Building Gold Star Studios, Phil Spector and Alvin & The Chipmunks Come to Play

ROSS: We bought the parts. There were no recording consoles available. We had a broadcast console that was available to us. It was a stereo console because one channel was for cuing and the right was for the air. It was gorgeous. A guy had this wonderful board with the colored knobs and [it was] just what we wanted. And so we got it for a good price and I said, ah, we got the console.

FREMER: So you had to make an investment. So you had to have savings? You borrowed?

ROSS: We borrowed the difference, whatever. Hey, I wasn’t a GI so I had a problem. Anyway, we found out that this console was hot. [LAUGHTER]

FREMER: And not because of the tubes.

ROSS: No, it wasn’t because of the tubes. It was hot, it was just – it was never really his to sell. At least that's what he told us, unless he got more money for it, and then Dave had to go back and redesign and go build a board. And that board actually, I have a picture of it, it was a beautiful board. But Dave had to then go back and build us a console from scratch, which is the one Phil poses in front of. We built a beautiful board. But it’s unfortunate, that set us back emotionally about three, four months. And we took over, so we opened up our own studio. We found a place on Santa Monica Blvd. that was owned by a dentist and that had a store and he owned a building, and he was going to retire and he wanted to know if we wanted the store. I say, well, we could use it, we’ve just got to move the walls around a little bit. So I copied Electro-vox to a tee. I had the studio in the same place. I figured I’ll be using the same customers; I’d confuse them. They won’t know where they are. I even called the songwriters up and said, hey, I’ve changed my location, come over here. [LAUGHTER] So I knew all the songwriters. When they walked in they’d say where’s the girl that used to be here? [LAUGHTER] I said, yeah, well, she’s not here any more. We got another girl. And it was wonderful. They came to Gold Star thinking it was Electro-vox and it took them a while to realize – what are you doing? I worked with all the songwriters at that time, the Tobias Brothers, and Livingston and Evans, and Jimmy McHugh. I mean you name them, ASCAP –

FREMER: And they were coming to do demos?

ROSS: Yes, of the songs. Yeah, they got – we worked with demo singers and I had musical arrangers, Danny Gould and Don Ralke. These are all people that did the demos, and Bob Grabeau, they all sang these songs, and Robie Lester, they sang these songs and they performed these demos so beautifully that the record company would say if this record comes out we’re not going to do it with our artist. Now we did a song called “Cry” that Johnny Ray got a hold of, and Lou Dinning did it, of the Dinning sisters, and she sounded like Johnny Ray with the echo on it, and they said if that record comes out we’re not going to do it. So she copied the arrangement, Don Robertson did the arrangements for his wife, Lou, and the demo came out and Capitol heard this thing and said if you put this out we’re not going to do the record, so that was a demo. There were such glorified demos coming out of Gold Star that the feeling was if those demos – who knows what a demo is, you know. A demo’s a record. Nowadays I hear demos all the time and they could be called records. If people don’t know, if it’s good, it should be a record.

FREMER: That’s right.

ROSS: So we had fun. We made those wonderful demos. We called them glorified demos.

FREMER: You made them as good as you could make them, sonically.

ROSS: I’ve got to tell you, a lot of the records I’ve done and the sounds that we’re famous for, the creativity, like on “The Birds and the Bees,” I put the guitar through the Leslie to get that sound. And they’d say, wow, what made you do this? I was tired of hearing a regular electric sound and I wanted to see what it would sound like having a spinning song, an organ, a Leslie sound.

FREMER: Great idea.

ROSS: Okay, we did it, we sold a record. When we made “The Big Hurt,” we put two tapes together to get the phasing in it. I cut the session originally, but Larry Levine phased the tapes.

FREMER: Is it the first time that was time?

ROSS: The first time it was ever used in a record that made it to the air.

FREMER: That was Timi Yuro?

ROSS: No, her name was Miss Toni Fisher.

FREMER: Oh, I’m thinking of a different song. Oh, that’s right.

ROSS: And it was the first time people ever heard putting the two tapes together to get that phasing.

FREMER: So you had two machines --

ROSS: Two locked-in monos.

