The SHF album didn't come up in this interview, but I happened to play it just two days ago. It wasn't the blockbuster success it was supposed to be-some say the three writers were saving their best material for solo albums-but I like it quite a bit. The original LP sounds terrific, while the only American CD version available is one of the worst-sounding CDs ever produced. RIP JD Souther, quite a talent, a gentleman, and a guy with a lot of good friends.

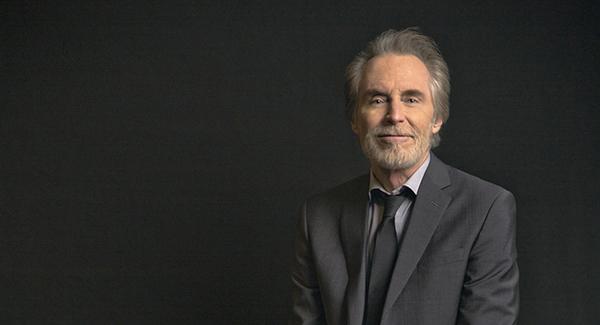

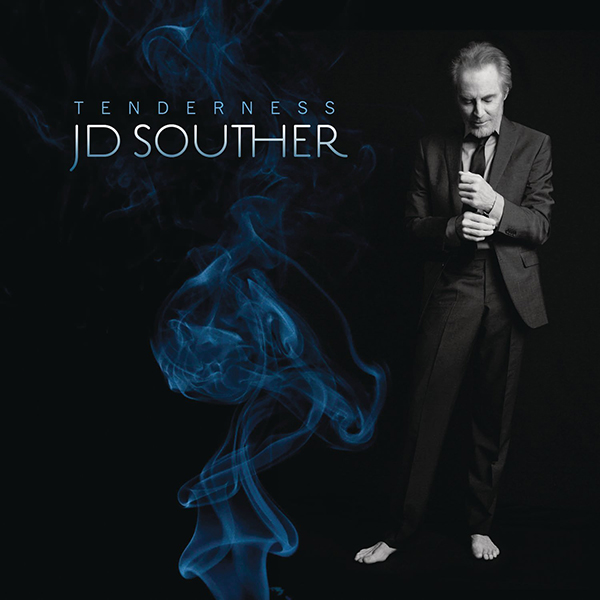

RIP JD Souther: A Consummate Songwriter Talks About Buying Turntables, Mastering for Vinyl, and His Indelible Collaborations with Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, and Roy Orbison

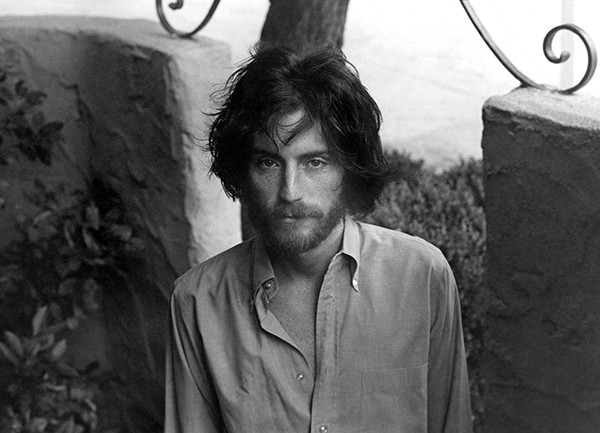

JD Souther, a consummate American songwriter known for co-writing hits and choice deep cuts for (and with) the Eagles as well as for his poignant collaborations with James Taylor, Roy Orbison, and onetime life partner Linda Ronstadt, passed away at age 78 at his home in New Mexico on September 17, 2024.

