This is a fun interview with a very sharp guy. He's right about the 100-watt Marshall amps (usually two of them), but I would point out to Stewart that Andy Summers always played a Telecaster, not a Strat. If I was a nitpicker, that is.

Drummer Stewart Copeland Explains How He Maximizes the Dynamic Range on His New Police Deranged for Orchestra LP, and Why Its Most Primal Elements Sound Best on Vinyl

Stewart Copeland has always followed the beat of his own drum — or, rather, he’s always been the consummate rhythmatist who’s unwaveringly laid down his own style of drumming perpetually in service of the song at hand. Whether he’s been behind the kit for the underrated early-’70s progressive-leaning collective Curved Air, the groundbreaking megaplatinum neo-rock trio The Police, his brief solo guise under the nom de artiste Klark Kent (a semi-lost cult favorite album recently reissued on LP during RSD 2023), or his litany of soundtrack and orchestral work alike, Copeland’s performances behind the kit are both instantly identifiable and inherently inimitable.

And now, the sonic fruit of his latest twisted muse, if you will, has manifested itself in a solo project somewhat cheekily dubbed Police Deranged for Orchestra, consisting of ten classic and deep-cut Police tracks rearranged — or “deranged,” in Copeland’s titular parlance — as released in its 1LP form by Shelter/BMG this Friday, June 23.

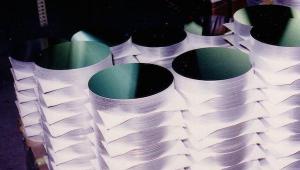

While I’m still awaiting confirmation on the pressing plant locale and lacquer-cutting details for the Deranged vinyl (I will add them here accordingly once I have them in hand), there’s no doubt this LP (SRP: $26.99) is the best way to hear the truly broad scope of such detail-oriented reimagined Police songs both well-known (“Don’t Stand So Close to Me,” the ever-ubiquitous “Every Breath You Take”) and semi-known (“Tea in the Sahara,” “Murder by Numbers”) alike, with a guitarist, bassist, and three separate vocalists accompanying the noted percussionist/drummer along with the orchestra at hand. Copeland also arranged, orchestrated, and co-produced Deranged, which was conducted and co-produced by Edwin Outwater and produced and mixed by Craig Stuart Garfinkle.

The origin of Deranged technically began when Copeland helmed Everyone Stares: The Police Inside Out, a band documentary released in 2019 for which he reconstructed a number of Police classics by accessing outtakes and session leftovers to give many of their classic songs some truly fresh reads.

“Yeah, these are the same ‘Derangements’ I strung together for the movie,” Copeland confirms of the new album, “only they’re done by orchestra. The mission to score the Everyone Stares movie was to have alternatives, as in — ‘It’s gotta be Police, but it’s gotta be Police you haven’t heard before.’ So, I found all those strange bass lines and those strange, obscure guitar lines and vocal lines, and strung them together into versions that were all ‘Deranged’ to score the movie.”

Continues Copeland, “And now, I’m out playing shows with those same Derangements — but they’re all orchestrated for orchestra, and it seems to be working pretty well. They burn down the house every night. It’s a really easy, successful show — and a lot of fun. Yeah, I love playing those songs.” One could even go as far to say that every little derangement on the accompanying new album is, well, magic.

During a recent Zoom interview, Copeland, 70, and I discussed how he opened up the dynamic range with all the Derangements he came up with for this album, how he shepherded the “perfect” snare, and just how meticulous he got when he wrote out the entire Deranged score for each orchestra member to follow. There really isn’t any need for bloodshed / You just do it with a little more finesse. . .

Mike Mettler: Obviously, we have your own drum templates for all the Police songs that were recorded 40-plus years ago. Give me one good example from the Deranged record where you changed how you played that specific song to fit the new orchestral arrangement.

Stewart Copeland: Well, I can give you one — one specific example — and that would be (slight pause), all of it. (MM laughs) And the reason is because my instrument is designed to compete with giant amplification, a sound killer that’s designed to be very loud.

For the music I orchestrated for this album, those violins are about a foot long and made out of wood, and they’re not as loud as a Stratocaster through a 100-watt Marshall stack. Even though there are a lot of those violins here, I still have to take my volume way down. For the normal rock gig, the dynamic range is from like 8 to 12. When you see an orchestra at a concert, it has huge, dramatic impact. It feels very big and very sonorous, and very deep and very high — but. in fact, it’s an illusion, because it’s a quarter of the volume. If you’re in that same hall watching a rock band, you wouldn’t notice it unless they came one after the other, but the difference in volume is quite dramatic. The orchestra feels bigger because it’s a more sonorous sound.

