When I read "V2 CD" at the end of point number two, I thought rather than behind you, Satan had gotten inside of you :) What CD player do you have if I may ask?

Analog Corner #122

“Records? You want to talk about records? I have at least 7000 and you can have them! But you can’t come over and cherry-pick what you want. You have to take them all,” said the gent who’s sat next to me at Avery Fisher Hall for the past four years. Somehow, the subject of LPs hadn’t come up till then, maybe because he shows up at every New York Philharmonic concert with a bag full of CDs from Tower Records.

When I explained that many of his LPs might be valuable, he said, “If you keep them and enjoy them, that’s your business, but if you sell any, we split the money. How’s that?”

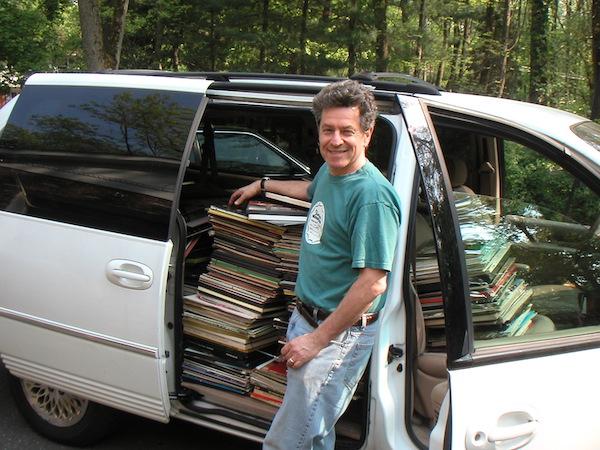

That was fine with me. So one Saturday a few weeks ago I drove down the Garden State Parkway in a minivan with my friend Nick. We hauled away 7000 classical LPs, most of which appear to have never been played. Few evinced spindle marks on the label, fingerprints on the surface, or even dust—nothing to indicate that they’d ever been removed from the inner sleeve.

The collection was built on great musical performances, not on audiophilia, so the representation of Mercury Living Presence, RCA Living Stereo, and the like was proportional to the percentage of great performances, not the percentage of great-sounding recordings on those labels. There were plenty of EMIs, some Deccas and Lyritas, and some awesome 45rpm Nimbuses, but who cares? This was a lifetime or two’s worth of amazing music, carefully collected, that I’m sharing with Nick, a 22-year-old senior at the Berklee College of Music who’s big into hard-core punk rock, free jazz, classical—and vinyl. “I’m all about the vinyl,” is how he puts it.

When I suggested we sell some of the records because we can’t possibly listen to them all, his said, “Come back in 20 years and I’ll tell you what’s left to play!”

The Graham Phantom materializes

The Graham Engineering 1.5 tonearm, originally introduced in 1990, was a thoughtfully executed design that logically addressed all of the basics of good tonearm performance—geometry, resonance control, rigidity, dynamic stability—with effective, sometimes ingenious ideas, while providing exceptional ease and flexibility of setup. Over time, designer Bob Graham came up with ways to significantly improve the 1.5’s performance, including the replacement of its brass side weights with heavier ones of tungsten, an improved bearing with a more massive cap, various changes in internal wiring, a far more rigid and better-grounded mounting platform, and a new, sophisticated ceramic armwand. (The original wand had hardly been an afterthought: its heat-bonded, constrained-layer-damped design consisted of an inner tube of magnesium-aluminum alloy and an outer tube of stainless steel.) The arm’s name changed from the 1.5 to the 1.5t (tungsten), then the 1.5t/c (ceramic), and on to the 2.0, 2.1, and 2.2. Each upgrade changed the arm’s sonic performance for the better, mostly in terms of low-frequency weight, solidity, and extension. Even critics of the 1.5’s sound gave it top marks for parts and build quality, which is hardly surprising—Bob Graham is a big admirer of SME and its founder, Alastair Robertson-Aikman. (For an outstanding overview of the original Graham 1.5, see Dick Olsher’s review in the August 1991 Stereophile, Vol.14 No.8; available online at www.stereophile.com/analogsourcereviews/400/.)

The original arm’s detractors complained mostly of its lack of deep bass. Bob Graham responded that he’d paid particular attention to reducing the amplitude of the arm/cartridge combination’s inevitable low-frequency resonant peak by carefully tuning and decoupling the counterweight, and that some listeners were mistaking the result for an absence of deep bass. Graham also rightfully pointed out the difference between the 1.5’s nimble, detailed, well-textured bass and the bloated bottom end of some of the competition’s arms. Still, his later upgrades of the 1.5 focused on and improved the arm’s bottom-end performance. Clearly, the detractors had been on to something: the original 1.5 was somewhat meek in the bottom end. The 2.2 retained the 1.5’s attractive bass qualities while dramatically improving the original’s weight and extension.