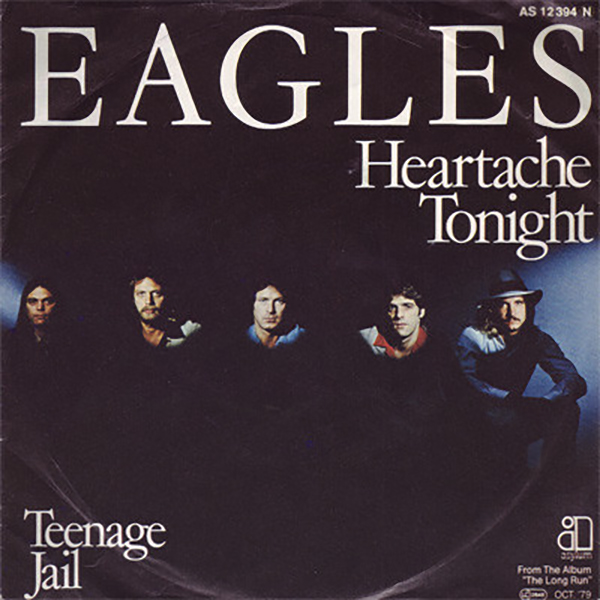

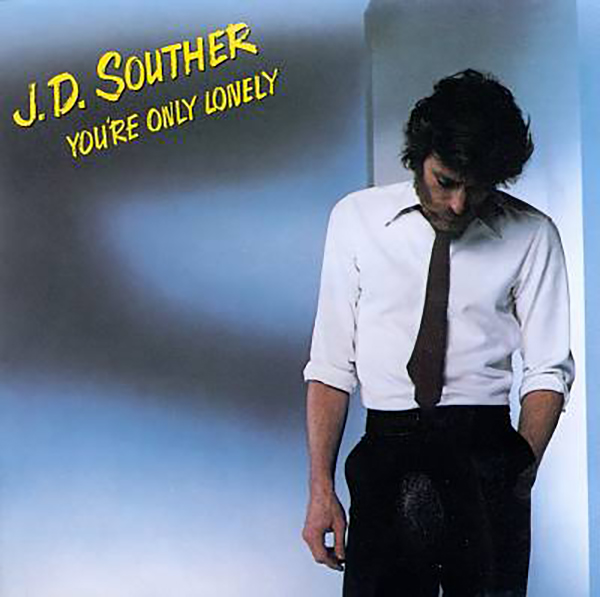

I have so many favorite “JD Moments” on vinyl — and I bet you do too. Among them are immortal Eagles cuts like “How Long,” “James Dean,” “New Kid in Town,” “Victim of Love,” “Heartache Tonight,” and “The Sad Café.” During his time working with Ronstadt, there’s “Faithless Love,” “Prisoner in Disguise,” and “Hearts Against the Wind.” Then you’ve got his 1979 solo single “You’re Only Lonely,” plus his 1981 duet with James Taylor “Her Town Too,” and latter-career solo LPs like May 2011’s Natural History, a revisitation of a number of tracks he penned for himself and other artists over the years, on Slow Curve Records — all of which, in their own ways, evinced his embrace of the joys of listening to and being aurally rewarded by music via an analog format.

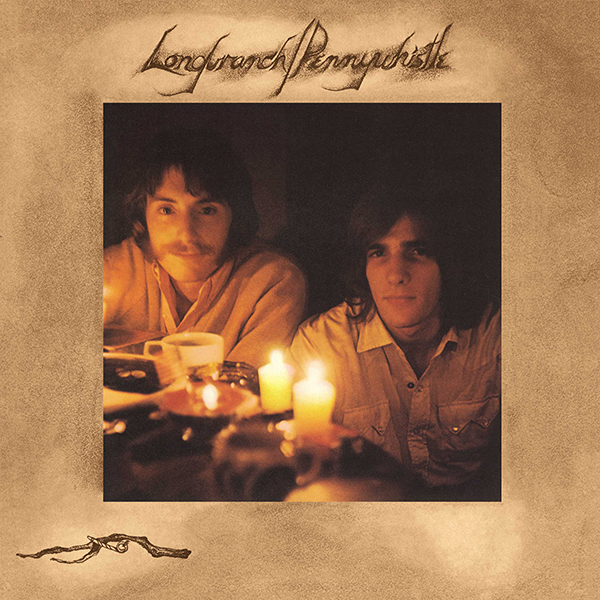

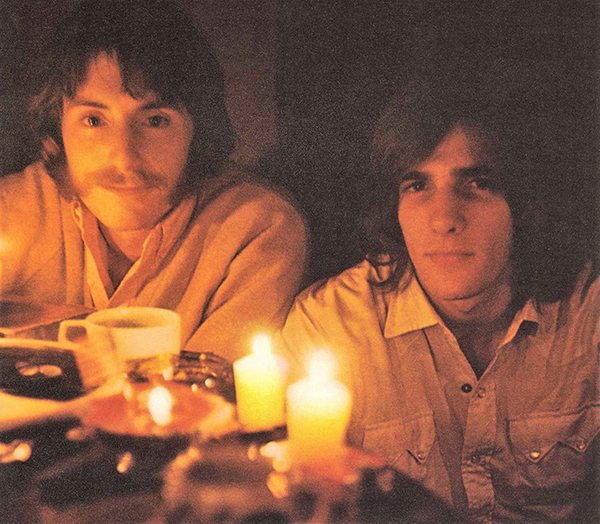

All that said, Souther first planted his roots with Longbranch/Pennywhistle, the self-titled 1969 LP on Jimmy Bowen’s Amos Records imprint that was the initial on-record collaboration with his longstanding songwriting compadre, the late, great Eagles co-founder Glenn Frey. Embedded within the ten tracks that comprise Longbranch/Pennywhistle are the secret sonic salve and song-construction building blocks upon which successive generations of singers and songwriters have drawn California-countrified inspiration, known or otherwise.

Indelibly stamped songs like Frey’s cautionary jailbait tale “Run Boy, Run” (Side 1, Track 2) and the tenderly sweet harmonies permeating “Rebecca” (Side 1, Track 3) are juxtaposed alongside Souther’s yearning ode to the idealized yet calculating “Kite Woman” (Side 1, Track 5) and the sociopolitical tsk-tsking of “Mister, Mister” (Side 2, Track 2), and they all helped sow the seeds for a style of American-bred music that continues to grow and reach new and old audiences alike to this very day.

