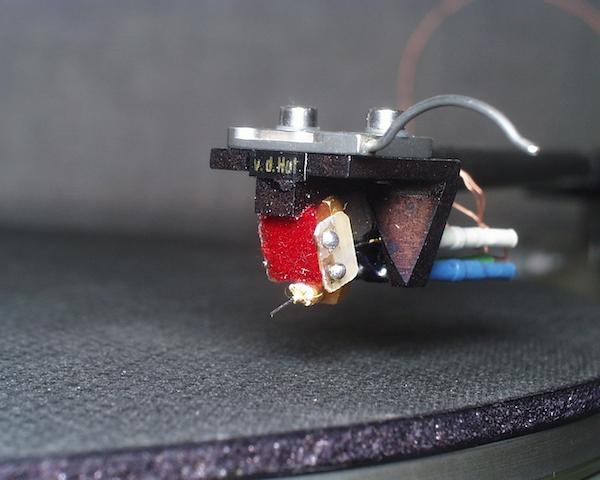

I presume these cartridges sounded good but the Van den Hul looks like a piece of velcro from a red ski anorak got stuck on its front and the Lyra had some quick fiberglass roadside repair done to its underneath.

Analog Corner #116

Shures, Grasshoppers, Dorians, & the Mighty Whest

On November 17, 2004, Shure Brothers announced the discontinuation of its legendary V15VxMR moving-magnet phono cartridge, bringing to a close 40 years of V15 cartridges, beginning with the original V15, introduced in 1964 at the then-outrageous price of $62.50.

For those of you too young to remember, cartridges back then were, for the most part, 1¢ giveaways, as in “Buy a Garrard Type A and get the base, dustcover, and cartridge free!” Grado made a Tri-Tracer cartridge that sold for the insane price of $79.95—but Shure was the big guy on the block, and the introduction of the hand-built, individually tested V15, with its biradial elliptical stylus, was a major event that signaled the maturation of the cartridge market and the supremacy of the stereo vinyl LP. First-time listeners will never forget what they heard.

Shure’s ad in the hi-fi press was headlined “Hobson’s Choice? Never Again.” Finally, the choice of cartridge was too important to be left up to the butler, or the dweeb in horn-rimmed glasses at your local Lafayette Radio store. Plebes and students were left with Shure’s trusty M7/N21D, which cost about $20. Those with a few more bucks to spend could get the M-55E, which itself went on to become a classic of sorts.

Over the years, the V15 was regularly upgraded: to the V15 Type II (1966), V15 Type II Improved (1970), V15 Type III (1973, laminated pole piece, flat response, 25% reduction of effective stylus mass), V15 Type IV (1977, viscous damper, hyperelliptical nude stylus), V15 Type V (1982), V15 Type V-MR (1983, Micro-Ridge stylus), and, finally, the V15VxMR (1997), which was one of the runners-up for “Analog Source of the Year” for Stereophile’s 1997 “Products of the Year” (December 1997, Vol.20 No.12).

According to Shure, the V15VxMR had to be discontinued because of the “scarcity of exotic materials essential in the manufacturing of the VN5xMR stylus.” I assume that the main exotic material is beryllium, from which the VN5xMR’s Microwall/Be cantilever is fashioned. Shure says that in order to maintain its policy of keeping a five-year stock of stylus replacements on hand, it must stop making the cartridges immediately. But for the time being, there are ample stocks of V15VxMRs at vendors, and there will be plenty of stylus backups for the foreseeable future. If you’ve ever wanted to own a classic, now’s the time to act.

van den Hul Grasshopper Condor Gold phono cartridge

Dutch MC cartridge manufacturer van den Hul has a new US importer-distributor, Odyssey Audio, a division of veteran audio importer-manufacturer Klaus Bunge’s Odyssey Designs AV, which also imports Symphonic Line products from Germany and manufactures the Odyssey line of electronics in America and Canada.

The agreement is new enough that, as this was being written, there was nothing about it on www.odysseyaudio.com or www.vandenhul.com—but Bunge did send me a vdH Grasshopper Condor Gold to audition. It’s my first Grasshopper, and only the second vdH cartridge I’ve heard at home; the first was the ultratweaky but oh-so-fast and resolving Black Beauty Colibri ($6000).

