Analog Corner #23

(Originally published in Stereophile, June 12th, 1997)

Eddie Kramer stopped by yesterday to play me the new MCA Jimi Hendrix LPs and CDs, which will be in the stores by the time you read this. Was it a kick having Kramer, who engineered all of the Hendrix recordings (and some Beatles, Stones, and Traffic too) sitting in my "sweet spot''? Duh! It was also a bit nerve-wracking. He knows how these things are supposed to sound. I only know what I like.

So before he arrived I cleaned my connections and checked all the setup parameters on the turntable. When I was satisfied everything was dialed in, I demagnetized the Transfiguration Temper, ultrasonically cleaned the stylus, and left the 'table spinning to warm up the bearing grease. I wuz ready.

KoB revisited

As I awaited Kramer, UPS delivered a test pressing of Classic's reissue of Miles Davis's Kind of Blue. Wow! While some may quibble with Bernie Grundman's mastering of classical music, no one doubts that his experienced ear for jazz is probably the best in the business.

Here the job was easy: He set up the three-track master tape and let it play—no equalization was necessary. For the first time, Grundman used a tube cutting system originally part of Contemporary Records' chain, borrowed from John Koenig. The results are truly spectacular—an effortlessly natural overall presentation that offers clarity, focus, and timbral richness superior to the "six-eye." The two-LP set gives you the original Kind of Blue on one record (which means that side one is a quarter-tone fast), and a second disc with side one at the correct speed and a 45rpm version of an alternate take of "Flamenco Sketches" on the other side.

Meanwhile, Sony's just issued its third or fourth CD attempt at Kind of Blue (CK 64935), and this time they've nailed it too, using a tubed playback deck—a refurbished three-track vintage Presto machine—and 20-bit Super Bit Mapping. Grundman's Studer has solid-state electronics. Guess what? While the LP sounds harmonically richer and has better instrumental focus and a greater sense of transparency and depth, the CD has more "air" around instruments and sounds a bit more open—as you'd expect tube sound to be. In a real-time A/B it's close, folks, though to my ears the LP is still more "involving" and nuanced in the ways that analog is. But, at $10.99 or whatever it costs, the CD is the real digital deal—don't leave home without it.

Back to Hendrix

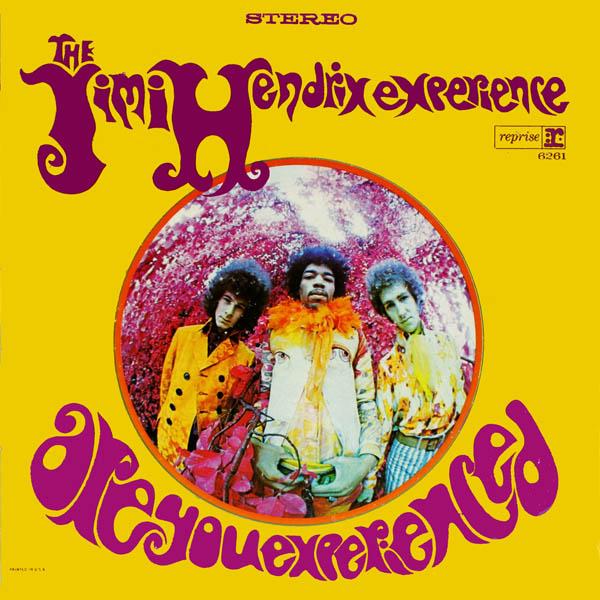

Kramer showed up with MCA's 180-gram "Heavy Vinyl" test pressings and CD-Rs of the first four Hendrix reissues: Are You Experienced on two LPs—the original American running order plus the mono singles mastered from the original mixes; Axis: Bold as Love on one disc; Electric Ladyland on two LPs; and First Rays of the New Rising Sun—part of which became The Cry of Love—also on two discs. First Rays is the album as Hendrix intended.

In the limited time we had we compared original American and British pressings, Japanese pressings, German pressings, and the older MCA CDs—the ones with the stamps you lick but nothing happens—with the new CDs and vinyl, and we compared the new vinyl with the new CDs. Only The Ultimate Experience (an early HDCD-encoded European release) didn't make it to the Audio Alchemy DDS•Pro transport. I need to spend a lot more time listening before I make any final judgments, but I can tell you that the new LPs and CDs are BIG—really BIG-sounding, with vicious, deep, solid bass, rich midbass, and master-tape–like extended top end.