FREMER: Ampex?

ROSS: Yeah, locked-in Ampexes. We locked up to a third Ampex. Now I could have gone back – when we did it he wanted the voice on the front more. I said – Wayne Shanklin was the producer. I said, Wayne, I could take – it’s two track, binaural, the voice is on one track, the band’s on the other, I can change the balance. He said, no, I like the sound that it’s got. I just want the voice in front more. I said, well, I don’t want to get into details. He didn’t know what I was talking about. So we took two monos and the next thing you know we’re getting this thing locked in and just passing each other and getting this phase effect.

FREMER: It makes it sound bigger.

ROSS: Well, it wasn’t that, it’s just it’s so unusual it’s like – most people would say don’t do that, let’s go from scratch [and then you can forget that], but he used the effect to his advantage. We couldn’t predict when it would happen, we just used enough of it to start it and stop it at the right time. And then we edited the tape together.

FREMER: Now all these songs were going to be used on AM radio for the most part.

ROSS: Yes.

FREMER: Did you take that into consideration when you made these or did you just make them sound as good as they could sound?

ROSS: No, you made it sound good on AM radio. As far as we were concerned FM didn’t count.

FREMER: No, of course not, in those days.

ROSS: AM, that’s right.

FREMER: And so what monitor and speakers did you use? Did you use A-7s?

ROSS: No, not the A-7s, the Altec 604s. The A-7s were not good enough. They were good in the studio but I didn’t like them and musicians didn’t like them either. Cinerama it was good for but it was not good for recording. We bought two A-7s and we stuck with them. But the 604E s and the 604Ds were the best Altecs you could have and that was the one that gave me my solid sound. When it was good on that it was good on the air. And then what I would do, I would take a copy of the record and play it on a one-tube oscillator and sit in the car and dial in 600AM on the dial and he would broadcast it outside.

FREMER: Smart.

ROSS: Listen to it on the radio. I said come here, here’s what your record is going to sound like when it’s on the air.

FREMER: So you didn’t have to give the payola to hear it on the radio for the first time, you could hear it before the payola.

ROSS: There was a disc jockey named Don Steel who was a very dear friend of mine. He started [to play] Sonny and Cher. He got the first release on KHJ Boss radio. So the thing is this, when we made Sonny and Cher’s record I took the tape, played it on the thing and listen to it on my car speaker and I’d say here’s what’s on this side, so I add a little more bottom, little more top, then I make the master and get it a demo over to Don Steel and he had it on the air. The next day at three o'clock we went on the air. So everything was equalized. I knew exactly what it was it going to sound like.

FREMER: “I Got You Babe,” was that recorded at your studio?

ROSS: Oh, yeah.

FREMER: I’ll tell you, there’s a copy of that going around, you know, on a CD. Do you know about that copy? There’s a copy going around of that un-mastered, un-compressed, just obviously the raw tape that is so unbelievable. I play that for people and they just flip out.

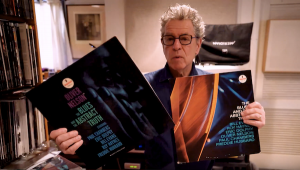

ROSS: There’s my picture (Ross pulls out a Sonny & Cher album).

FREMER: Well, I’m telling you, I wish I had that thing on me. You’d go hear it in a good room and that is the most amaze – did you record that?

ROSS: Yes.

FREMER: That is the most amazing sound. I play it for other people and they say why would he take such care to make something sound so good in stereo when it’s going to sound like crap in the – it’s like the best recorded oboe, you know that oboe that’s --

ROSS: Yeah, George Poole (the oboe player)

FREMER: The bottom end on that record, there’s so much bass on that, but good.

ROSS: Well, we’ve got the tapes on these things. Those tapes were basically a mono-track. It was recorded the way Phil Spector recorded. By the way, these are the invisible men (referring to people listed on the back of the first album). These are the original managers (Stan’s referring to Charlie Greene and Brian Stone). You’ll never see their names appear again even though they brought Sonny and Cher, Iron Butterfly, Buffalo Springfield, Black Oak Arkansas and others to Atlantic. Sonny was a “gopher” who had a girlfriend and they wanted to be recording stars so we did a record for them under the name of Caesar and Cleo but it died. But when it became Sonny and Cher it became personal!