Bunge will be selling the cartridges directly for the most part, which is one reason the vdHs will be considerably cheaper than they were when imported by George Stanwick’s Stanalog Audio Imports. Bunge didn’t yet have a complete price list, but the Grasshopper Condor Gold sells for $3000—expensive, though not for a ’Hopper. (The Grasshopper IV, which Jonathan Scull reviewed in the July 1995 Stereophile, with a followup on the IV GLA in May 1999, cost $5000.)

The Condor Gold is part of a line of Grasshopper cartridges crossbred from the Frog and Colibri lines. As is A.J. van den Hul’s habit, it’s available custom-built for the end user’s particular needs, within each of four basic models with outputs that range from 0.25 to 0.55mV. Within each model are yet more variations that I won’t get into here for fear of putting you to sleep.

I received a Grasshopper Condor Gold XGP-MO. Decrypted, those last five initials stand for Cross (X)-shaped modulator, matched crystal Gold coil wire, Plastic mounting platform, and Medium Output (0.35mV). The Condor is a “nude” design, which means it has less mass and that its various parts resonate less, but the long, exposed cantilever increases the odds of disaster: cleaning persons with Swiffers, keep your distance!

A strong magnet allows the design to jettison the front pole piece, which is why the coils and former are so easily seen. All versions use vdH’s 1S stylus, a line-contact design measuring 2µm by 85µm. (A.J. van den Hul invented and holds the patent on the line-contact stylus.) More information on the cartridge can be found on vdH’s website, so I’ll spare you the excruciating details of how I set up the cartridge and of its interface with my phono preamp. I will tell you that it’s a light tracker designed for tonearms of 12–20gm mass, and that its recommended tracking force is 1.35–1.5gm. I liked it best at 1.4gm on Immedia’s RPM-2 unipivot tonearm.

Out of the box, the Condor Gold was not at all like the ultra-light, ultra-low-output vdH Colibri, which I reviewed in the August 2000 Stereophile (Vol.23 No.8). (The Colibri’s output was a minuscule 0.175mV at 5cm/s modulation velocity—or, by the more commonly used standard of the JVC test record, an even tinier 0.1mV! The Condor erased my aural memory of the Colibri’s razor-sharp transients with an immediately addictive top-to-bottom smoothness with no sense of loss of transient detail, overall resolution, or spaciousness. In fact, the Condor’s ability to re-create a natural acoustic space was, in my experience, second to none. Usually it takes some brightness to generate space, but the ’Hopper Condor did it while remaining almost mellow—a rare feat. Your favorite Carnegie Hall concert recordings will leave you semiparalyzed with awe, especially if you’ve actually been to Carnegie.

The Colibri I reviewed was a jaw-dropper, but hyper-real compared to live music. The Condor’s tonal balance was far more natural, striking just the right balance of detail, air, transient snap, and harmonic development. Wood sounded like wood. Strings had that special silky yet piercingly focused translucence you hear live. Acoustic bass was lithely, richly delineated, with a nice balance of string and acoustic body.

The Condor’s spatial presentation was remarkably three-dimensional, in terms of both image specificity and soundstaging. Individual images were portrayed with satisfying and convincing solidity, weight, and dimensionality, with no hint of artificiality or mechanical aftertaste. The definition of edges was just right: image boundaries were not overdefined, which can lead to “etchiness,” nor were they softened and obscured, which often leads to sonic boredom and an inability to clearly “see” the aural picture. If the Condor erred in any direction, it was toward smoothness, but only slightly. That tendency was more than easily compensated for by its superb resolution, ultraquiet backgrounds, and a soothing, calming presentation that was still convincingly realistic.

I pulled out an original RCA Living Stereo LP of Artur Rubinstein, Fritz Reiner, and the Chicago Symphony’s steroidally dramatic performance of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto 2 (RCA LSC-2068). I’d had a reality check at Avery Fisher Hall only the night before, and the Condor’s recorded presentation was remarkably consistent with what I heard then. “Live” usually sounds far darker and softer than most recorded presentations, even from the center of row 20, where I’m fortunate enough to sit. The Condor offered the “live” kind of honest tonal balance—neither hyper to the point of “bright” nor soft to the point of “overripe.”