The original 1.5 offered impressive overall performance and was particularly adept at resolving inner detail. I’ll never forget the first album I played after installing the 1.5: Joni Mitchell’s Court and Spark. The arm revealed, for the first time in my listening experience, the dimensions of the isolation booth in which Mitchell had recorded her lead vocals. This was not a musically important detail, but it indicated the arm’s exceptional powers of resolution.

Every tonearm design, be it traditional gimbaled bearing, unipivot, duo-pivot, constrained unipivot, or the so-called linear tracker (tangential tracker is more accurately descriptive, considering the design’s goal), has inherent advantages and limitations. The designer’s job, once he or she has chosen the means by which the stylus will be moved across and through the record grooves, is to maximize the strengths and minimize the weaknesses of that choice.

When Bob Graham finished v. 2.2 and realized that his original design could be taken no further, he set about designing what he thought would be an even better arm. After two years of work, the Phantom B-44 has arrived ($4350). Like the original 1.5, the Phantom’s parts quality and fit’n’finish rival those of any tonearm made anywhere in the world, and surpass most.

You have to examine the Phantom yourself to appreciate the differences between it and the original. There are conceptual and mechanical similarities between them, but while the Phantom superficially resembles the original 1.5, it is an entirely new tonearm. Graham carefully thought through his original design and concluded that its basic concepts were still sound—the new arm differs from the old mostly in Graham’s execution of those concepts, and in terms of sheer scale. Graham redesigned the arm literally from the inside out, beginning with the pivot and working outward, part by part. Overall, the Phantom is bigger and more massive. The only part remaining from the 1.5 is the butt end: the DIN jack block.

Like the 1.5, the Phantom uses an inverted bearing fixed to a threaded top cap that screws into the cup assembly, which also makes a convenient well for the damping fluid. The bearing itself is a small-radius (>0.005") tungsten-carbide tip riding in a 0.01"-radius sapphire cup. The Phantom has a threaded post for adjusting the vertical tracking angle (VTA) that’s similar to the 1.5’s, but bigger, beefier, and smoother.

The Phantom also has a removable, Lorzig-ceramic armwand similar to the 1.5’s, but far more rigid, precise, and easier to replace. The armwand has a wider diameter and is progressionally extruded to suppress standing waves, and the tube features a glossy, proprietary overlay of glass that damps vibrations and looks better than the 1.5’s tube. The new connection mechanism is far more robust and secure, with a protruding post of stainless steel that fits deeply into the wand before being screwed in and held under tension at two points. The clearance between post and wand is said to be about 0.001"; lateral play is nil.

The electrical contact pins are of high-copper-content phosphor bronze, to both maintain tension and avoid deformation. The wand’s internal wiring has been improved from the 2.2’s, and is now precision-twisted by machine and layered to isolate the channels from each other, before being encased in a silicone jacket. The entire package is then inserted as a unit into the wand, with the result of another level of damping.

Gone are the outriggers that helped stabilize the 1.5 during play and kept the arm’s center of gravity below the pivot point to create a stable balance system, much as in a laboratory balance scale. This good design is typical of most arms, but it creates a condition wherein the arm, when deflected, tries to return to a resting position (as when trying to track a warped record) instead of following the warp. As a result, the cantilever is deflected, as tracking-force consistency cannot be maintained and the cartridge generator system’s linearity is compromised.

The reason you are advised to measure vertical tracking force (VTF) at the record surface and not above it is because most tonearms are stable-balanced. The higher above the record surface you lift the arm, the more force it will exert trying to get back down to its rest position. The farther above the record surface you measure VTF, the greater it will be compared to what you’ll measure at the record surface, which is where you want it to be accurate. If you have an accurate VTF gauge, measure your arm’s VTF as close to the platter surface as possible, and then again with the gauge sitting on a thick magazine to lift it above the platter. The reading will be significantly higher the farther you raise the gauge, as Bob Graham demonstrated to me with his 2.2.

The Phantom’s tracking force remained constant at all heights. That’s because the arm is neutrally balanced—the system’s center of gravity is at the pivot point, not above or below it. The arm wants to remain wherever it is in the vertical dimension, rather than try to fight its way back to a specific rest position. Graham says that the amount of mass used in the design, and especially the distribution of that mass, contribute to the arm’s stability while playing an LP.

Unfortunately, neutral balance works both vertically and laterally, meaning that the arm would list one way or the other and then remain there, depending on its lateral weight distribution—not good. Graham’s new Magneglide system solves the problem while providing an easy means of adjusting both azimuth angle and antiskating force.

The Magneglide system consists of an ABEC-7 grade horizontal bearing assembly—the same as SME uses for the main bearing of its V arm—of very low mass. The bearing’s actual mass is 10gm, but because it’s directly at the bearing, its effective mass is much less. This assembly never “sees” the unipivot bearing—its only contact with the main bearing assembly is magnetic, via opposite-pole neodymium magnets: one on the assembly, one on the unipivot bearing housing, and both precisely located horizontally from the pivot point.