Long consigned to the cutout-bin tumbleweeds, Longbranch/Pennywhistle finally got its proper reissue due thanks to Geffen/UMe’s 180g 1LP edition that was released in October 2018, as remixed by producer/engineer Elliot Scheiner (Eagles, Steely Dan, Toto) and Souther. Originally produced by Tom Thacker, Longbranch/Pennywhistle boasts an impressive C.V. of ace collaborators including rockabilly guitar legend James Burton, slide maestro Ry Cooder (credited here as “Ryland P. Cooder”), pedal-steel legend Buddy Emmons, Wrecking Crew pianist Larry Knechtel, session drummer Jim Gordon, bass master Joe Osborn, and fiddle player nonpareil Doug Kershaw.

“It’s got a certain charm to it,” Souther demurred to me about the S/T L/P LP with a wry chuckle during one of more than a few phone interviews we conducted together over the years — before adding, “even if it still sounds like an 8-track record from guys who didn’t write that well working with first-time producers.”

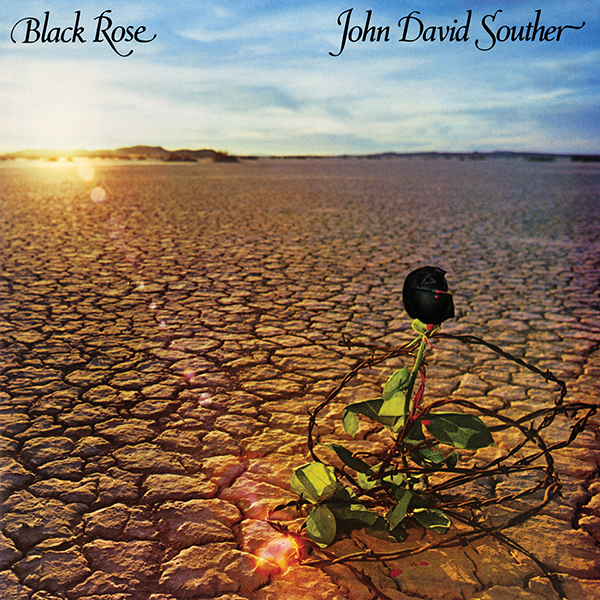

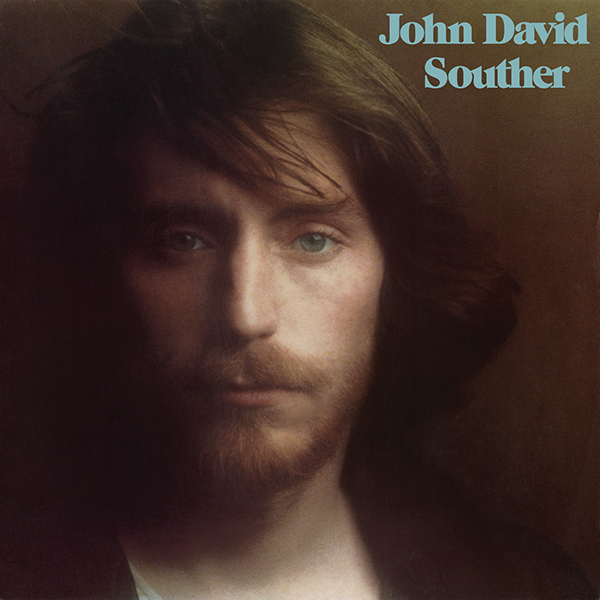

Souther was a master visual songwriter/storyteller, and when he oversaw a 180g 1LP reissue series of a trio of his early solo albums through Omnivore in 2018 — 1972’s John David Souther, 1976’s Black Rose, and 1984’s Home by Dawn — he had quite the clear picture (pun intended) of his initial intentions for them. I told Souther that, after listening to all three reissued LPs back-to-back, I wholly agreed with his liner notes statement that went, “I try to design every one of my albums to sound different than the one before it. If you’re making a movie, you’re not making the same movie.” Souther concurred with that assessment, telling me in response that, “Yeah, they really are different. Until we started on this [reissue] project, I never had to listen to these albums all so close together. And I definitely got what I was after — which was a different movie every time.” (Seeing/hearing is believing.)

A truncated version of one of our interviews appeared over on our sister site Sound & Vision back in the day, and I also wound up compiling a somewhat extended version that posted on my own SoundBard site. Not long after I learned of Souther’s passing late last night, I dug out my original interview transcriptions to enhance the analog-centric depth of the content that follows. Here, Souther and I go deeper than deep to discuss his appreciation for good turntables and mastering for vinyl, how long it took “New Kid in Town” (one of the hit Eagles tracks he co-wrote) to finally come to full fruition, and what artists/producers must do to make “great” vinyl masters. There’s talk on the street, it’s there to remind you / They will never forget you ’til somebody new comes along. . .

Mike Mettler: Let’s get right into vinyl. Is that the way you personally listen to music the most?

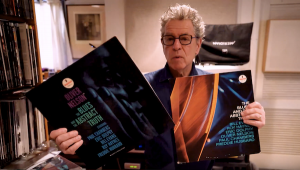

JD Souther: If I can get what I want to hear on vinyl, then yes. Fortunately, I didn’t throw any of it away. I’ve got a lot of vinyl.

Mettler: Me too! (both laugh) What kind of turntable do you have?