More important than the sonic particulars was the feeling imparted by the recorded presentation with the Condor. The music felt like what live acoustic music feels like: a combination of presence and detail, plus a liquid ease that’s difficult for recordings to achieve. Still, as A.J. van den Hul says on his website, the XGP-MO version of the Grasshopper Condor Gold is “most suitable for classical music” and, by extension, acoustic jazz and folk, all three of which it delivered with almost hypnotic grace and flow. The Condor’s suppression of vinyl surface noise was also notable.

More raucous but extremely well-recorded music, such as the Clash’s London Calling (UK pressing), revealed the Condor Gold XGP-MO’s somewhat polite and gentlemanly nature, but with the loss of some needed grit. No big surprise—it’s how A.J. van den Hul called it, and I was running the cartridge wide open into 47k ohms, not with the suggested “ideal” loading of 200 ohms. Still, depending on the rest of your system—if it’s already soft, this cartridge might take it under the edge—the Condor, as configured, may still be an ideal all-around choice. And if it isn’t, vdH can tailor it to your tastes and needs.

I loved the van den Hul Grasshopper Condor Gold XGP-MO for all sorts of music. With my double-tonearm setup and the multiple-input Manley Steelhead phono preamp, I can have a tougher customer ready to rock with the rotation of a dial. In fact, I did: Lyra’s new Dorian cartridge was ready to go on the Graham 2.2 arm.

Lyra’s new “budget-priced” Dorian phono cartridge

I told him that Lyra’s previous $2000 cartridge had been the Clavis D.C., that the Helikon was a totally new design using high-tech construction techniques unique to Lyra, and that if the Lyra folks had been in their right minds, they’d have priced the Helikon at $3000 and, given its sonic performance and build quality, it would still have been a good deal. My final recommendation to him: “You already have the $3000 cartridge you love, and you got it for $2000. Now buy $1000 worth of records and enjoy them!”

Did I really recommend that a manufacturer charge a higher price for an already expensive cartridge? Yes. Unfortunately, many audiophiles are too price-conscious. They think that a $3000 cartridge must, by definition, be better than a $2000 one. It ain’t necessarily so. For instance, I’d put the $750 Sumiko Blackbird’s overall sonic performance, and especially its ability to deliver solid musical performance (if not the last word in resolution), up against almost any cartridge at any price. But manufacturers who try to do consumers a favor and underprice equipment often pay a penalty in lost sales.

Which brings me to Lyra’s new Dorian. (Lyra is distributed by Immedia, www.immediasound.com.) It uses the same rigid, low-resonance construction as the higher-priced Lyras (though on a smaller scale)—the motor is integral to the body instead of being simply attached to it. This requires extremely sophisticated machining, according to Lyra designer Jonathan Carr. The cantilever is a relatively short, rigid boron rod, to which is attached a Micro-Ridge line-contact stylus. The Dorian’s output is a healthy 0.6mV—relatively high for a low-output moving-coil cartridge. The compliance is moderate to low, with a recommended tracking force of 1.8–2gm. The price is $795.

Putting the $795 Lyra Dorian up against the $3000 van den Hul Grasshopper Condor Gold XGP-MO is unfair, but I did make the comparison before switching the vdH out for the Helikon. The Dorian’s sound picture was more compact in every dimension, and couldn’t begin to compete with the vdH’s ability to re-create the natural acoustic behind the main event. But the Dorian had its own considerable strengths, and they were the same ones shared by every cartridge in the Lyra line: superb overall transparency and image focus, noteworthy resolution of low-level detail, transient clarity and speed, and taut rhythm’n’pace. If the vdH Condor Gold is about the stick hitting the cymbal, the Dorian and its Lyra brethren are more about the cymbal itself and its resulting shimmer and ring. If the Condor is about chest cavity and body, the Dorian is about the vocal cords. You get the idea.

While the Condor is a much better cartridge overall, it provides a totally different presentation—and there were some things the Dorian did better. Superbly recorded cymbals, such as those on The Modern Jazz Quartet at Music Inn (Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab MFSL 1-228) had a more convincing metallic ring. Milt Jackson’s vibraphone had more of a bell tone compared to the vdH’s portrayal, which, while more complex, tended more toward the sound of the marimba. Despite the extra coil turns needed to increase the Dorian’s output to a more preamp-friendly 0.6mV output, its resolution of fine low-level detail was impressive by any standard. The Dorian won’t change the minds of those who don’t like Lyra’s “house sound,” but it’s a boon for Helikon lovers on a budget: In terms of sound and sophistication of design, the Dorian will get you close to where you want to go for less than half the price. I never did get to hear Lyra’s Argo ($1200), which, like the Dorian, can be thought of as a less sophisticated Helikon. As with loudspeakers, there seem to be as many different cartridge presentations as there are ears to hear them.