With my drums, if I hit one cymbal crash, I lose the next two bars of that little violin. But I can now play so quietly that I can hear that violin player who’s 20 feet away from me. And the reason is — well, I mean, if I didn’t write the music myself, I’d be like, “Screw it! My name is on the ticket, and I’m gonna play some drums! I’m gonna bang some sh--!” But since I’m the one who put those notes there on that score, I want to hear them — and that imposes discipline on me.

Now, interestingly, I actually can play in a more exciting way because of that dynamic range, and my dynamic range is now from 0 to 12. Mostly, I’m down at the 4 range, but at that level, I can use all kinds of technique — the persnickety sh-- you wouldn’t hear in a rock environment because it’s just too loud. You can’t hear that. All you can hear is the big stuff. But now I can actually do more interesting stuff. My vocabulary is wider.

Secondly, the drums sound better when being caressed, rather than killed. You know, they respond with love when you don’t hit them with homicidal frenzy! Also — nobody gets a headache. (MM laughs)

Mettler: I can dig that. So, “Demolition Man” is a very aggressive track that I believe is Track 5 at the end of Side 1 of the original album it’s on, Ghost in the Machine [released in October 1981]. And now it’s Track 5 here at the end of Deranged Side 1, which is something I’m guessing was a specific sequencing thought from you for the vinyl presentation. Did you feel “Demolition Man” absolutely needed to be at the end of Side 1 on the Deranged vinyl release?

Copeland: Yes, I had that in mind. For the CD release, the songs just flow all the way through, but I had to bear in mind to have the right break in the middle for the vinyl.

Mettler: That makes sense, because hearing “Demolition Man” in the middle of a side would have sounded quite odd to me. I’m glad you have it right where it is here, whether you did it consciously or subconsciously.

Copeland: It probably was subconscious! (both laugh) I doubt if I’d have the faintest idea of what the writing order of any of the Police albums might have been from all that time ago — but I’m glad there are people who do know this stuff, and I’m humbled by the interest people take in such minutiae.

Mettler: Well, yeah, that’s exactly what we do here, so thank you for noticing. (more laughter) Did you get a test pressing of the Deranged LP to do your own QC with personally?

Copeland: Yes, I did. But my sign-off on it was not as valid as that of my proxy, Craig Stuart Garfinkle — who also was the recordist — and he did give me a few notes. You and he would get along great (MM laughs), because he was all over exactly all that stuff you’re asking.

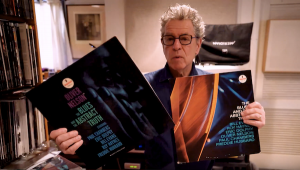

And he was all over the mastering too, to get everything right for not only the vinyl, but for the CD as well. He was so into it that I felt like I could relax a little, because I’m the one who listens to the music, not the sound of the music. I listen to the tune, and to the rhythm — you know, the primal elements.

Mettler: I get it. It must be nice to have someone like Craig whom you can have a level of inherent trust with like that.

Copeland: You’re right. I’m the guy who’s gonna go, “Turn it down? Are you insane? Why would I want to do that? More drums!” (laughs)

Mettler: Well, considering you’re the guy who has a snare that’s literally called The Snare, I can’t argue too much with you about that.

Copeland: And it’s on this record, by the way. That’s it, right there [Copeland walks over to his kit and points out his infamous snare, as seen above], and it’s all over the record.

I broke a lug on it, so it had to go the workshop. The cool thing is, I have more of them now. I sent it over to Japan, where the Tama folks analyzed the metallurgy, the exact circumference of the rims, and all the elements. They sent maybe three or four prototypes back and forth until they finally landed it — and now I’ve got the perfect snare. I’ve got 20 of them, and it’s in stores across the land. It’s actually a hit snare. Most studios nowadays, they’ll have a Ludwig Black Beauty in a closet somewhere — and the Stewart Copeland Snare.

Mettler: Wow. So what would you consider to be the best snare moment in your catalog? What’s your favorite snare moment, or moments?

Copeland: Oh, let’s see here. Probably a track like “One World (Not Three)” [Track 3 on Side 2 of the aforementioned Ghost in the Machine]. But, God, it’s hard to pick one out there. I mean, I just work here — your job is to pick it out, and find it! (both laugh)

Mettler: Well, that one’s not a bad call. I’m also partial to your hi-hat work on Peter Gabriel’s “Red Rain” on his So album [released in May 1986], as we’ve discussed before.

Copeland: I remember. I didn’t have any idea what the track was going to be because Peter hadn’t written the song yet. We were just creating grooves — of which eventually he would carve up and turn into a record.

And then, a year later or something, imagine my surprise — his record comes out and goes platinum, and he sends me a couple of platinum albums. I had to check the liner notes to see what tracks I played on, because I never heard anything about no “Red Rain,” or anything else. I just heard a bass line. (chuckles)

Mettler: Well, you must have done something right on that record to get him to send you those platinum albums. (both laugh) What was the process behind the Deranged recording? Was everybody in the same room with the orchestra, or no?