FREMER: Right. Yeah, you told me that.

ROSS: You’ll never see them appear again.

FREMER: Look, it’s “Stan Ross our sound engineer” (written on the Sonny and Cher album jacket). Yeah, well, let me tell you something, I wish I had that CD on me so I could play it for you in one of these rooms because it is astonishing. People go crazy. And the volume drops down towards the end. You know what happens, it goes to the false ending and then it comes back up again.

ROSS: The instrumental goes back up.

FREMER: Yeah, and it gets so loud, and I know that – I’m sure that when the record came out it’s compressed on the record, it couldn’t possibly have done that but… it’s awesome.

ROSS: I hear stuff with Phil Spector stuff in stereo and it wasn’t done in stereo, the Christmas Album. We did the Phil Spector Christmas Album, we mastered it the Christmas Album mono. Phil dug mono.

FREMER: I know, “back to mono.”

ROSS: He never did stereo. All of a sudden I’m getting a pressing from England and I’m listening to the record and it’s in stereo.

FREMER: So they must have gotten the – was it a multi-track?

ROSS: No, but the multi-track is mono. You see what Phil did is – this is the big secret of what “the wall of sound” is, Larry Levine, who engineered all of Phil’s stuff at Gold Star, did mono on everything and ran multi-track, but recorded mono – what you heard is what was on the tape, mono. Phil always wanted to hear things together, not spread out. So even though the guitars were one track, the bass on another track, the drums on a track, whatever, the piano – whatever – whatever was separated was fine except he wanted everything mono because that’s how he wanted to hear it.

FREMER: Right, so you monitored it…

ROSS: So we took that and we kept the mono and we transferred that to one of the multi-tracks and added to that more echo.

FREMER: So someone got a hold of those tape elements.

ROSS: But they were all separate.

FREMER: Well, what do you think they did then?

ROSS: Well, I have a funny feeling that what they did, they overlaid new strings on top of the old ones.

FREMER: I wonder.

ROSS: They had to because there’s no other way they could have made that happen. The Christmas Album –

FREMER: Did they use comb filters on some of those things to --

ROSS: No, this is not – we’ve done that too with the gadget.

FREMER: -- which ruins records. Instead of one good mono-track you have two crappy stereo tracks.

ROSS: Yeah, it didn’t happen that way. This actually unfortunately, the stereo, the strings are really pure. I mean you can listen to one speaker and see how the strings come through with the rhythm in the other track.

FREMER: So that’s what they – yeah. So, did you know that you were recording real hi-fi? Did you have a good hi-fi at home? Were you a hi-fi nut?

ROSS: I never played anything at home except things that I did, I kind of enjoyed.

FREMER: Did you have a nice sound system? Did you have a McIntosh?

ROSS: No, it was a 78 mono. It was simple. We played – I had a good system but it was fair. When I got home I wasn’t ready to play – I wanted to play AM style.

FREMER: Right, right.

ROSS: So, in other words, a record I did, we did a record years ago called “The Trouble With Harry,” Ross Bagdasarian with the Chipmunks. And Ross was a buddy of mine. We started the Chipmunk thing. Actually Dave Gold came in on weekends to experiment with Ross on getting the double-speed sound working. You know, that whole thing that’s named after everybody in the family.

FREMER: That’s named after everybody in the family?

ROSS: In the family. In other words, Alvin is Al Bennett of Liberty Records, Theodore was Ted Keep, the engineer over at Liberty, Simon was Si Waronker, and David Seville, David was Dave Gold, my partner, and Seville was…. FREMER: …his car…

ROSS: … his wife’s maiden name.

FREMER: That’s great to know. [LAUGHTER] That’s hilarious. And was that done at your studio, too? ROSS: Most of it was done in our studio but we did a thing called “Arman’s Theme,” which is an instrumental thing that he loved, we did that, and it had that double speed piano before we did the Chipmunks.

- Log in or register to post comments