The magnets’ magnetic forces act to laterally stabilize the arm at the pivot point and give it the feel of a traditional gimbaled arm. Even while playing a record, the arm will not roll. An adjustment screw lets you change the angle at which the two magnets meet, and thus sets azimuth by changing the angle of magnetic attraction; an assembly of rod, weight, and thread attached to the bearing assembly adjusts the antiskating force by physically deflecting the assembly from the position in which it would normally rest based on magnetic attraction alone. There is no physical contact between antiskating mechanism and bearing. Plus, the Magneglide bearing never makes contact or interferes with the unipivot bearing. As the arm traverses the record surface, both the main magnet and the one mounted on the Magneglide move, tracking it without contact and thus, hopefully, without lag.

The Phantom’s counterweight extends from a threaded rod placed well below the pivot point, and, like the 2.2’s, is said to be elastomer-decoupled at a meaningful low frequency, though it feels quite stiff to the touch.

With the exception of the Magneglide azimuth adjustment, the Phantom sets up like the 2.2 in terms of VTA, VTF, antiskating, and geometry, which means setup is both convenient and repeatable—important features for a tonearm that lets you easily switch armtubes. If you want more details about Graham’s ingenious remote gauge for adjusting overhang and zenith, see Dick Olsher’s original review of the 1.5.

My biggest concern was the effect the Magneglide assembly might have on the Phantom’s lateral tracking and responsiveness. Given the benefits of neutral balance and what seemed to be the pivot’s true vertical stability, I figured that any tradeoff would probably be worth it.

The Sound of the Phantom

Because the Phantom is designed to be a drop-in replacement for the 1.5 and its successors, I was able to spend an hour listening to the combo of 2.2 and Lyra Titan cartridge and then, 15 minutes later, listen again, this time with the Titan in the Phantom’s headshell. The biggest difference—which I heard easily, unmistakably, and immediately—was in the bottom octaves, where the Phantom delivered lightning strikes of deep, fast, ultratight bass. Massive attacks dissipated as quickly as they’d struck, leaving no residue.

I was moved to dig out Reference Recordings’ famous Däfos (45rpm LP, RR-12), originally issued in 1983—I wasn’t even in this business back then. A new generation of analog fans deserve to hear this collaboration by Brazilian percussionist Airto Moreira and Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart—especially The Beast, an enormous drum that Hart toys with, bangs, and, during “The Gates of Däfos,” even sends crashing to the floor.

The Phantom’s performance was dazzling on this audiophile warhorse and on all of the other discs I played, guiding the Lyra Titan to new performance heights—and not just at the very bottom. The Phantom is to the Graham 2.2 what Arnold Schwarzenegger is to Wally Cox (youngsters: do a Google search). That analogy may be over the top, but those who felt the original Graham was somewhat meek and reticent will have no such reservations about the Phantom.

The Phantom’s bottom octaves had full weight, as well as the articulation and speed of the 2.2—but more than that, the Phantom delivered a harmonic vividness and sense of musical envelopment that even the 2.2 doesn’t quite get. There was a greater expression of bloom and air, with no loss of detail or control. Every performance parameter seemed expressed with greater confidence and authority, including image solidity and stability.

The 2.2 was always an arm I could respect and—more important to a reviewer—rely on, but I never fell in love with it. That emotion seemed reserved for the Immedia RPM-2 tonearm, which is one reason I had both the 2.2 and the Immedia installed on a Yorke dual armboard. The Immedia has a lusher, richer balance than any of the earlier Grahams, as well as a more open, pristine, and liquid top end and a greater sense of musical flow. But the Phantom easily overtook the Immedia’s superb overall performance, with greater stability, weight, transient articulation, speed, and, especially, a see-into-it transparency that is one of the Immedia’s most attractive qualities. (Immedia’s Allen Perkins told me at the 2005 Consumer Electronics Show that he’s working on his own brand-new tonearm.)

The 2.2 could sound a bit on the mechanical and medicinal side of neutral and analytical; the Phantom is more like an exuberant figure skater who not only gets all the technical moves right, but also manages to exude an emotional intensity that borders on reckless abandon. The Phantom generates musical excitement even as it scores points on the compulsories.

Any worries I may have had about the Phantom’s tracking abilities were quickly erased. The arm admirably acquitted itself on difficult musical passages and test tracks alike. It allowed the Lyra Titan to track the next-to-last, highly modulated antiskating track on the Hi-Fi News Analogue Test LP without any buzzing; more important, the combination’s technical performance on musical torture tracks was flawless, particularly on difficult-to-track inner-groove orchestral crescendos and female vocal sibilants. So smooth and effortless was the Phantom’s sibilant performance that I was reminded of Shure’s 1973 Audio Obstacle Course: Era III LP (TTR-110), which includes Sergio Mendes and Brasil ’66’s “Mais Que Nada,” recorded at increasingly higher levels. I hadn’t played that cut in a long time, but I remembered never being able to track its sibilants properly at the higher levels. The Phantom and Titan sailed through it without smear.

