What a valuable and great interview this is!

Of course, I remember when George Winston and Windham Hill were in the air everywhere. The early '80s, I guess, though I definitely remember a late 80s-early '90s vibe, too, since Winston was adjacent to the "cool Jazz" format that was popular during those years. (At least, here in New York City, it was.)

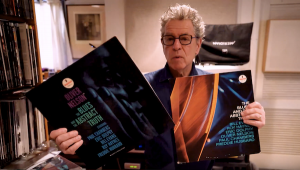

This interview tells me all the things I never understood about Winston. Of course, I noticed the quality of the recordings at the time. But it's interesting to hear the details from him, and also to learn that he essentially created a genre of music which I at one time mistook for noodling elevator music.