vinyl. The dark red variant is part of the aforementioned RökFlöte limited edition deluxe box set. In the deluxe edition, LP1 contains Ian Anderson’s original stereo mixes of the album, while LP2 has the “alternative” (their word) stereo mixes by Bruce Soord of Pineapple Thief fame, who also did the alternative stereo, Dolby Atmos, and 5.1 surround sound mixes that are on the box set’s Blu-ray.

The LP pressing stats are these: RökFlöte was mastered at Fluid Mastering in London, the lacquers were cut at Optimal Media GmbH and pressed by Optimal Media GmbH, although two of the limited-edition color variants — the gold (300 copies) and Coke Bottle clear (500 copies) editions — were manufactured by Memphis Record Pressing. The standard 180g 1LP black vinyl for RökFlöte has an SRP of $28.99. Some of the variants run a bit higher than that, and the deluxe box set goes for $99.99.

Anderson wants to make one point abundantly clear about the album’s subject matter. “I am in no way affiliated with paganism of any sort,” he clarifies. “It’s just that I made [The Zealot Gene], an album released in 2022 with, at the root of it, some references to biblical stories and biblical events. And for RökFlöte, I thought I would move on to looking at polytheistic religions.”

Continues Anderson, “I’m not suggesting these are anything other than personal feelings — just examples of the characters and the roles as exemplified in Norse mythology. This, for me, was the amusing way of doing it. It will stand or fail on the basis of the music and the general feel of it, not necessarily a detailed analysis of what it is I’m singing about, or how I’m coming about to sing those particular words.”

Anderson is hardly done following his muse just yet. Not only did he confirm with me that he just approved the mixes Steven Wilson has done for an upcoming expanded edition of September 1978’s 2LP Bursting Out live set (which he sees as the companion piece to the 2009-released Live at Madison Square Garden 1978 collection), but he also notes the delayed updated edition of April 1982’s The Broadsword and the Beast has now been reset for release this July. Plus, he’s already begun working on another new Jethro Tull studio album, tentatively set for release in the fall of 2024. In other words, there’s no rest for this perpetual passion player.

In a recent Zoom interview, Anderson, 75, discusses the inner workings of RökFlöte, when he finally felt like Jethro Tull had gotten the right mix of their music on vinyl, and how the act of breathing is vitally important when it comes to both his singing and his flute playing. I remember yet / The giants of yore / Who gave me bread in the days gone by. . .

Mike Mettler: Was the sequencing for RökFlöte pretty much figured out from the beginning, or did you have to move anything around as you went along in preparing it for vinyl?

Ian Anderson: Well, I had the order set from the beginning — but because of trying to make things a little bit more complementary, and knowing we’d have to split things up in terms of a vinyl product, I did just move a song somewhere else to change the running order for vinyl. But there was only one song, I think, that differed in its position from the original layout.

Mettler:: You did what’s called the “original stereo mix” for RökFlöte yourself, and Bruce Soord did what’s called “the alternative stereo mix.” How did that come about?

Anderson:: Well, Bruce also did a Dolby Atmos mix of the album, and I went to his studio to hear the end results. We didn’t change very much along the way, but I also asked him to do an alternative stereo mix, because it would just have another point of interest.

For the most part, Bruce stuck pretty close — as does Steven Wilson — to my original stereo mixes, but he just changes the emphasis or some sonic qualities, according to his preference and his monitor speakers that he is working to. I did actually ask Bruce to be a bit more radical with a couple of the songs, to make them a bit more adventurous in terms of the mix. But the stereo mix is my original mix as it is mastered. Bruce’s alternative stereo mix is one of the options available in the deluxe package.

Mettler:: Do you prefer just listening to stereo in general? When you were growing up and you were starting to make music, did you appreciate the format, or did you feel that it’s just what you had to work with? What did vinyl mean to you?