There's a big Hendrix controversy regarding master tapes or not master tapes. Kramer and Hendrix biographer and archivist John McDermott claim that what were used previously were mostly not masters. Joe Gastwirt, who worked on the previous issues, claims that they were. That's a subject best discussed at another time and in another venue, after some interviews and extensive listening.

However, Gastwirt's recent slamming of Kramer in the pages of ICE (Footnote 1) was a tactical blunder, in my opinion, that tarnishes Gastwirt, not Kramer. Hey, anyone whose name is on that steaming pile of sonic excrement called Kiss the Sky should choose his words very carefully. But I'm not going to take sides until I spend time listening to the finished products, past and present.

But let me tell you about the LPs: The lacquers were cut at Sterling Sound by George Marino from a 16-bit digital source—as much as Kramer, an analog kind of guy, didn't want to. Because the tunes were recorded over time and under varying conditions, the head azimuth shifts from track to track. There was no way to play the master and cut a lacquer without running into high-frequency rolloff problems, according the Kramer. So the heads on the Ampex ATR deck were aligned for each track, with the signal going to Pultec and other tubed analog EQs for minor (1dB max) touch-up, and then to a George Massenburg 20-bit A/D converter, the output of which was fed into a Neve digital console for any kind of minor touch-up. The digital data were stored on a Sonic Solutions system. Almost no compression was used for either the LP or CD versions.

I spoke with Marino, who told me that the ATR machine was chosen for its sound. Since this sample did not come equipped with a preview head, cutting all-analog would have been impossible even had the tapes been consistent enough to allow it. He also told me the Neve's D/A converter was used to convert the signal back to analog for the lacquer cuts.

The 180gm LPs were pressed at MCA's plant in Gloversville, New York. Kramer and McDermott, aware of the "nonfill" problems on the first batch of MCA Heavy Vinyl, were given carte blanche by MCA to get the pressings perfect, and they busted hump to get them that way. We'll wait for the final vinyl before announcing the sonic verdict, but the test pressings I heard were very quiet and nicely finished.

Based on what I heard, timbrally the test pressings and CD-Rs track perfectly. The CDs win in dynamics, but not by much. The LPs win in terms of inner detail, midrange purity, and depth, the biggest difference being on Axis: Bold As Love; "Castles Made of Sand," at least, sounded much better on vinyl.

It might have been interesting to hear what Bernie Grundman or Stan Ricker or Doug Sax or MoFi's Ken Lee could have done with the tapes in the analog domain, despite the azimuth shifts, but that's not going to happen—I think us vinyl guys and gals should show MCA that vinyl's viable by supporting these releases. Eddie ("Digital Sucks'') Kramer is happy with the results, so who are we to complain?

I wouldn't let Kramer leave without playing him the German pressing of "Baby You're A Rich Man," which he'd engineered at Olympic Studios. If you haven't heard that German LP, you haven't heard Magical Mystery Tour. Kramer wasn't aware that the American versions of MMT on LP, including MoFi's, featured many cuts that were originally recorded in stereo—like "Baby You're A Rich Man''—in badly reprocessed-for-stereo mono. Why? Some folks at Capitol back then didn't really give a shit. Isn't that special?

Temptin' Temptations

My local public library announces a "friends of the public library" book sale. They advertise for residents to donate their used books, CDs, and videos. Something missing here, right? I call the woman in charge and tell her that records are a good draw, which of course is a big shock to her even though she still plays hers. I convince her to add the groovy ones to the announcement, which she does. "And you can sort them when they show up!" she announces. Talk about putting the fox in charge of the hen house (slurp slurp)!

The monday before the sale, I arrive at the library basement. I'm greeted by 5'-high piles of boxes and plastic bags, mostly filled with books. The records are the usual suspects: Streisand, Michael Feinstein, The Carmen Cavallero Story (it must have been the Thriller of the '50s), and the others you always find and never want—even for a quarter.

