Climbing "The Wall of Sound" With Gold Star Recording Studios Co-Founder Stan Ross

Back in the 1950’s, with major labels like Capitol, RCA and Columbia owning their own Los Angeles recording complexes, small, independent recording concerns were left to pick up the scraps: voice-overs, song demos, commercial jingles and other small-time bookings.

It was upon that sort of wholesome fare that Gold Star Studios thrived during its early years in the 1950’s. Founded by a couple of adventurous young friends, the studio also began attracting more creative types, drawn both to the sound of co-founder Dave Gold’s custom-designed recording gear and “secret-recipe” reverb chambers and to co-founder Stan Ross’s recording and producing inventiveness. As you’ll read, Ross’s creative instincts helped turn “tunes” into some of our most enduring and memorable pop-musical treasures.

The studio, located at the corner of Santa Monica Boulevard and Vine Street in the heart of Hollywood, was where Phil Spector and recording engineer Larry Levine (who passed away May 8, 2008)) used Dave Gold’s echo chambers to create his famous “Wall Of Sound.”

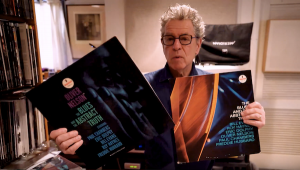

Gold Star was Brian Wilson’s “…second favorite studio…” according to engineer Mark Linett, who co-produced the Pet Sounds box set (Wilson’s favorite was United/Western). Gold Star is where Brian Wilson recorded “Good Vibrations,” “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” and the massive “I Just Wasn’t Made For These Times.” Gold Star is where Sonny Bono learned his craft watching Phil Spector work and where the couple recorded “I Got You Babe.” It’s where Neil Young producer and confidant David Briggs took Neil Young’s master tapes for lacquer cutting. Look on the inner groove area of original pressings and you’ll see the “DG” (Dave Gold) scribe.

Through my friend, publicist Phil Callahan, a friend of the Ross family, I was afforded the opportunity to sit down and talk with Stan Ross on June 4th, 2006 at the conclusion of Primedia’s Home Entertainment Show in Los Angeles. Wind Stan up by placing a microphone in front of him (or not!) and out come the stories. Just when you think he’s told all he knows, out pops another surprising gem from this gruff but endearing character.

During his heyday, the Zelig-like Ross seemed to be everywhere, inserting his creativity into everything from “Tequila” by The Champs, to Alvin and The Chipmunks, to Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth.”

What a time it was in the clubs, on the streets and in the recording studios of Southern California through the 1950’s and ‘60s! Gold Star was in the middle of it and so was Stan Ross. Enjoy this small snippet of that golden era through Ross’s unique perspective.

FREMER: We’re talking to Stan Ross who – you owned the studio?

STAN ROSS: I was a co-owner with Dave Gold.

FREMER: One of the owners of Gold Star Studios, the famous Gold Star Studios, where – tell us some of the artists who recorded there.

ROSS: Well, let me start at the top. Sonny and Cher, the Righteous Brothers, Eddie Cochran, Bobby Darin, Ritchie Valens, Jewel Akins—he sang “The Birds and The Bees.”

FREMER: Was “Oh Donna” recorded there?

ROSS: The vocal of “Oh Donna” was recorded at Gold Star. The backing track was done at Bob Keene’s studio. He owned Del-Fi Records. So was “La Bamba.” “Tequila,” by the Champs was my production.

FREMER: And, of course, they became, uh, Seals and Croft.

ROSS: And eventually [UNCLEAR] out of that, right. So, that’s the beginning. Now then, of course, we all know about Phil Spector and the “Wall of Sound.” Now, he called my echo a “wall of sound.” Well, it was a wall and it was a bunch of sound but it was a necessity.

FREMER: Right. Now, let me ask you this question, how did you get into this biz? How did you get into the recording business?

ROSS: Well, I attended Fairfax High, I graduated in 1946, and I had a musical column called “Musical Downbeat” in the Fairfax Colonial Gazette newspaper and every so often I would have a scoop and I’d call it “Off the Record.”

FREMER: Were you there when Herb Alpert was there or you were –

ROSS: No, I was there before him. Herb was about four or five years after. His brother was with me, Dave Alpert. So I used to write a music column like this in school. So my homeroom teacher says to me, Stan, are you looking for a job after school? I said yes. She says, I tell you what, there’s a studio in Hollywood looking for an engineer. I said what’s that? It’s a recording studio. I said what’s a recording studio? I always thought Capitol had a studio, RCA had a studio, Columbia had a studio, Decca had a studio and that’s a recording studio. What is a private recording studio doing without having a label?