Watching the Phantom confidently navigate a badly warped copy of Clannad’s Crann Ull (Tara 3007) convinced me that Bob Graham’s claims of the Phantom’s neutral balance are justified. The Phantom tracked as if guided by lasers.

The Graham Phantom is a tonearm whose pure, effortless sound I can respect and love. Because it’s a true unipivot but, unlike most such designs—which rely on a second pivot point or a constraining system with added contact points—it doesn’t flop over, it feels good in the hand while retaining all of the benefits of a preloaded, single-point-bearing unipivot design. It’s also easy to set up.p> Because the heights of turntable platters, armboards, and playing surfaces are not standardized, some turntables and cartridges may require the addition of a spacer between the cartridge and the Phantom’s headshell in order to get the optimal range of VTA adjustment. Graham provides a spacer made of Richlite, a composite of phenolic resin and wood fiber that incorporates some of the blue damping material also used in Graham headshells. Bob Graham says the spacer offers such outstanding damping properties that he recommends trying it even if you don’t need it. The Lyra Titan didn’t need it, and once I had it dialed in I wasn’t about to start over, but I did try Graham’s Nightingale cartridge with and without the spacer and can’t say I heard any difference.

The Graham 2.2 remains an outstanding tonearm, so moving on to the Phantom wasn’t the revelation that first hearing the 1.5 had been all those years ago. But the new Phantom is now the pivoted arm to beat, based on my listening experience and its physical and sonic performance and ease of use.

There are some other tonearm contenders that I have yet to hear, such as the Swiss DaVinci Audio Labs Grandezza and the Basis Vector, Basis designer A.J. Conti won’t send me a sample of the latter because he doesn’t believe in cantilevered armboards—never mind that every arm I’ve reviewed has been on one, and no one has complained about the results I’ve heard. I also wouldn’t mind giving a listen to one of the Schröder arms, but Frank Schröder apparently can’t keep up with demand—a review is the last thing he needs. Whatever those arms’ sonic merits—they’re said to be considerable—the Phantom’s switchable armwands makes it an ideal choice for stereo/monophiles.

The Phantom, with all accessories, including Graham’s unique alignment jig, will set you back $4350. Is it worth upgrading from the 2.2 or one of the older Graham arms? I was expecting a modest improvement when I dropped the Phantom into my system, but the differences were not subtle. (This will be especially true if, like me, you have a full-range system that goes down to 20Hz or below.) Only after the immediately obvious improvements had settled in did the subtler ones—those having to do with musical flow and a sense of certainty, those that kept me listening long into the night, night after night—begin to assert themselves.

Sidebar: In Heavy Rotation

1) Kathleen Edwards, Back to Me, Rounder LP

2) The White Stripes, Get Behind Me Satan, V2 CD

3) Spoon, Gimme Fiction, Merge 180gm LP

4) The Mars Volta, Frances the Mute, Gold Standard Laboratories 150gm LPs (3)

5) Lightnin’ Hopkins, Lightnin’ in New York, Candid-Navarre/Pure Pleasure 180gm LP

6) COB, Moyshe McStiff and the Tartan Lancers of the Sacred Heart, Radioactive 180gm LP

7) Abbey Lincoln, Straight Ahead, Candid-Navarre/Pure Pleasure 180gm LP

8) Lou Donaldson, Lou Takes Off, Blue Note/Classic 200gm Quiex SV-P LPs (stereo & mono)

9) John Lennon, Mind Games, Capitol/Mobile Fidelity 180gm LP

10) Sonny Boy Williamson, The Real Folk Blues, Chess/Speakers Corner 180gm LP

- Log in or register to post comments

i think michael has some kind of DCS CD player, but he'll have to confirm exactly which one. as far as "get behind me satan" on CD, it's because the original vinyl was only 600 promo copies. jack wanted to do a separate recording of the album for vinyl but it didn't happen. therefore, only CD existed until the 2015-16 third man 2LP pressings. original promo LPs are rare... and to think that there are rarer third man releases...

This is one of the old Analog Corners that are being posted here so we can enjoy them again. It's from 2005.

it's so easy to get enveloped in the story that a certain timelessness evolves, similar to what I get with Malachi's reviews given his (lack of) age.

I'm surprised the tires didn't pop on that minivan. I nearly crashed a small Japanese pickup hauling a 78 collection. There was more weight over the drive axle and the front tires almost came off the ground. Would've been a spectacular accident too.

A file with a series of stored documents, Block Blast use and set up a security mechanism.