But digging through the rubble I come upon four taped-up, record-sized boxes of crisp cardboard, bearing the name of a local moving and storage company. I can smell the quality vinyl stacked up inside. I can taste the dust. My heart races as I feverishly slit the tape on the first box. I rip open the flaps and there it is—the mother lode, the vinyl schnorrer's wet dream. An entire box of mint—I mean unplayed-looking—MoFis, Nautiluses, MasterSounds, and Japanese pressings. I'm not kidding you. The Doors, Aja, Ziggy Stardust, Fleetwood Mac, Abbey Road—I'll spare you the whole list—and Japanese pressings of Dire Straights, Tom Petty, Alan Parsons, Pink Floyd, Steely Dan, and more—more than 30 pristine collectibles.

"What could be in the other boxes...?" I think. Well, no more half-speeds, but dozens and dozens of machine-cleaned, rice-paper–sleeved rock and jazz albums from the '60s, '70s, and '80s—and the Shure V-15 Type V test record. This was some audiophile's collection. Either he died or ended up following Audio editor Michael Riggs into digital hell—almost the same thing.

You know, I could have said "a buck a piece and I'm taking these 50, here's $50," and no one at the library would have been the wiser. But I didn't. This was for charity. Plus, I already had clean copies of all of them, so why be a vinyl pig? Instead, I put them out for $15 each—a sum no one at the library thought we'd ever get—and the rest for a buck, and by the first afternoon of the sale all the collectibles and over two thirds of the rest had been sold. I did snare about 50 good records for a buck each, though. So I was rewarded, the library made money, and a bunch of record collectors—many of whom were my friends—went home smiling.

Sorry, Sold Out

Now that Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs has exited the LP market, "investors" are buying multiple copies of what's left, for future speculative value. Grave robbing, if you ask me. Where were these people when the label needed encouragement to continue? Meanwhile, according to MoFi's latest catalog, the following LPs are sold out: We're All Together Again for the First Time (Brubeck and Desmond), Derek and the Dominoes In Concert, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, Getz/Gilberto, Body and Soul (Billie Holiday), Gerry Mulligan Meets Ben Webster, Nevermind (Nirvana), A Day at the Races (Queen), Reckoning (R.E.M.), and Muddy Waters Folk Singer. I'll bet there are copies of some of those lurking at dealers. The Bob Marley albums are still in stock, but for how long?

The Stan Ricker Saga—-finally

Last summer's visit to LP pressing house RTI in Camarillo was a real treat for many reasons, not the least of which was a chance to sit down and talk with Stan Ricker, who does the cutting at Chad Kassem's and Don MacInnis's in-house AcousTech mastering facility. [Ricker mastered Stereophile's recent Sonata LP; see March '97, pp.75–89—Ed.] Never a guy to hold back what's on his mind, the pleasantly cantankerous Ricker greeted me one morning at the Alexis Park 1997 WCES venue with "Fremer, you look terrible! You look like you were ridden hard and put away wet!" (I should have been so lucky .)

I laughed—I knew Ricker was just horsing around. [Oy.] Besides, I'd gotten up early that morning to do three miles on a treadmill and was feeling great (Footnote 2). The mastering veteran does rub some folks the wrong way, but I can relate: I find him refreshingly candid.

Ricker is one of those names well-known to long-time vinyl fanatics. He cut audiophile discs at JVC's fabled Los Angeles facility in the '70s, and went on to greater glories with the first wave of Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab half-speed–mastered LPs. (He also plays stand-up bass and tuba.) As a child the Marblehead, Massachusetts native moved to Highland Park, Illinois, near Chicago. As soon as he was old enough he began to visit Allied Radio, "back when it was at 833 West Jackson Boulevard, which was the back end of a shoe store. That's where I first heard Electrovoice SP-12s in an Aristocrat corner enclosure actually get 32-cycle low C. That was cool; that was something you normally don't hear," Ricker recalled, reliving the experience as he spoke.

Ricker lacked formal training in this field; he was "a hobbyist" who had built a console with three Webster, Chicago turntables fitted with General Electric "variable reluctance" cartridges. Ricker remembers mounting three 15" Jensen H-510 loudspeakers in a closet door in his bedroom. He modified the drivers by adding cloth suspensions fashioned by his mother, a seamstress. He still has one; it still works, he told me.