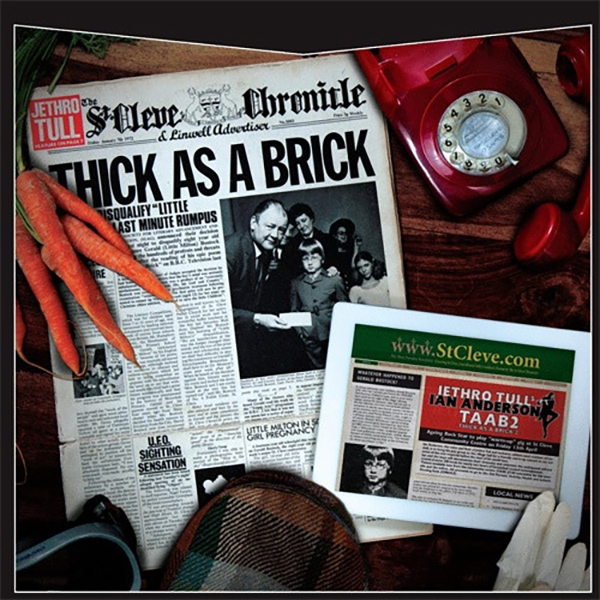

Anderson:: I felt that it’s what I had to work with. I just remember every record I ever made up until about 2012, I think — every record I ever made, when it came to the vinyl result, I only ever felt a degree of disappointment. The first time I’ve had a really, really good vinyl mix was actually with Thick as a Brick 2. And that vinyl was mastered at Abbey Road [by Peter Mew].

[Note: Thick as a Brick 2, which is alternately known by its TAAB2 abbreviation, was credited to Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson, and it was released in November 2012. The 180g 1LP vinyl edition of TAAB2 is only available as part of a limited edition box set that also includes a 2012 remix of Jethro Tull’s original May 1972 Thick as a Brick on 1LP.]

Anderson:: And I have to say, when A/B’ing the vinyl playback compared to the 24-bit digital audio, it was really as perfect as you could get — as long, of course, as you’re playing back something with a pristine, freshly cut lacquer with an absolutely fresh, beautiful stylus. To the average person with average equipment, it’s probably not gonna be anywhere near as good as the experience of listening either on good speakers or good headphones from a download or other digital format you can access, whether it’s high-quality streaming, or whatever.

I’m skeptical about the value of vinyl, but it means a lot to a lot of people who like a retro thing — even if, in some ways, it can border on being a little impractical. But I do understand the retro experience, and I can understand why people like vinyl.

Mettler:: I’m glad you do. Now, if I remember this correctly, when you were growing up, wasn’t it your brother who got you a Bill Haley single? Was that the first actual record you had?

Anderson:: Well, I listened to some of my father’s 78rpm, big-band jazz things from the wartime era when I was a child — you know, seven, eight years old. When I was nine, my brother, who had emigrated to Canada, sent me back a vinyl record, Bill Haley and His Comets — disappointing, because when I asked for a rock & roll album, I don’t what I was thinking of, but I expected something a little bit more gutsy, a bit more defiant. And Bill Haley was just like somebody’s dad or uncle. He had no real credibility as a revolutionary in the world of music. It was cheerful, singalong hillbilly rock, I suppose.

But Elvis [Presley], in the early days, had a bit of something a little meaner — a bit more controversial, that, in a sense, appealed. Certainly, after his first three or four singles, he started getting into movies and was being really cheesy. I was never really an Elvis fan, but it kickstarted something.

The greater impact on me was listening to Black American folk music that you call the blues. The world of Chicago blues and country blues appealed to me as a teenager — and that was what got me actively engaged in trying to make music, because it was much easier to see some kind of emotional and tortured and defiant credibility in Black American blues than it was in the pop music of the day, or the endless Elvis imitators we had in various countries in Europe.

Mettler:: Right. As to the album format itself, did you foresee that becoming a possible artistic statement for you? Did you connect with albums like [The Beatles’] Sgt. Pepper and [Pink Floyd’s] The Piper at the Gates of Dawn as album concepts in a way that hit you as a music creator?

Anderson:: Well, exactly! At that point, I was just 20 years old when The Piper at the Gates of Dawn and Sgt. Pepper were released [in 1967]. They were a signpost saying, “Progressive Rock — This Way.” Not that Sgt. Pepper was progressive rock — it was progressive pop. But Piper at the Gates of Dawn was something quite rich and eclectic in that early work of Syd Barrett as a lyricist and a tunesmith, so that was an important record too.

Albums were part of my life from my teenage years onwards, and trying to find albums by jazz and rock musicians was not that easy in the town I lived in. There was only one record store where you could go and actually listen to something — and if you liked it, you could save up your money, and buy a record you hoped you would get pleasure from.

Mettler:: What was the name of that shop? Do you recall what it was?

Anderson:: I don’t. I don’t recall the name of it, no. I know exactly where it was, geographically speaking, but no, I don’t recall the name of it.

Mettler:: Did it have those listening booths where you could actually go audition the records and put the headphones on, and all that?

Anderson:: Exactly. Exactly. Yeah.

Mettler:: Did you audition anything and then buy the album automatically, or did you just buy stuff on instinct?