The Dorian’s transparency, transient speed, rhythmic solidity, resolution of low-level detail, and taut, well-extended bottom end brought an overall balance and musical excitement that I’ve yet to hear from any cartridge competing at this price. Many fine MC cartridges are available for around $800. The Shelter 501 Mk.II that I wrote about last month ($850) has a more magical midrange, but it can’t match the Lyra Dorian’s transient attack and clarity or its taut, crisp bottom end. Between the two of them, they cover a lot of sonic ground in high style for under $900.

The Lyra Dorian is also available in a mono version so new its price has yet to be determined. I’ve got one here, but didn’t get a chance to listen to it in time for this month’s column. I’ll get to it in January, after my return from the Consumer Electronics Show.

Whest PhonoStage .20 + MsU .20 phono preamplifier

The PhonoStage .20 + MsU .20, designed and built in the UK (www.whestaudio.co.uk), consists of two compact, attractively finished, nonferrous boxes of extruded aluminum—one containing the MsU .20 power supply, the other the PS .20 phono preamp and equalizer—connected via an umbilical with multipin terminations. The multiple regulated power supply has a custom transformer and 300 times the current capabilities required by the phono stage, according to designer James Henriot, who feels that the extra headroom is audibly beneficial.

The dual-mono PS .20 features ultra-low-noise, multiregulation circuits that are claimed to allow the use of the lowest-output moving-coil cartridges without risk of noise. The input stage is claimed to have ultrawide bandwidth of 1Hz–130kHz, ±0.05dB, for reproduction up to 50kHz, which Henriot claims modern cutting heads and matrix processing are capable of etching into LP grooves. "Useable" playback response, according to the designer, goes down to 16Hz, which makes sense since the last thing you want to do is amplify rumble, warp/wow and the arm/cartridge system's resonant frequency!" The RIAA filter, also designed to express frequencies up to 50kHz, is said to be accurate to ±0.2dB.

A discrete output stage is used instead of an integrated circuit because, among other reasons, Henriot claims that current and headroom are required to accurately reproduce soundstaging, image solidity, and overall speed. The output stage uses discrete devices usually used in the driver stages of modern power amps, and the circuit is claimed to operate at up to 30MHz from ±30V voltage rails. Gains are specified at 40dB (moving-magnet) and 58–72dB (moving-coil), adjustable from inside the PS .20 (according to the designer, but I could find no such adjustment when I opened the case). The noise is specified at –79.5dB/0.04µV (60kHz measured bandwidth), the distortion 0.0063%. Overload is specified at 11mV input, presumably at 1kHz for MC operation, for 15V output. These are outstanding specs.

Resistive loading is adjustable via a pair of RCA jacks on the rear panel. Whest supplies sets of plugs for 47k, 550, 220, 100, and 50 ohms. Custom values can be ordered, and it’s easy to make your own. You switch between MM and MC via a switch mounted on the rear panel.

Go Whest, Old Man!

As with the MM-only Gram Slee GSP Audio Era Gold Mk.V, which I reviewed in my January 2004 column, from the moment I began listening to the Whest PS .20 + MsU .20 I knew I was hearing something that was truly special at any price, let alone for $2495. The Whest was ultraquiet, but beyond what wasn’t there, what was there immediately reminded me in many ways of both the Boulder 2008 and the fabled Mares 2.0. I’m not suggesting the Whest is as good as either of those, but it belongs at the same table. In head-to-head comparisons with my reference Manley Steelhead phono preamp and the vdH Condor, Lyra Dorian and Titan, and Brinkmann EMT cartridges, the Whest seemed to equal the $7300 Manley’s dynamic expression, image solidity, soundstaging certainty and size, and especially its ease and liquidity—amazing, considering the price difference and the Whest’s solid-state circuitry and utter lack of step-up transformer.