Souther: I had Audio-Technica as a sponsor for years, so I bought a lot of Audio-Technica stuff. (chuckles) And I had two Luxman turntables. In the guest house, I still use a big Luxman amp and tuner, and there might be a Luxman turntable over there somewhere.

But Audio-Technica gave me such great microphones, and they gave me some of their turntables too — which, by the way, are really great, and go for a reasonable price. I always encourage people at gigs to go to an independent record store and buy a turntable. They go for much less money than they had before. And if you can be bothered to go get a cartridge put in, they sound as good as the old expensive ones used to.

Mettler: I’m with you on that. I had to get the right cartridge for my reference turntable when I first bought it, and I’m glad I did. I can’t imagine dropping anything else down on any records I spin on it.

Souther: You know something? It’s so critical. When I got the vinyl copies of Tenderness, the album I put out on Sony Masterworks [in May 2015], I thought, “This isn’t quite as great a pressing as it should be.” It was done by Bernie Grundman, one of the last great artists of mastering, and my producer Larry Klein was there for the cutting of it. These guys can’t think this is pretty good, and me think that it’s not. Sure enough, it was me using a faulty needle. I swapped it out, put it back on, and went, “Oh my God, this sounds great!”

The strings just sound wonderful on Tenderness. You have to hear them on vinyl — it’s a revelation. Larry told me after he heard it, “I’m not going to say anything. Just go home and put on the beginning of the record and hear how it starts, with the string section.” [Hear it for yourself on said lead track on Side One, “Come What May.”]

Mettler: That opening really breathes on vinyl, absolutely. What kind of speakers do you have in your system?

Souther: I have four sets of speakers. What I listen to almost all the time I’m almost embarrassed to tell you — they’re the same JBL 4310s Linda [Ronstadt] and I listened to when we were living together. I also have some JBL 4311s and some Tannoys, Genelecs, and Yamahas, but the ones that I really like are these big, warm 4310s and 4311s.

Mettler: I can understand that, because if you like a particular speaker and its sound, you tend to stick with it — especially ones like those JBLs, which were built to last.

Souther: They were definitely built to last. They’re wonderful, and they’ve definitely got that deep midrange too.

Mettler: People like to say your musical style is “Americana,” but knowing your background and how jazz is important to you, plus the classical music and opera that was in your house while you were growing up — all of that was in the cauldron and behind some of your songwriting, I think.

Souther: Yes, definitely. It was just the synthesis of everything I had heard at the time, combined with the fact that I was just learning how to play guitar.

Mettler: That’s right — you didn’t pick up a guitar until you were like 23 or something.

Souther: Yeah, first I was a drummer, and a jazz violinist.

Mettler: But you can’t carry drums on a Triumph motorcycle, as they say — or as you said back then.

Souther: And it requires juggling skills that I don’t have. You know, we didn’t have much more room when Glenn Frey and I were going to gigs together in my Sunbeam Alpine [in the Los Angeles area in the late ’60s and early ’70s]. We basically had room to barely stack one guitar behind each seat if we pulled the seats all the way forward.

Mettler: I was so sorry to hear about Glenn’s passing. That must have been tough. [Frey, to the right of Souther in the L/P duo photo above by Mark Creamer, passed away on January 18, 2016, at age 67.]

Souther: Tough loss. Yeah. We always said we’d write ’em to last. And they seem to have lasted so far. We’ll see.

Mettler: How satisfying is to you to have people experience, or even re-experience, that long-lost Longbranch/Pennywhistle record?

Souther: Very. When I heard the test pressing, it sounded pretty good to me. Elliot [Scheiner] did a pretty good job. I mean, he did what he could with it. It was a poorly recorded album to begin with. It was on 8 tracks, and they [i.e., the original label and producers] did some really weird things with it. Like, they locked the bass and the bass drum on the same track. And that was something we really couldn’t un-do, you know?

There was another dumb thing with two other instruments locked on the same track. But they didn’t have any idea what they were doing. We were only there for a few days with the producers. When Elliot went to mix it, he was like, “Man, I’m doing the best I can, but I think we just give it our best shot and play to historical accuracy here — it’s 1968. If we try to make it sound like an ’80s or ’90s or a modern record, it’s going to be cheesy, so let’s just go with what we have, and I’ll try to be as authentic as I can.” Even so, I think we each have one good song on the record.

Mettler: Let me guess. For you, it’s gotta be “Kite Woman,” since you also recut it for your first solo record [1972’s John David Souther, on Asylum], right?

Souther: Probably, yeah. Although “Mister, Mister” is a pretty good song too.

Mettler: There are a couple of interesting lines in “Mister, Mister,” especially when you listen to how it applies to the here and now, 50-plus years later. The line I’m thinking of is, “You say men are born in anger / to be cruel is to be strong.” And isn’t that the thing about a great song? It’s going to have a shelf life beyond the moment you originally had the idea for it. The other thing is, yours and Glenn’s voices blended so well together on this album — but they always did, really.

Souther: Really well! But his voice was much better than mine — probably always was. Glenn sang softer than I did, and I sang further from the mike and louder, which means thinner.

Mettler: You’re way upfront in the mix. On Side 2, you also take centerstage.