Copeland: No! No, I recorded the orchestra in Dublin. The singers were each in their own studio, and I recorded my drums right here in my studio [points at the massive drum setup behind him], and so on — which was not optimal, and not totally efficient — but I was able to get more bang for my budget buck by doing it this way. I was able to get more stuff by cutting it all that way, rather than booking one big studio for the duration.

Mettler: Knowing how you tend to work, I imagine you wrote the scores out yourself for everyone to work from, yes?

Copeland: Oh yeah, I scored the whole thing. Orchestrated it. Every dot on the page. Every tenuto, every accent, every articulation, was me agonizing over it — which is very different from making music to come out of speakers, when you’re making a record. That’s where you sit in the studio, and you fiddle the faders until it sounds (exclaims), great!

When you’re creating a score, you’re creating a piece of paper — and you can’t hear it. You’re looking at dots on a page; you’re not hearing it. Well, you can hear a facsimile of it, a synthesizer version of it, but you have to imagine what it’s going to sound like when you get to the Atlanta Symphony and you’re sitting there with 50 musicians in their chairs looking at those squiggles you put on the page. What’s it gonna sound like? Count ’em in, and find out.

Mettler: Yeah, that’s the only way to know.

Copeland: Yes — and I’ve been doing it for quite some time now, so I’m a little more confident, and I can work a little more quickly. But I do have to scratch my head and ponder a lot more than if I was just mixing a record. You mix a record, and if it sounds great — we’re done. That’s it. But creating a score — putting it all on the page for others to read at some later date — that takes a lot. I gotta be a lot more careful and think harder, and bust my brain a little harder on making sure it’s right.

Mettler: Have any of the musicians said something to you like, “I don’t think this note is right here. Can we change it?” Have you had that kind of interactivity?

Copeland: At first, yes, because there were mistakes. And I got out the pencil, and I revamped the score. Indeed, there were places in the low end where my synthesizer’s version kinda hides the mistake down in the low end. But when I get in front of the orchestra, I can hear that the tuba was clashing with the double bass, so I did have to fix a few things — just tidying up intonation like, “this note should have been flatted, but was natural,” and so on.

Mettler: Do you have a specific Deranged song example for which you had to do that?

Copeland: No, no — these are just tiny, little details here. Just tiny little things. After the first show, I’d get out this pencil, and when we’d get to the next orchestra, it would be, “Oh, by the way — bar 39, that’s a B-flat on the oboe there. Sorry about that.” And then they get out their pencil, and they fix it. Eventually, instead of saying that same thing to every orchestra, I just redid the scores. I put all of the pencil into the ink, so the rehearsals go more quickly that way.

Mettler: We have ten tracks here on Deranged. What was the process of choosing what songs went on the LP?

Copeland: It started out with the Derangements that I used in the movie [Everyone Stares], and then I started to add to them. Finally, the last one was like (says with mock resignation), “Okay. Alright. Okay. Everybody wants to hear ‘Every Breath You Take.’ Okay!” That was the only one that was kind of an afterthought — and it’s the biggest worldwide smash hit on the list. You know, I’m a total artist, searching my soul to reach the muses — but also, you gotta do what you gotta do. [“Every Breath You Take,” a No. 1 hit across the globe, was one of the many hit singles culled from June 1983’s Synchronicity.]

Mettler: Yeah, so when you do Volume 2, we’ll be getting stuff like “Contact” [from October 1979’s Regatta de Blanc] and maybe another Police song or two that you’ve sung yourself, right? (Copeland laughs) Have you thought about doing Derangements for Police songs that you actually sing?

Copeland: Yeah. Well, I did. What actually started this off is — because I’ve been playing concerts with orchestras for decades and I’ve been playing concerto for something that some orchestra had commissioned, or done film music, and whatever — what I did was, I started to drop in really obscure Police tunes like “Miss Gradenko” [from Synchronicity] and “Darkness” [from Ghost in the Machine], and so on. They went over so well that my management said to me, “Ahh, dude — why don’t you throw in the hits?” And I said (mock exclaims), “No, no, no no. . . (slight pause) Yes!!” (MM laughs)

And that’s because I had these Derangements. I had these other versions. It wasn’t me just going out and doing “Roxanne” [from November 1978’s Outlandos d’Amour] again. I’ve got this other version of “Roxanne” that I feel a lot more ownership of, and so I felt better about doing it that way. Once the ball started rolling on that and I started playing these shows, I went, “Okay, that was a good idea.”

Mettler: I also like how you do lesser-known songs here like “Murder by Numbers” and “Tea in the Sahara” [both songs appear on Side 2], which I think are excellent choices to have in this collection.