Anderson:: No. [Early Jethro Tull bandmembers] John Evans and Jeffrey Hammond and I would go into the record store and persuade the long-suffering and kind shopkeeper to let us hear something that he and I knew we were probably never going to buy — but it was part of the experience.

Once in a while, we bought something. We would try and put a little money in, each of us, to buy some record by somebody who was important to us. It wasn’t chart material — it was definitely in the esoteric world of jazz and blues. I mean, you could buy pop records in Woolworths, so you didn’t have to go very far to get any of that.

Mettler:: Do you still have any of those records you guys bought back in the day saved somewhere, or did you not keep any of them?

Anderson:: No, I’m afraid I don’t have them. I think probably Jeffrey and John may have kept some records, but I don’t think I have anything from that era. Indeed, some of the music I listened to was replaced over the years when I could afford to buy a record or download something in later years, but I don’t have any of those [early] records.

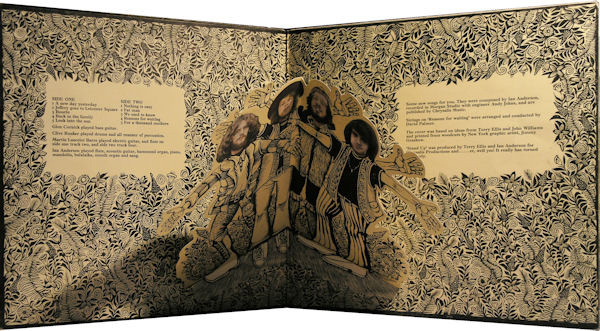

Mettler:: Understood. When Jethro Tull as an entity start making albums back in the ’60s, you took care to make sure we got a full album experience like we did with the Stand Up record [which was released in July 1969 on Island in the UK, and Reprise in the U.S.]. We can literally experience it as it unfolds right in front of us as we open the gatefold sleeve. Did you want that full kind of experience for your audience? Like, thinking about it in terms of, “Since we have this 12-by-12 format, I want the cover to be interesting. I want people to open it up and see things, and read things, and have a complete experience while they’re listening to the album.” Was that very important to you to present a complete album package?

Anderson:: I think what was very, very important to us was to get the album written and recorded in May [of 1969] before we had another tour that we had to go on (MM laughs) — and therefore, we were always working to deadlines, and working to try and achieve a result without really having too much objectivity, or time, to think about it along the way.

We were under a lot of pressure to get things done. And on the Stand Up album, for example, our manager, Terry Ellis, was the one who came up with the idea for a cover, and he commissioned an American artist [James Grashow] to produce a woodcut. The inside was a pop-up, sort of cartoon thing — which, yeah, I have to say. . . (slight pause), I mean, it was a good idea because it was different, and it got attention. I found it a little bit cartoon-like, personally, but it was a bit of fun.

It wasn’t my idea anyway. But the music was, and the learning process of working in the studio with Andy Johns — a young, untested engineer who had a lot of talent and also being the brother of Glyn Johns, who was a producer with The Rolling Stones. Young Andy Johns, his kid brother, was like us — full of enthusiasm about learning studio technique and making records. There was a good symbiotic relationship between him and me at a time when he was relatively clean.

Mettler:: Obviously, it was very important to have breathing as an element of RökFlöte, because we have these very deep breaths that both open and end the entire album as kind of like its literal bookends. Just to clarify it — is that your breathing at the beginning and the end of the record?

Anderson:: Well, yes. There’s nothing on the record that is a sound sample from other sources. No, it’s all stuff that was recorded. But, yes, it’s the breath of life at the beginning — the breadth of Ymir, bringing the universe into being. It’s the creator, which is common pretty much to all religions — a single creator force. So, yes, the beginning and end are essentially the birth and rebirth, due to the primal force.

Mettler:: I get it. Whatever the God concept means to people, you have it covered in the broader sense with that breath at the beginning, and that breath at the end.

And breathing, in general, means a lot to Jethro Tull music because, to me, hearing it acts like a sense of space. You know how to keep your arrangements open, and I always like the fact that we often hear you take breaths when you’re playing the flute. Some people get clinical about those things, and then we never hear the humanity in the playing in certain recordings. But you seem to always make sure we can hear the character of how you’re breathing — or you make sure it’s a heard sound and you keep it all quite lively, which has to be important to you just to get the character across in what you’re playing.

Anderson:: Well, it’s something that I do actually spend a bit of time with, because — in the past, in the early days of digital recording — I made a point of tidying things up and editing out the breaths, and particularly when playing the flute, to try and keep it more transparent and clear.