Souther: Yeah. On Side 1, Glenn’s more up in the mix. It’s a little erratic, but we’re on the same mike, and we’re just fooling ourselves. We balanced it just like we would onstage, but eventually onstage we wound up singing on separate mikes, just because our guitars kept banging into each other. (MM laughs) And I don’t think I sang very well on that album, except on “Mister, Mister.” I think it’s because it was so quiet on that song, that I wasn’t singing too loud.

Mettler: Actually, it reminds me a bit of Jesse Colin Young’s “Darkness, Darkness” [from The Youngbloods’ third studio LP on RCA Victor, April 1969’s Elephant Mountain], and the way he handles the dynamics there.

Souther: Ooh, that’s one of my favorite records. I think one of the definitive records of the late ’60s is another song of his (half-sings): “Come on people, now, smile on your brother. . .” [That’s a line from, of course, The Youngbloods’ Young-sung “Get Together,” originally released on their-self titled RCA Victor LP in 1967 and later re-released in 1969, when it became a national Top 5 hit.]

That’s a magical record, man. When that record starts, the whole room lightens up. The first time I heard it in New York, I went, “Wow! This guy has tapped into something so beautiful, and so simple, and so elegant.” He had a gorgeous voice, and it does have that warmth. It’s just empathetic to everything. [You can read my recent interview with Jesse Colin Young that posted on July 10, 2024, over on our sister site Sound & Vision, right here.]

Mettler: And now here we are, past the half-century mark of Longbranch/Pennywhistle. Is it easy to give a broad-sweeping legacy statement about it from the surviving half of the creative team, or is that too much weight to put on you? (chuckles)

Souther: That’s too much weight! (chuckles) Well, I have one bit of advice: Don’t over-sing. If you have some confidence in your melody, just sing the melody. I don’t have any critique of that album. I wish we had more time to do it — and to do it with 16 tracks instead of 8, or even just have had a little bit better organization in the studio. That whole album was thrown together quick with no rehearsal, and it was cut and mixed in 2 days.

That said, I think we did pretty well with it. We were just new at songwriting back then, and I think Glenn actually took more time with his songs than me. That’s why “Rebecca” and “Run Boy, Run” sound really complete, and concise. The two I took the most time with were “Kite Woman” and “Mister, Mister,” and those are the two that sound more mature to me and more complete, and less dependent on licks or flourishes.

Mettler: That’s some good detail-memory, JD, so there must be something special about the album that still sticks with you.

Souther: My memory is an ever-changing patchwork of pieces that don’t necessarily fit with each other. Sometimes it’s photographic, other times it’s completely (brief pause) . . . missing. (both laugh)

Mettler:You and Glenn were very meticulous in terms of songs and word choices. Would you agonize over them for a period of time? Tell me a little about that from the songwriter’s point of view.

Souther: We did that for weeks — months! (chuckles) Yes.

Mettler: Is there one line you can cite that took you weeks to figure out, but when you hear it now, it sounds like it came easily?

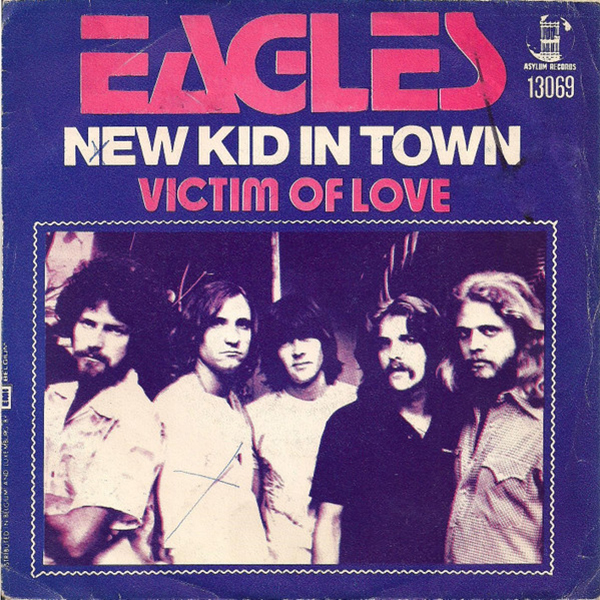

Souther: Umm, it’s more like decisions about how to proceed with the story. Fine-tuning the lines — I don’t think anybody really remembers who did what. But I can tell you when some things happened. I know I had the chorus for “New Kid in Town” for about a year before Don [Henley, Eagles co-founder] and Glenn heard it — and I couldn’t think of a thing to do with it.

But it was time for a new album, so we convened at Glenn’s house, as we often did. We sat around his sort of picnic table/dinner table and threw out the legal tablets and pencils. I played him that one and he went, “Yeah! Okay, that’s a good way to start the album. It’s a good first single.” I think we spent, geez, a year on that song.

Mettler: Wow. And that’s not a short song, either. It clocks in pretty long for what people considered for singles then, but you don’t really notice it. [The "New Kid in Town" single clocked in at 4:49, cut down from 5:09 on the December 1976 Hotel California LP on Asylum. The song hit No. 1 on the Billboard Top 100 singles chart on February 26, 1977.]