Copeland: Yeah — some good, obscure choices there.

Mettler: They are good choices, because there are a lot of Police tracks people know and have heard many times like “King of Pain” [Track 4 on Side 1], which admittedly does have a completely different feel here. But hearing a track like “Murder by Numbers” — which, if I remember correctly, was the bonus track on the cassette version of Synchronicity and wasn’t even on any version of the album early on. Just about the only way you could hear it in those days was to buy the cassette before it was on the CD that came out a few years later.

Copeland: That’s right! Well, it was a B-side of a single as well [for “Every Breath You Take”].

Mettler: Why do you feel a song like “Murder by Numbers” just had to be part of this project?

Copeland: Well, when we play it live, it goes down as one of the biggest we play. It’s not one of the hits — it ain’t “Every Breath You Take” — but just when the orchestra plays it, it really lights up. And whether they’re familiar with it or not, it really works on the audience. That song is a big hit onstage, even though it’s one of our most obscure tracks.

Mettler: Will there be a Deranged orchestral sequel of any kind? I mean, ten songs on a record almost seems like there’s not enough of it, at least not to me. Can there be a Volume 2 like I mentioned earlier — and can I vote for you doing “Secret Journey” [from Ghost in the Machine] on it?

Copeland: Ahh, you’ve gotten into the swell of it! Sure, why not? Well, there are a few more hits that I didn’t do. I mean, “Bring on the Night” [from Regatta de Blanc], I still gotta do that. So, yeah, there’s a few more.

Mettler: When you put Volume 2 together, we’ll talk again. But for now, we gotta go, so let me give you my last broad statement to wrap things up. Let’s vault ourselves 50 years into the future, so it’ll be 2073. Unless there’s some weird science going on, you and I are probably physically not on the planet at that point, I’m guessing. But however people listen to music in 2073 and they type in the name “Stewart Copeland” and/or “The Police,” what do you want that listening experience to be for them?

Copeland: Let’s see now. Let’s go with “Message in a Bottle” [from Regatta de Blanc]. And I would immediately want them to start waving their tentacles when they’re listening to it — and then they can all be consuming each other next. (both laugh)

STEWART COPELAND

POLICE DERANGED FOR ORCHESTRA

1LP (Shelter/BMG)

Side 1

1. Don’t Stand So Close To Me

2. Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic

3. Message In A Bottle

4. King Of Pain

5. Demolition Man

Side 2

1. Murder By Numbers

2. Roxanne

3. Tea In The Sahara

4. Can’t Stand Losing You / Regatta De Blanc

5. Every Breath You Take (Intro)

6. Every Breath You Take

- Log in or register to post comments

I never saw Andy play the Strat. Caught them (free tickets due to managing a record store!) in 1979 at Mississippi Nights, a large club, and it was flat-out amazing. 1982 at the Checkerdome arena was less exciting but very, very good. The Synchronicity Tour show in 1983 wasn't nearly as fun. The trio of backup singers were mixed MUCH too loud and there was no spontaneity at all, probably due to synth programming or recorded backing tracks.

but those backup singers were worse. They swayed around wearing weird robes, affected some sort of Arabic accent and almost ruined the experience for me. That Mississippi Nights show was fantastic, though!

With all respect for Mr. Copland and his musical lifework, but in my opinion this album is very disappointing. A drummer‘s album in terms of way too prominent drums, the lead vocal technically fine but way too disappointing in voice sound & character compared to the original, no groove, rhythmically stiff like an army band and a somehow annoying musical realization and sound on top end. It’s seemed like a quite bad and annoying cover band to me.

But good and interesting interview!

I took another look at his book, One Train Later. He says several times that the Tele through an Echoplex pedal became the signature guitar sound of the Police. On page 208 he notes

I looked at his book One Train Later, which I read a couple of years ago. Several times he mentions that the Telecaster run through an Echoplex became the signature guitar sound of the Police. On page 208 he says, "I rarely try any other guitar than the Telecaster because it seems to work on just about everything". That changed due to an accident just before a show in Boston in 1982. He leaned the guitar against something that looked like a boiler prior to the show. Whatever it was, it demagnetized the back pickup of the guitar! He had it replaced, but the Tele never sounded quite the same (page 305). After that he began using the red Stratocaster more, although he later said that people didn't like it when he played the Strat in concert.

After the band broke up, Summers more or less retired the Tele and Echoplex, as that sound was so closely identified with the Police. He has used many guitars since then, notably several Gibsons for his more jazz-oriented work.

He never actually mentions the Strat in the book, which was published prior to the reunion tour.

The headline says, “…and Why Its Most Primal Elements Sound Best on Vinyl”, but I can’t find any such thing in the article?