But then I thought, “You know, this just doesn’t sound right.” So I’ve spent a lot of time actually just getting the right amount of breath. I don’t want any extraneous noises beyond that. But I usually try to find — if I’m editing, for instance — two separate takes of a vocal together. I’m really careful about where that edit is, because I want to hear the breath sounding natural. Even if, maybe in the context of all the music, you don’t really hear it, but I like the idea that I try and keep it natural, both for playing the flute and singing. I do retain the essential elements of breath because it does — in a subliminal kind of a way — inform you of the performance and the nature of actually singing.

But there are some records I know where I hear people breathing, and I hear other noises — and it’s actually a little obtrusive. You really do have to spend a bit of time to find the right balance of where hearing breath — the intake, and the exhalation — has got to sound natural, and believable. So I do pay attention to that, yeah.

Mettler:: Let me give you a broad question to wrap things up. I want to jump us 50 years into the future, where it’s now 2073. Probably neither you nor I are physically on the planet unless there’s some science thing that keeps us here. So, however people are listening to music in that year, and they type in “Ian Anderson” or “Jethro Tull” into however they listen to music in that future, what do you want them to get out of that experience?

Anderson:: I suppose it would be nice to think they might get 10 percent of what I get out of listening to Bach or Beethoven, or Mozart or Handel. And if we’re talking 50 or a couple of hundred years down the line, then I think I’d be very, very disappointed of the music I’ve been a part of in the contemporary age — the whole history of rock music — and that’s realistically about 60 years’ worth of what we would call rock music, generally speaking. But, from the point where rock music became a serious thing from the beginning of the ’60s onwards, then I would say, just to be part of that era was great — and I’d be very, very upset to think it wouldn’t be listened to in the future.

I don’t know that there’s any illusion it’ll be remembered with the importance of the great era of classical music — which, the more you acquaint yourself with it as you do with classical painting and classical writing, then you do come to recognize the enormity of human invention and the originality of human invention, compared to the imitation and the mental copying and pasting that goes on in the creative processes today. Only once in a while does something pop up and say, “Hey — I’m different from those other guys.”

There’s so much rock music that it’s difficult to imagine people will necessarily be able to hear everything. They will prioritize — or others will prioritize for them. That far down the line, there might still be some reference to Jethro Tull, but it might just be a few tracks bundled together as a little historical example of something — I don’t know, but I would like to think someone would derive something from it.

And, as I said, if they got 10 percent of what I get out of listening to great classical musicians — or indeed, sometimes to something more contemporary from the world of jazz or folk music — then I would be very pleased with that.

JETHRO TULL

RÖKFLÖTE

180g 1LP (InsideOut Music)

Side 1

1. Voluspo

2. Ginnungagap

3. Allfather

4. The Feathered Consort

5. Hammer On Hammer

6. Wolf Unchained

Side 2

1. The Perfect One

2. Trickster (And The Mistletoe)

3. Cornucopia

4. The Navigators

5. Guardian’s Watch

6. Ithavoll

Truly an icon.

In Iceland, my nickname when I was a teenager was "Hönd Flöte."

This is very tough. I apologize for a sort of cliche answer, but Aqualung and Thick As A Brick were a potent one-two punch for me as a wayward youth.

Then, I faded quickly on War Child but that is my wife's and her younger brother's favorite (along with Songs From The Wood): so I admit there may be a certain age of 'imprinting' favorites when we first get acquainted with a band.

Crest of a Knave and Passion Play are up top, as well, and I like Stand Up alot...so color me a 1969 to 1975 blurred all together fan, except War Child.

(War Child seemed compressed, I always thought Bungle in the Jungle lacked dynamics, even as a kid.)

I think Jethro Tull is the collective favorite band for my my wife and her five siblings. They know all the words! Any time a Tull song pops up at family gatherings, it turns into a giant pandemonious family karaoke that I marvel at and watch their sheer joy.

Cheers!

Man, the first time I heard the intro into the 'fanfare' of Locomotive Breath....it was simply stunning. I get nostalgic for that feeling, beyond the music itself. It was a holy crap moment. (Even that could use a little less compression, but that's a pet sonic peeve of mine.)

As a Tull fan starting with the very first album, I'm always interested in Anderson's take on his own work, and music in general. He's one of a kind. Just one thing I'm curious about...seven different colored LPs? Really? Why? Is anyone enough of a hard-core follower to buy all of them? I guess there might be a few who will do that.

Great reading Ian's perspectives... will be looking forward to catching up on his newer albums... last one I dove into was TAAB2 so its been a while.