Souther: All of ours did! That’s why “Best of My Love” [from March 1974’s On the Border, also on Asylum] was not released as a single at first. It was too long, and it had steel drums and no guitars. It wouldn’t have a chance on radio. [The album version of “Best of My Love” is 4:34; the single version was cut to 3:25.]

Mettler: And look what happened — it too became a No. 1 single! Sorry, Ma! [“Best of My Love” hit No. 1 on the Billboard Top 100 singles chart on March 1, 1975, almost a full year after On the Border was released.] It just goes to show that the story wins. And the way ”New Kid in Town” unfolded especially rang true to those of us who moved around a lot as youngsters. You could relate to how that story went — right until somebody new came along, to borrow a line.

Souther: Yeah, that’s it: “They will never forget you ’til somebody new comes along.”

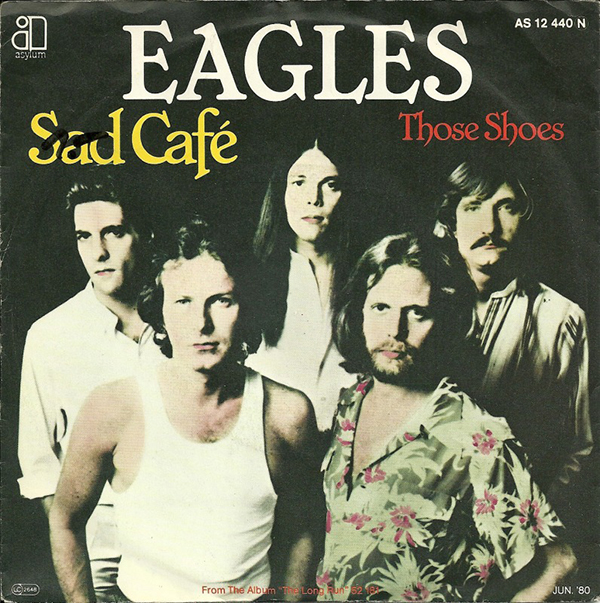

Mettler: I like songs that unfold like that, just like the way “The Sad Café” does [from the Eagles’ September 1979 album on Asylum, The Long Run]. You look at the time read out on that [5:35], but it doesn’t matter because you get lost in the storytelling.

Souther: That’s a pretty epic situation, and there were four writers involved there [Souther, Don Henley, Glenn Frey, and Joe Walsh]. That was really us talking about our lost innocence.

Mettler: You were living through things people really hadn’t before in the post-War era, and then writing about them.

Souther: Also, the first of our friends were starting to die off — from drugs, car accidents, and various things. It was an eye-opening time. We spent a lot of time in that restaurant at the back table there, just talking about our lives, what was going to become of us, and what had become of some of us. It’s an interesting song. It’s an autobiographical song written by four people.

Mettler: It seems to have a lot more resonance now, considering all those who’ve passed away recently. You feel it even deeper.

Souther: (slight pause) Well, every time one of the tribe leaves the fire, everybody has to move in a little closer.

Mettler: I’m glad we have this music in the world, at least. Speaking of four songwriters, there were also four of you credited on “Heartache Tonight,” which seemed to come together in an interesting way. [The four writers for “Heartache Tonight,” which also appears on the aforementioned The Long Run, are Henley, Frey, Souther, and Bob Seger.]

Souther: (chuckles) Yes it did. Glenn and I started it, and it was fine. We were standing around my house listening to Sam Cooke records. It started the way the record does — we had the guitar intro and were clapping our hands and singing the stuff, but we couldn’t think of a chorus, the way to get back to the verse again. I was on the phone with Bob Seger and I sang it to him, and he said, “Well, how about this?” And he sang the chorus.

You take it from anywhere it comes. We were all friends, we all sang, and we had a similar interest in making things sound as good as possible. Actually, Glenn called me and asked, “How do you feel about having four writers on this song?” I said, “Well, that’s a lot of ways to split the money, but it’s really good. Really good.” (chuckles)

Mettler: I was a kid growing up in a Pittsburgh suburb, and I remember the first time I heard "Heartache Tonight" on the radio. You could sing along with it right away. As a listener, you just clued right into that song instantaneously.

Souther: That’s nice to hear. It was designed to be a catchy tune — a summer kind of feel-good song. [“Heartache Tonight” was released as a single on September 18, 1979 — 45 years ago to the day of this post! — and it hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart almost 2 months later on November 10, 1979.]

Mettler: Well, mission accomplished.

Souther: Yeah, I’d say! (both laugh)

Mettler: Let’s get into your solo LPs. I agree with what you said about the John David Souther record [released on Asylum in 1972, and reissued by Omnivore in 2018] in terms of there being a clarity of tone and space, something I think is lacking in many modern recordings. You need to allow certain words and phrases to breathe across the different bars, and not have everything “hit” you full-on all of the time. You set a nice template in ’71 and ’72 for that kind of style.

Souther: Thank you. Well, Miles Davis always said the space between the notes is just as important as the notes. Space — space just works. I don’t critique one particular era of music over another, but I think one thing that is problematic now sometimes is, especially with pop music, there’s absolutely no space left in the records. It’s just thing upon thing upon thing. Every vocal is doubled and processed and harmonized. It’s a little exhausting, and it doesn’t really give you time to absorb what’s happening. People might argue with that and say not much is happening that’s truly musical (chuckles), but you might not know it if it was anyway. There’s so much production crammed into all the nooks and crannies.