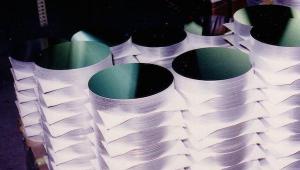

So she says, no, there’s a studio in Hollywood on Melrose Avenue across from Capitol that’s looking for an engineer, and they want someone who’s graduating in June. I say, “well, that’s me.” So I went down there and I went to a place called Electro-vox on Melrose Avenue right across from Capitol, and (the owner) says to me, well, can you work after school, then come in and work full time? I say yes. I say what are you paying, Mr. Gottschalk. This is Bert B. Gottschalk, the man who invented (the glass recording) disk. He invented the Gottschalk process of recording on disk. He used to make his own disks, glass records, during the war. Glass based disks, lacquer coated glass. He was the inventor. I mean one of the pioneers.

Anyway, so he said, well, $28 dollars a week. I said, okay, after school, that’s great. Then when I graduated in June I said, oh, I’m here full time. He says good. I say, now how much am I getting now? He says $28 dollars a week. I said I think we got something wrong here; that’s part-time after school. He says we discussed it and you said $28. I says, yeah, I okayed it because it was -- coming in at three o'clock and working ‘til seven didn’t bother me but now if I’m going to be here at ten in the morning and hang around the whole day that’s not enough money. So he says, well, I can’t go any more (than that) right now. So one of the engineers in charge there said, Stan, look, I don’t know what your plans are for the future, but if you went to college and you tried to get a job as an engineer or learn an engineering course, you’d go to school for like three or four years, you wouldn’t make any money, and you wouldn’t have a job when you got out. Here you’ve got a job. You’re getting paid to learn as well. And he says the chances are, being that you do everything here you’ll be a better engineer for it.

FREMER: Yeah, the practice.

ROSS: Don’t quit. Give it a few months. Try it.

FREMER: Good advice.

ROSS: Good ad – great advice because I was doing things with disks, I have to laugh; I edited disks. I went from disk to disk to a third disk. I did commercials for Warner Brothers. They did promotionals, radio commercials for them.

FREMER: And that’s what you started doing?

ROSS: Yeah, and I did the first musical jingle in town: “Eastern Columbia, Broadway at ninth, Eastern Columbia, Broadway at ninth, see the big clock atop your department store Eastern Columbia, Broadway at ninth.”

ROSS: And this was (one of) the first musical jingles and I cut it with the Sportsmen Quartet. They were well known at the time from The Jack Benny radio and television program. Benny would say “Hey fellas?” And they would sing the Lucky Strike jingle

FREMER: So you were given good responsibility right away?

ROSS: Well, by the end of the year I was the number one engineer. One of the guys had quit so I was the top engineer and I had a friend of mine I hired, Dick Burns, as my second engineer.

ROSS: Dick Burns was my – we became very – to this day we’re friends.

FREMER: What was Gottschalk doing? He was loafing and letting you work for $28 a week?

ROSS: He was 58 years old and he was busy going out fishing.

FREMER: Oh. So he left – you were in charge.

ROSS: Well, this guy Miller Ennis was in charge, and then all of a sudden about four or five months after I was working there Miller had decided it’s time for him to leave.

FREMER: Wow. But no big stuff was happening there at that point. It was just stuff.

ROSS: Yeah. I cut a gold record there in 1947, a record called “Deck of Cards” by a country singer called T. Tex Tyler.

FREMER: T. Tex Tyler?

ROSS: Big superstar. Big.

FREMER: And why was he coming in to the little studio where you were working?

ROSS: Four Star Records was the name of the label Tyler was on. They recorded at Electro-vox. And when they came in we cut a record called “Deck of Cards” where we used the cards as a bible and Wink Martindale did it in 1957 and also had a hit with “Deck of Cards.”

FREMER: Wink Martindale!

ROSS: Wink Martindale.

FREMER: Same song?

ROSS: Right. And he did the same thing using the deck of cards as a bible and analyzing each picture card and each – really all the suits and all. Unbelievable, this is what the guy does.

FREMER: So you combined gambling and religion.

ROSS: That’s right.

FREMER: Like Bill Bennett? [LAUGHTER] Okay. So this turned into Gold Star or this was --

ROSS: No, this had nothing to do with Gold Star, this is Stan Ross working for Gottschalk at Electro-vox. Not in business any longer.

FREMER: Right. How many studios are? Okay, so now from there what happened?

ROSS: Well, from there I wanted a raise. I’m getting married I needed more money. So he gave me a raise, I got $38. I said no, no, no. I need fifty dollars at least to live on. Oh, no, no, no, I’ll go $45. I say I need fifty. No, I’ll go $45. I said all right, so I took the $45 and I got very disgusted and I decided to go, and I had a friend of mine, Dave Gold, who was an electronics man. In those days we didn’t call it electronics. When he was a kid he fixed radios. He fixed phonographs. And he built turntables, you know, the things that we’re talking about. So, I got a hold of Dave and Dave says, well, let’s go for ourselves, so we decided to go into our own business and I had an apartment, I had an empty bedroom, and I put all this stuff in the bedroom and we built a tape machine. Dave built all of the electronics used in Gold Star, including the first three consoles that Phil Spector loved. So the joke is, because of five dollars, Gold Star was born.

- Log in or register to post comments