Ricker cut his first record when he was Century Franchise Recording Associate in Lawrence, Kansas in the late '60s. He sent the tapes he was making—he thought they sounded pretty good—to the Keysor-Century pressing plant. How were the LPs he was sent back? "I don't mean to be disrespectful, but they were goddawful records. Jack Renner [co-owner of Telarc] was going through the same thing."

Keysor-Century franchisees recorded high school and college bands around the country. The tapes were sent to the company's Saugus, California headquarters, where they were mastered, plated, and pressed into those "goddawful" records. Each production sold 100 to 200 copies. The company is still around, supplying vinyl to pressing plants like RTI.

Ricker complained so much about the poor-quality records Keysor was producing from his tapes that the company hired him. But not before he'd humiliated them by sending one of his tapes to famed disc masterer George Piros, who cut all of the original Mercury Living Presence records. Every record with Piros's name on it sounded good, Ricker told me, so it seemed like a logical idea. Imagine Piros cutting Byron Janis's performance of Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto 3 in the morning, and the University of Kans as Orchestra in the afternoon!

But that's just what happened. From there, the lacquer went out to Keysor like all the others. When K-C's QC people heard the test pressing, Ricker told me, they said, "Holy cow! What is this?"

Ricker and Piros went on to become good friends. Ricker told me that while Piros enjoyed cutting "Freddie Fennell records," he didn't much go for the loud, screaming stuff he had to cut later at Atlantic Records.

In 1969 Ricker picked up his things and moved to Saugus to oversee quality control for Keysor-Century, where he found that most of the problems were related to disc cutting. "The first time I walked into a disc-cutting room, I said, 'By God, that's what I want to do!' It's your last chance to apply any musical sensitivity."

At Keysor, Ricker found himself in one of the few places that did everything from manufacturing (and constantly inventing new formulations of) vinyl to disc cutting, plating, and pressing—even printing labels and fabricating jackets on four-color presses. That was when vinyl was getting really bad, if you're old enough to remember.

Ricker taught himself to cut records by watching how it was done at Keysor, though what was happening there was not exactly kosher. He recounted how the company had bought the first two Neumann computer lathes sold in the US. (Previously they'd used Scullys with Westrex cutter heads.) They bought the lathes but not the Neumann cutter-amp package or the Neumann cutter heads. They kept the big, heavy Westrex cutting heads, which required extensive modification. They had no variable depth for cutting stereo, so to prevent vertical overmodulation they used a device called a Compatilizer, which would let you choose the crossover frequency where you'd sum left- and right-channel bass to mono. They'd set the device at 700Hz—an octave and a half above middle C! "Everything was gone—the spaciousness was gone," says Ricker.

Ricker left Keysor in 1970 to work for Glen Glancy at United Sound Recorders in Burbank, which had a pre-computer Neumann lathe. The company was cutting lacquers for Keysor franchisees who wanted better quality than they were getting from the home office. There was so much work that Glancy needed a second engineer. In 1972 he gave Ricker the run of the place, telling him, "Here's a cutting room, here's a bunch of tapes—go in there, have a ball, make your mistakes, and do your thing."

Later, Keysor hired Ricker back to run the recording facility and cut records. By then Keysor had sprung for the rest of the Neumann gear. While there Ricker cut a 15-LP set for the US Navy called Heritage of the March, which, Frederick Fennell later told Ricker, had become a much-sought collector's item. Ricker's cutting star was on the rise.

From there Ricker moved over to Location Recorders for a few years, and then on to the cutting facility that JVC had opened in Los Angeles to cut CD-4 quadraphonic records (of all things!), since the company had signed onto and was sponsoring the ill-fated format.

For those of you too young to remember, there were three main competing quad formats: SQ (Columbia Records), QS (Sansui), and JVC's CD-4. CD-4 LPs were mastered at half-speed because the format required a 30kHz carrier frequency to be engraved in each groove wall. You couldn't put 30kHz through a cutter head, of course, but 15kHz you could. This was not the first time half-speed mastering was used, Ricker told me. "Half-speed mastering had been done earlier by London Records—Decca [ffrr], the early Phase-4 recordings—[because] there were no cutter heads available at that time to cut good level on a record with. So when you cut at half speed...it drops the frequency bandwidth an octave, and it requires only one fourth the power to cut the record."