I remember when you’d end up with 12 boxes of tape on the floor that you’d have to sort back through and cut. And there was a period of time where tape quality became very inconsistent. There was such low demand for it that a lot of tape manufacturers went out of business, and what was left was erratic in quality. Now that there are more people doing things analog, tape quality is more consistent again. But if you want to cut with analog tape, you have to prepare yourself for a lot of work if you’re going to cut things together and overdub them. And, of course, you have to be careful about that too, because tape decays.

Mettler: That’s true. Tape is a medium that deteriorates.

Souther: When we were putting these [Omnivore LP] reissues together and looking at these old tapes, we had to cook ’em a little first before we could play ’em. Everything we do that’s new, we do in the highest resolution possible, because the goal is to make a great vinyl master. All of my new records since 2008 have come out on vinyl. They’re mastered for vinyl, and they’re 180-gram. They sound wonderful. They certainly sound better than the CDs, and especially better than the downloads.

Mettler: No arguments here. You included some demos and works in progress on these reissues. When you were going through the original tapes, did any song reveal itself to you differently, listening to it 40 years or so later after you recorded it?

Souther: Well, they all did anyway, whether they were on the release master or coming out of the vault and being something I hadn’t listened to for 30-plus years. It didn’t matter at all. They all do something slightly different than they would have when I was in the heat of finishing them. I think it’s pretty amusing, actually. I had a lot of fun. We listened to them a lot while we were assembling them.

Mettler: Another one of your collaborators I spoke with is one who has golden ears — Linda Ronstadt. [You can read my interview with Linda that posted on May 28, 2014, on Sound & Vision, right here.] I think you once said something like, “you need to be a great listener to be a great musician” — and that certainly applies to Linda, wouldn’t you say?

Souther: She’s the best listener I know, yeah.

Mettler: Something she mentioned to me was, after you had read her book [Simple Dreams, published by Simon & Schuster in September 2013], you called her and talked about the B-29s that flew overhead in Tucson [Arizona]. Could you tell me that story from your point of view?

Souther: They lived close to an Air Force base too. I grew up in Amarillo, Texas — which is also outside an Air Force base — and she made reference to Nelson Riddle and how the charts he had written always had this great “hum” in them. It’s not bass like a subwoofer — it’s just a real hearty, cello-range, upper-bass-range strength that was there. And she said it reminded her of the planes that were taking off from the air base near her when she was growing up. I reminded her that B-29s flew during World War II, so that’s probably not what she heard.

But we had a few of them in Amarillo too, and I actually tried to figure out what the notes were with the B-52s and other various planes that took off. I couldn’t figure it out, and she finally said, “Well, I don’t know what the frequencies were. It was just the feeling that was always there on Nelson’s charts.” He was one of the great arrangers of our lifetime. [Riddle passed away at age 64 in 1985.]

Mettler: I think it was the fourths and fifths, is what she said. You grow up with certain sounds, and they just get ingrained into your songwriting. You had a jazz background, like we talked about before, and the clarinet was one of the earliest instruments you played.

Souther: It’s true. First I played violin, then I played clarinet. I started to play tenor sax, but it was a little big for me. I went to clarinet in the 5th grade. I was a pretty small kid in high school, so tenor was a little bit ungainly for me. But they also needed a clarinet player. It’s the same key and the same fingering, so I learned that. I moved over to tenor a little later, and I was quite happy with that until I discovered drums. And I went, “Ah hah! This is where I must be.”

Mettler: Is there a particular favorite album of Linda’s that you still put on the turntable?

Souther: My favorite stuff that Linda ever did were the three albums with Nelson Riddle [September 1983’s What’s New, November 1984’s Lush Life, and September 1986’s For Sentimental Reasons, all on Asylum]. Those three records are just magnificent. She really studied that material for years, and we talked about it for a really long time. I remember the record company thinking it was a bad idea at the time, and she had people going, “Hey, you’re a country rock singer!” I remember saying to her, “No, you must go for this! You gotta do this!”

When we were together, we listened to those [Frank] Sinatra and Nelson Riddle records all the time. And I think she did a great job. Actually, in the car coming home from dinner last night, I was listening to her version of “Skylark” [written in 1941 by Johnny Mercer and Hoagy Carmichael and recorded by Glenn Miller and His Orchestra in 1942; Linda’s version on Lush Life was nominated for a Grammy]. Absolutely magnificent. I’m on the record for wanting to see everything of hers re-released in the highest quality possible.

Mettler: She and I talked about that too. Cry Like a Rainstorm, Howl Like the Wind [originally released in October 1989 on Elektra, and recently reissued in 2024 on translucent blue vinyl by Iconic in recognition of the LP’s 35th anniversary] was recorded at the Skywalker Ranch, and she had to make sure it was done up to that standard. It’s one of the best recordings she’s done, studio-wise.

Souther: I think when she was recording up there, George Massenburg was engineering, right? There’s no more meticulous human being alive than him.