The top-end extension was fully realized without etch, glare, grain, or artifice of any kind, and there was no transient price to pay in terms of perceived softness or roundness. Strings had just the right balance of velvety sheen and grit, brass had bite and proper warmth, and voices were smooth, complex, and well balanced. Switching between the Manley and the Whest told me that the $2495 phono preamp could deliver the full expression of any of the top-shelf cartridges I tried. While it lacked the Steelhead’s flexibility, it offered more than enough for most end users, and it was quieter—not that the Steelhead is noisy. Music just poured forth from the Whest with a natural vibrance and honesty that are rare at any price—and, I’d thought, impossible for $2495.

The Whest “slowed time,” much as the Boulder and Mares do, though not quite as dramatically. But its bottom-end extension and rhythmic thrust were the equal of any phono preamp I’ve heard—except for the Boulder. It carved 3D images as well as any phono preamp save the Boulder and Mares, and had a relaxing quality that put my mind at ease, and is rare and special in any piece of audio gear. It was liquid without being soft, yet was also properly edgy and “grippy” without being too sharply etched.

If I’m raving now—as I hope I rarely do in this column, if ever—it’s because the Whest is so unlikely: physically small, inexpensive for what it does, and the product of the imagination and skill of a designer I’d never heard of. I had no expectations when I first plugged it in, and I’ve been listening to it using the extremely revealing Verity Audio Sarastro loudspeakers ($30,000/pair), which are equipped with Raven ribbon tweeters. I plan on revisiting the Whest after CES because I need to spend more time than I’ve had to be sure that I’m not going over the deep end here.

I don’t think I am. For now, the $2495 Whest PS .20 + MsU .20 is in my list of top 10 phono preamps. If you need more bloom and a richer picture, you can go to the superb-sounding BAT VKP-10 or the Zanden 1200 or the Conrad-Johnson Premier 15—all of which use tubes. The Manley Steelhead with stock tubes never sounded rich or bloomy to me, which is one reason I like it so much. The Whest sounded remarkably similar to the stock Steelhead, and costs a lot less.

Sorry I didn’t cover what I promised last time; the Whest PS .20 + MsU .20 got the best of me.

- Log in or register to post comments

It is amazing to me that more than 14 years can go by and some things change a lot and some things don't. I had the pleasure of meeting A.J. van den Hul at Axpona this April and bought one of his Crimson Stradivarius cartridges. I had not planned on buying a VdH. I am more of an Ortofon fan, thinking that a (relatively) huge company like Ortofon can apply it's economies of scale and massive R+D to produce a better produce for the money than one-off creatures of a single man working over a microscope. But then I laid eyes on Mr. van den Hul who was listening raptly with his eyes closed to a classical music record in the room he co-sponsored with Finest Fidelity featuring Acoustic Arts electronics and Magico speakers. The room was practically empty but Randy from FF, Mr. vdH and me. Mr. van den Hul looked so content. The music was coming from a vintage Garrard 301 and his $12,000 Colibri Master Signature cartridge. A new to me paradigm came into focus in my brain-there are masters of craft out there like the fabled Ken Shindo who instead of crafting electronics like Shindo-san craft amazing phono cartridges-like A.J. van den Hul, and they too are worthy of consideration despite the high prices associated with the product. 14 years later A.J. van den Hul appears at peace with his age and accomplishments-it meant nothing to him that the room was temporarily empty and that the many enthusiasts in the crowded hall just outside the door either did not recognize him or did not care. Not that I have had two months to enjoy my Crimson on my Garrard 301 with Reed 3P, and one month to enjoy it after having Brian Walsh of TTsetup dial it in with precision, Mr. van den Hul is a hero of mine.

Great article on the travels of Shure cartridges. I happen to have a Shure V15 Type V cartridge in desperate need of a stylus. Michael, any suggestions where to find one at this tlme? Always loved that cartridge. Thanks.

Mike, you are sure correct about the sound quality of these units, however, I had 2 of these units and both had the same problem, popping and funny buzzing noises, I contacted James and he couldn't even be bothered to solve the problem, he suggested one of his PS 30rdt units, which had the cheapest plastic feet I have ever seen held on with rusty screws, it sounded nowhere near as good as the Whest .20 + MsU .20I, in the end I sold both the Whest .20 units on ebay explaining they were faulty and the buyer told me they heard the same noises. "Beware of nice talking people.