CD-4 didn't take off, and Ricker was sitting there with this superb cutting facility—he had to drum up some business to keep it open. By turning off the FM carrier-band generator and raising the level 6dB, Ricker found he could cut great-sounding LPs. Ironically, one of Ricker's first clients was Brad Miller, of the original Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab—the company that produced sound-effects records, and that today is pushing DTS-encoded, 5.1-channel CDs! Talk about a big circle game!

More than just one man's personal tale, Ricker's chronicle is bound up in the later history of the LP. After Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab, Ricker cut high-quality conventional two-channel lacquers for Telarc. It was Ricker who cut the infamous 1812 Overture with the almost 90º-groove cannon shot—"big-assed displacement," he calls it.

Ricker cut the famous direct-to-disc recordings for the Crystal Clear label by packing up the lathe, loading it into the back of his '59 Ranchero, and hauling it over to the Garden Grove Community Church (now The Reverend Robert Schuller's Crystal Cathedral), where the famous Virgil Fox direct-to-disc records were cut. Fox died shortly thereafter.

Ricker recalls measuring the Ruffati Brothers organ's output at 117dB—one loud organ. That was the first time the dedicated half-speed lathe was used for real-time cutting. Ricker had to borrow a "real-time" RIAA card from RCA's cutting facility, located in the same building at 6363 Sunset Boulevard.

It was at this JVC facility where Ricker began cutting the Mobile Fidelity half-speed–mastered LPs we all know and some love, including The Beatles Box. The original master tapes, securely packed in mu-metal cases and insured by Lloyds of London for a million dollars each, were hand-carried from England. "I was really excited just to have this historical product in my hands," Ricker told me.

I asked Ricker about what sounds like jacked-up treble on the Beatles records. "Some of that stuff I did because Gary Giorgi—who by this time was occupying the position of not only vice president, but was the 'guru' in charge of production—slipped and fell, landed on one of his ears, and damaged his hearing. His high-frequency hearing was way down. It got to the point where I had to send him reference discs of everything I was cutting....He'd phone me back, saying, 'Yeah, sounds pretty nice, but I'd like to add about 6dBs more at 10k.' I told him, I told Brad Miller, and later I told [Mobile Fidelity president] Herb Belkin we should not be doing this—it's not valid. But Gary was calling the shots. I like 'zingy' myself, but [The Beatles] are over-zingy.

"See, Gary didn't understand the interface between the mass of the stylus and playing a lacquer, as opposed to playing a glass-hard JVC pressing. I mean, the groove deformation in playing a lacquer is monstrous. You only get about 50% of the high end you put into it....When you cut, you have to know what kind of vinyl it's going to be pressed on."

Ricker told me that one of the records he cut at the JVC facility for MoFi that he's most proud of is MoFi 008—the John Williams Star Wars/Close Encounters, with Zubin Mehta and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

MoFi offered Ricker a full-time cutting job in about 1979. He took it, but left in 1983 because of family health problems. He went to work for the Navy doing administrative work; he's still there because there's not enough work cutting records. In 1986 Ricker went back to MoFi for a short time, but that "didn't work out," he told me.

When MoFi returned to the LP business a few years ago, Ricker was back at the cutting lathe, though most of the new LPs, including Muddy Waters's Folk Singer, were cut by Ken Lee. Last year, when Chad Kassem and Don MacInnis decided to buy Wilson Audio's cutting system (previously owned by Fidelitone of Los Angeles), they called Ricker. End of story.

Footnote 1: Peter Howard's opportunistic newsletter shamelessly hyped the perfection of CD sound from the getgo, and is appropriately named, given what those "perfect" CDs sounded like.

Footnote 2: You know you're at high-end headquarters when you're the only one in the gym every morning. This is an industry in serious need of getting up off its collective fat butt and doing some exercise! End of sermon.

- Log in or register to post comments