Mettler: Yes, he was. That was a perfect marriage there. Your parents played a lot of music in the house. Is there one record you’d consider to be the first one you clued into personally, on your own?

Souther: I first started buying rock & roll records when I had a paper route in the 7th or 8th grade, but the first record that I remember buying that absolutely killed me — I’m sure they were either Ray Charles records, or The Everly Brothers. I feel that Ray Charles is the most important musician of the second half of the 20th century. He changed everything about music. He played fantastic R&B and a lot of churchy-gospely stuff, and then he had huge rock & roll hits, and he made great jazz. He and Quincy Jones were partners, and the charts for those records were amazing. He also did incredible standards. When he put out the Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music [in April 1962 on ABC/Paramount, which was later reissued on 180g in 2022 by Second Records in recognition of the LP’s 60th anniversary], he pretty much conquered the world.

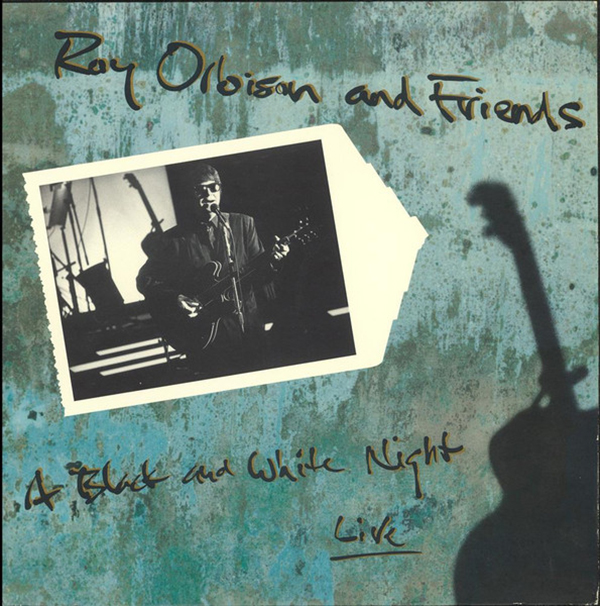

Mettler: He sure did. And somebody else you worked with later in life, Roy Orbison, must have also been a huge influence at the time.

Souther: He was most definitely an influence. He was a beautiful singer, a beautiful guy, and the songs are absolutely flawless. And the records are good too. They really made astonishingly good records. I got to know him later in life. Just amazing.

Mettler: How spot-on was his voice while you worked on A Black and White Night – Live together [in 1987, and released in 1989 on Virgin]?

Souther: I’ll tell you what — it was still damn good after 40 or so years of singing on the road and in clubs. Yes, he still had a gorgeous, gorgeous voice, and a lot of range. He had a great feel for music. He was a delightful guy. Fun to write with, fun to sing with. I hear him in all of us.

Tom Petty told him once when they were working on The Traveling Wilburys record [Vol. 1, released in October 1988 on Wilbury Records], “You might just be the best rock & roll singer in history.” The story is, he said (affects Orbison drawl), “Well . . . you might be right.” (both laugh) I don’t know if that’s true or not, but he was awfully good.

Mettler: I saw Bruce Springsteen in New Jersey a few years back [on January 31, 2016], and when he sang the line, “Roy Orbison singing for the lonely” [in “Thunder Road”], I felt a nice thread among the three of you. It made me think about your Top 10 1979 solo hit “You’re Only Lonely,” which does have a bit of a Roy feel to it. It all rolled together there in that one moment. [It’s the title track to Souther’s 1979 solo LP on Columbia — which was just reissued by Omnivore on July 26, 2024, and that LP can be ordered via Omnivore directly here, as well as via the Music Direct link graphic the very end of this story.]

Souther: It does have that kind of Roy feel to the song, yeah. After it came out, Roy told me his wife Barbara parsed every line of that song, looking for something. And he kept telling her, “Barbara, you’re not going to find anything. It’s not the same.” What is the same is that drumbeat is the same as another Roy record called “I’m Hurtin’” [released as a 45 in 1960, on Monument]. It has the same kind of breaks in it.

Mettler: It just goes to show what’s in a songwriter’s DNA gets amalgamated into bits and pieces that then become an original thing — in your case, that JD Thing, as I’ll call it. (Souther laughs) Well, to bring it all back to you to wrap things up, having that three-record arc of your solo career back on vinyl must be refreshing — I mean, to enable people to access this music all at once. For a while, it was almost impossible to do that.

Souther: It really is satisfying to have it all there, and to see people be able to react to it in such a short time. I love it.

Mettler: And two of the title tracks are examples of two different styles of your playing. They encapsulate the breadth of how you record. I like the subtlety of “Black Rose” and how it ends with those great harmonies, and then the ’80s rockabilly sound of “Home by Dawn.” You defined an era of individual style before your time.

Souther: Well, I never really do know where I’m positioned in time. I just tried to make records that sounded interesting to me that I’d never heard before.

- Log in or register to post comments

the opening song on that first SHF album, Furay's "Fallin' In Love". It sounds exactly like a great, lost Poco track. BTW, Poco was the first big concert I ever attended.